The fatalism by which incom-prehensible death was sanctioned in primeval times has now passed over into utterly comprehensible life. The noonday panic fear in which nature suddenly appeared to humans as an all-encompassing power has found its counterpart in the panic which is ready to break out at any moment today: human beings expect the world, which is without issue, to be set ablaze by a universal power which they themselves are and over which they are powerless.

—Adorno and Horkheimer,

Dialectic of Enlightenment

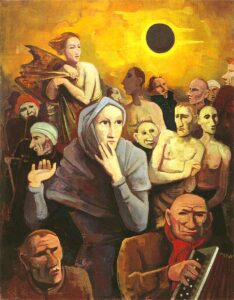

In modernity, “Zero Hour” is an event waiting to happen, as critical theorists from Adorno to Žižek have presciently seen; our experience of the COVID-19 pandemic reconfirms the event as a “noonday panic fear” that structurally recurs. In Germany at 1945, this moment of destruction is conventionally known as Stunde Null, which we may translate as “Zero Hour.” I use the concept of Zero Hour—seen as the punctual moment of political and material destruction that ended Germany’s Totaler Krieg (total war) through unconditional surrender on 8 May 1945—as a metahistorical concept, after the work of narrative and conceptual historiographers. As such, Zero Hour is not simply reducible to its historical date; it has a structural relation to real-time historical unfolding in both narrative and nonnarrative terms. Zero Hour thus did not simply happen; rather, it is a phenomenological moment that took place “as if” it were an actual event, no matter how the particular details of history coincided with it. Psychoanalytic processes of destruction, repetition, and Nachträglichkeit are crucial for the historicity of Zero Hour, as an opening to the Real “that can only be known in its effects.” At the same time, what we term Zero Hour as a historical fact is irreducible to a concept—formed from a complex multiplicity of individual and collective, human and material experiences that only retrospectively condense into the univocal date, 8 May 1945. There is, as well, a unique political content to this historical endgame, a combination of the persistent German commitment to Totaler Krieg after massive defeats that began with Stalingrad, matched by equally persistent Allied demands for total capitulation. Zero Hour is thus a composite historical fact, viewed through an imprecise historical frame, that extends from a series of moments of destruction and liberation that constitute it. As a historical event, Zero Hour is a punctual moment that is not one, depicted and imagined through a series of iconic images of human bodies and urban destruction that took place with military defeat, the liberation of the camps, the destruction of cities, the mass displacement of peoples, occupation by allied armies, and civilian privation throughout Europe. A reduction of human experience to material bare life as a political, cultural, and even existential reference point—and its overcoming—gives Zero Hour a meaning well beyond its narrative origin as null point. My account of Zero Hour is thus not primarily concerned with the narrative it begins for the immediate postwar political or cultural order, but focuses on the moment of the event itself. Zero Hour is a material, not merely a phenomenological, event of destruction that announces a new world order; to locate it, we must work carefully through the combined figural logics and material evidence by which it was experienced and represented.

Notes and links

Text: from “Modernity @ Zero Hour: Anticipatory, Punctual, Retrospective Universals” (work in progress)

Image: Karl Hofer, Schwarzmondnacht—Potsdam, 1944