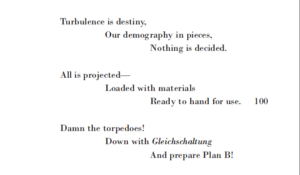

These are the words that conclude “Plan B,” my poem written after the Trump election in 2016. What has transpired since could not have been more like—turbulence has been destiny, our demography is in pieces, and nothing is decided. It is that moment of stoppage—”the stopping / of the battle,” as Charles Olson wrote—that I wanted to get down, as my contribution to radical democracy perhaps. But even the concept of “radical democracy” is not now decided—that is in the nature of a decision—with the spectacle of the “mob” thinking it represents the demos violating “the People’s House,” as we have been told and can see for ourselves. My point is the instability of the moment, but also that of the discourse that represents it or attempts to intervene in it. Is that a good thing for poetry, to record such a moment, or a bad thing for politics, that its confusions may be reproduced?

Something like that occurred at the time of writing, December 2016, when I was asked to participate in a teach-in at Wayne State University (“here comes trouble” can be heard in the background, though muted). In the event, I wanted to perform a brief intervention—a term combining avant-garde and radical tendency—that would stop the moment and in so doing refuse to normalize the election. A politics of “refusing to normalize” had emerged at the time (“Not My President” was its slogan), which ought to have been continuously pursued, from then to now. Such would be a contribution of the avant-garde, of language-centered writing, to the debacle of the election, but it is apparently not possible to not normalize over an extended period of time, even as public discourse has only become more irrational. My second focus was the NS term Gleichschaltung, dating from March–April 1933, when both individuals and institutions “switched over” to a perversion they could scarcely comprehend, while Jews and Roma, communists and queers began to be sent to the camps. Refusing to normalize might keep Gleichschaltung at bay. As it happened, only baby steps in that direction were taken, but they were real.

My presentation was informed by the state of mind I was in when I wrote the poem—channeling Adorno’s Authoritarian Personality and trying to reverse direction by disclosing multiple strands of unreason in the discourse of the event. After an attempt to summarize Adorno’s thesis—that democracy conceals and even reproduces psychological dynamics that prepare a subject to accept undemocratic politics—I attempted to introduce one such a psychological strain into the discourse: Trump’s famous “grab them by the [———]” remark. My point was that those voting for Trump might find that shocking or unacceptable on its own terms but would vote for him nonetheless (just as he could, as he claimed, shoot someone on Fifth Avenue and they would still vote for him). It was not that his constituents believed what he said as a positive claim; rather, it was a placeholder for something else—those “unfulfilled democratic demands” Laclau and Mouffe theorized, but now normalized in a form of perversion. This was a shocking thing for me to say in public as well, and I would not say it again—nor would anyone else; it has become thoroughly euphemized. Is the euphemism its normalization, I wonder? The reaction was immediate, especially from those in the back row who could not get the irony of my speech, and I was virtually chased out of the room by a person who claimed I had “insulted everyone in the room.” That is now part of a larger narrative, but later for that.

“Plan B” is written in an economy of 100+1 stanzas, with the keywords “Plan B,” “Gleichschaltung,” and “normal” or “normalize” appearing every ten stanzas. [. . .] Gleichschaltung as a concept emerged in March/April 1933 in Germany, combining psychological and institutional processes through which political subjectivity “switched over” and was “coordinated” in the fascist state. It influenced Adorno’s notion of “identity thinking” as a combination of reason and terror. The “normalization” of unreason as a form of political subjectivity was what I feared would happen after November 2016, and which the poem contests. [. . .] The precise meaning of “Plan B” is thus hermeneutical and still unfolding; we do not yet know what it will be. [Lana Turner 12]

I had reasons for what I was trying to do; I was being rational in putting forth a discourse of unreason. In so doing I follow in the footsteps of the avant-garde, adapted to later times and modes of address. The question I raise now is the relation of the use of defamiliarization—of “not normalizing”—as a politics. I would say now, given the continuing unfolding of unreason in public discourse that followed the 2016 election, that a mere reversal of normalization is not enough. That guy in the photo with fur hoodie, bare-chested tats, horns, and a six-foot-long spear is not a radical democrat—though neither was the failed intervention at the Capitol a moment of Gleichshaltung, though it could have been had things gone worse. At the same time, I do not agree to any form of symptomatology of the poetic attempt to “not normalize.” I wrote the poem out of necessity and purpose, and it has been true for at least four years. The present moment may be its unveiling, or its necessary end.

Links

Barrett Watten, “Plan B,” Lana Turner 12 (Fall 2020): 109–25; pdf download here.

———. From “Plan B.” Philosopher au present. “Après Trump,” part 6. Ed. Jérôme Lèbre. YouTube.