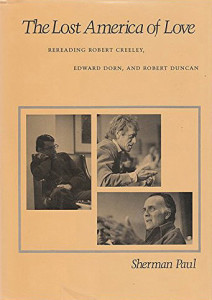

The question of my relation to the New Americans over the long decades since the ’70s has recently come up. In working through my last post, a response to a review that framed my 2016 book with a retelling of the poetic debacle of 1978, I linked to an essay I published in 2000 (per copyright date; it likely appeared in 2001) that was, at the time, my critical and historical assessment of some of its major figures: Robert Creeley, Edward Dorn, and Robert Duncan. Duncan (1988) and Dorn (1999) had already passed, and I do not think I sent the essay to Creeley, with whom I maintained good relations at the time (Creeley died in 2005). Creeley tended to glaze when I sent him offprints of my critical writing, for instance the essay on “poetic vocabulary” that links Jackson Mac Low and BASIC English, to which he wrote a one-word response: “Impressive.” Only later did I find, via a comment Creeley dropped in conversation and a letter in his Selected Letters, that BASIC English had been an influence on his work, after a high school teacher asked to write an essay using its minimal vocabulary.

The events of September 2001 decisively changed the focus of thinking through the poetics of the New Americans onto a more immediate political situation; the broad expanses of time needed for genial conversation on poetry and poetics would be displaced by a militarized discourse of threat, reprisal, and nonexistent WMDs. The essay itself was a kind of swerve, using a request from editor Timothy Murphy for a contribution for a volume of the academic journal Genre to be titled “Desert Island Texts,” with a prompt something like, “what one book would you want to have if stranded on a desert island.” … More