Questions of Unreason in Modern Cultures was the title of my Fall 2018 seminar at Wayne State University (syllabus here). While there were many enabling factors and contexts, this seminar was the initial and primary site of an explosion in my graduate teaching whose consequences I am enmeshed in and that I am still trying to understand. As a rough-and-ready index to the issues at the heart of this explosion, I liken it to another moment on a world-historical scale: the nuclear disaster depicted in the miniseries Chernobyl (dir. Johan Renck, 2019). As the episodes unfold, we begin with the disaster itself—an incomprehensible meltdown that occurs with barely a moment’s notice at 01:23:45 A.M on 26 April 1986. It is only when the pieces of graphite are found strewn around the outside of the reactor building that the truth begins to dawn: the reactor’s core has exploded, an event supposed to be impossible. What follows is the step-by-step effort of the nuclear scientists Legasov and (fictional) Khomyuk to reconstruct and restage what happened in the final episode. The precise timeline of events is the conclusive proof of the relationship between human error (ideology) and nuclear energy (material) that gives the event its world-historical dimension, demanding a “new categorical imperative” of truth telling so that it may never happen again.

My analogy may be a stretch, but I did see Questions of Unreason in Modern Cultures as having its world-historical moment: to comprehend the surge of public unreason since 2016 in the U.S. and elsewhere with the rise of protofascist populisms. It all began with the debacle of a December 2016 teach-in at WSU—where I tried to summarize Theodor W. Adorno et al.’s The Authoritarian Personality in 15 minutes, and spectacularly failed to do so, resulting in all kinds of “projective” responses and very little consensus—but also with the writing of my anti-Trump poem “Plan B.” I saw these as part of a single effort, which continues with my work on Zero Hour and the rise and fall of German fascism, finding similarities and differences in the present moment. This was admittedly an ambitious project: to locate the nuclear core of unreason in protofascist discourse that explains its causes and appeal, and allows it to be read even in popular movements that oppose it.

The Authoritarian Personality was key to my critical account of the rise of protofascisms, seen not as a stable politics (yet) but as an overlap between ideological and psychological elements. As Peter E. Gordon writes in his introduction, “The entire study hinges upon the controversial notion that it should be possible to measure an underlying political potential, not just a stated political commitment. But this potential can only be grasped dialectically, as both a reflection of objective political conditions yet also in some sense anterior to politics” (xxxviii)—so that the “prepolitical” core of politics may emerge. It was my concern to try to identify this “prepolitical” core of public unreason—the unstable nuclear material at the heart of it. This I would find both in fascism and populism, but also in the central use of unreason in modernism and the avant-garde, on the one hand, and in the quasipopulist form of movements opposed to fascism: anticapitalism, Occupy, Black Lives Matter, and #MeToo, on the other. A big ticket and an (overly) ambitious one, I grant. This is how I laid out the project in my syllabus:

This seminar will bring together several interrelated areas of inquiry: 1) critical and psychoanalytic theories that address the genesis and form of “unreason” in modern culture and public art, including Critical Theory after Dialectic of Enlightenment and The Authoritarian Personality and psychoanalytic theory from Freud to Žižek; 2) theories of language and the public sphere from Habermas to ideology criticism; 3) theories of populism, racism, xenophobia, fascism, and gender and class antagonism; 4) popular movements that are relevant to these theoretical approaches, from hyper-nationalism to fascism, populism, and authoritarianism; and 5) works of modernism and the avant-garde that reflect on, diagnose, or exemplify questions of public unreason, from surrealism to the present. [. . .]

Learning outcomes (course): 1) understand and use basic concepts such as modernity, the public sphere, reason and unreason, identity and identification; in relation to works of art from 1870 to the present, including film, and political movements including democracy, fascism, and populism; 2) think through public discourses on race, class, and gender, particularly recent political issues and movements addressing them, using the theoretical and interpretive tools we have developed; 3) engage in articulate, respectful, and committed discussion with peers on these topics.

The final concern was key: I wanted the inquiry into these questions to take place in my seminar as a kind of model “public sphere”—granting the critique of the Habermasian concept as a counterfactual placeholder for what actually goes on in public discourse. To illustrate what “actually goes on in public discourse,” I began the seminar with an overview of Habermas (with appropriate critical responses) but then jumped immediately to a screening of the 2015 film adaptation of J.G. Ballard’s High-Rise (dir. Ben Wheatley)—an example of the “war of all against all” of total public unreason that is a crucial link between liberal theory and the rise of fascism. At this early moment in the class, everyone seemed to be getting the point and liking it; the question was how long could the illusion of the seminar as public sphere last, given that its core concern was the political use of the irrational? Here is thumbnail of the seminar agenda, seen as a timeline leading to explosion:

Week 1: Social rationality and asociality

Introduction; Jürgen Habermas, from The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere; Slavoj Žižek, from Violence (pdfs); Nancy Fraser, “”Rethinking the Public Sphere”; Michael Warner, “Mass Public and Mass Subject” (pdfs); High-Rise (film, in class)Week 2: Critical Theory in America I

Alexis de Tocqueville, from Democracy in America (pdf); Theodor W. Adorno, from Minima Moralia (pdf); Jacques Rancière, “The Politics of Literature” (pdf); Henri Lefebvre, from Critique of Everyday Life (pdf); guest instructorWeek 3: Critical Theory in America II

Adorno and Max Horkheimer, from Dialectic of Enlightenment; Adorno et al., from The Authoritarian Personality (pdf); fascism in America: Father Coghlin and Ezra Pound, radio speeches; Donald Warren, from Radio Priest; Neil Baldwin, from Henry Ford and the Jews (pdfs)Week 4: The Rise of Fascism

Alfred Döblin, Berlin Alexanderplatz; Berlin Alexanderplatz (dir. Fassbinder; one episode in class); Klaus Theweleit, from Male Fantasies (pdf); Maria Tatar, “Lustmord: Sexual Murder in Weimar Germany” (pdf); guest instructorWeek 5: Fascism

Claudia Koonz, Nazi Conscience; Triumph of the Will (dir. Reifenstahl); Kevin Passmore, from FascismWeek 6: Avant-garde Anti-fascism

Georges Bataille, Blue of Noon; L’Age d’or (film); André reton, Ode to Fourier (pdf); Bataille and Breton, essays (pdfs); Cecile Whiting, from Anti-Fascism in American Art (pdf)Week 7: Psychoanalysis

Sigmund Freud, Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego and Beyond the Pleasure Principle; Herbert Marcuse, from Eros and Civilization (pdf)Week 8: Populism

Ernesto Laclau, On Populist Reason; Kristobal Kaltwasser and Cas Mudde, from PopulismWeek 9: Ideology and anticapitalism

Slavoj Žižek, from Žižek Reader and Mapping Ideology (pdfs); Invisible Committee, Coming Insurrection; Fredric Jameson, “Imaginary and Symbolic in Lacan” (pdf)Week 10: Occupy and Antifa

Mark Bray, Antifa and from Translating Anarchy (pdf); Stepheb Collis, from Dispatches from the Occupation (pdf); Occupy poetry: David Buuck, from Noise in the Face Of; Juliana Spahr, from The Night the Wolf Came; Sarah Larsen, from All Revolutions Will Be Fabulous; Brian Ang, from Communism (pdfs); from Michael Boughn et al., Resist Much/Obey Little (pdf)Week 11: Gender dystopia

The Handmaid’s Tale (second series); Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid’s TaleWeek 12: Social dysphoria

Johannes Göransson, Haute Surveillance; Gaslight [dir. Cukor, in class]Week 13: Black Lives Matter

Amiri Baraka, from SOS; Jonah Mixon-Webster, Stereo(TYPE); Fruitvale Station (dir. Coogler, in class)Week 14: #MeToo

YouTube and podcast materials developed by class: Tarana Brawney; Megan Falley and Olivia Gatwood; Lean Back and The Heart; Sarah Ahmed, from The Promise of Happiness; Sarah Schulman, from Conflict Is Not Abuse; Rebecca Solnit, from Men Explain Things to Me; Kristen Roupenian, “Cat Person”; Roxanne Gay, from Not That Bad: Discourses from the Rape Culture (pdfs)Study day: optional wrap-up discussion

I don’t like to put my syllabi out there, especially when they can be grabbed by unsympathetic or hostile watchdogs of what is being taught in Left academia—but at this point it is all one. The seminar had a high level of initial buy-in and enthusiasm, ending in lengthy sessions at the nearby Common Pub (whether I was around or not). After laying some ground for “what goes wrong in democracy,” I followed with some pure products of unreason, the avant-garde and modernism, seen as predicting the rise of fascism. So far so good, but then came a crucial theoretical moment with psychoanalysis—the discourse all millennials love to hate (what is depth analysis in the age of cell phones and laptops, anyway?). But if psychoanalysis is not on the table, the move to theories of populism with Laclau and ideology with Žižek and Jameson do not work, and the investment in the “empty signifier” of populism that Laclau theorizes, or of the status of the subject as ideological, do not come clear. From there, I turned to quasi-populist oppositional discourses from anticapitalism to #MeToo, each informed by its own particular constitution of “the people,” and in each case tethered by an “empty signifier” or placeholder for an “us versus them” scenario. My thought was that this juncture would have created a set of theoretical tools, insights on the public uses of unreason, that would lay bare the possibilities but also limits of each of these movements. That was by far a stretch—dissensus emerged.

The break, as is well known in the cohort but not otherwise, came with week 11, in the seminar on The Handmaid’s Tale—season 2 of the TV series or the original text if that was too much. I had taught Handmaid’s Tale season 1 in a previous seminar, but season 2 is considerably darker and more brutal (and for that reason I gave the class the choice of watching as much as they could or reading the book). The second series was perfect for the seminar: the relation between patriarchy, sexual violence, and fascism could not be more clear. Unlike the disappointing continuation of the series in season 3, it truly addresses the core violence of fascism, seen in terms that are equally gendered and ideological. But does it depict the real condition of gender and power under patriarchy, or is it a dystopian fantasy (as genre but also as projection) of an imaginary relation between the two? My framing of the question with Freud and ideology critique clearly sets up the second, but what about a materialist feminist reading of the text: that this is the world that women actually live (though we do not yet see bodies hanging from trees)? The second point of dissensus occurred at this crux: can we have this debate within the “normative” framework of a public sphere? What “normative” assumptions can address the claim that patriarchal violence is lived, not only imagined, by women?

This was the crux on which my seminar came undone. The details are for another time, another framework of discussion, but they should be pursued in whatever manner equitable. The Handmaid’s Tale was the crisis of the seminar, after which the discussions of the evocative film Gaslight—which has everything to do with patriarchal violence as ideology, or the poetics of Johannes Göransson’s use of irrational detritus left over from the public sphere in Haute Surveillance—had little impact. Was I professorially mansplaining in organizing the materials in this way? The seminars on Black Lives Matter and #MeToo that followed became painful sites of a dissensus that could not then, or even now, be articulated. What remains is to try to reengage and restate this project, as the consequences of not understanding the present moment surround us like a fog. It also remains to be seen if the students, or the university itself, can evaluate or even value the attempt I made here—with more to come.

Links: Page 01, “Breaking My Own Story”

Page 02, “What Is Mobbing?”

Page 03, “The Aye of Poetry”

Page 04, “My Literary Controversies”

Page 06, “Defend Louisville!”

Page 07, “Difficult Speech @ Louisville”

Page 08, “Nonsite Speech”

Page 09, “Archive News”

Page 10, “Public Documents”

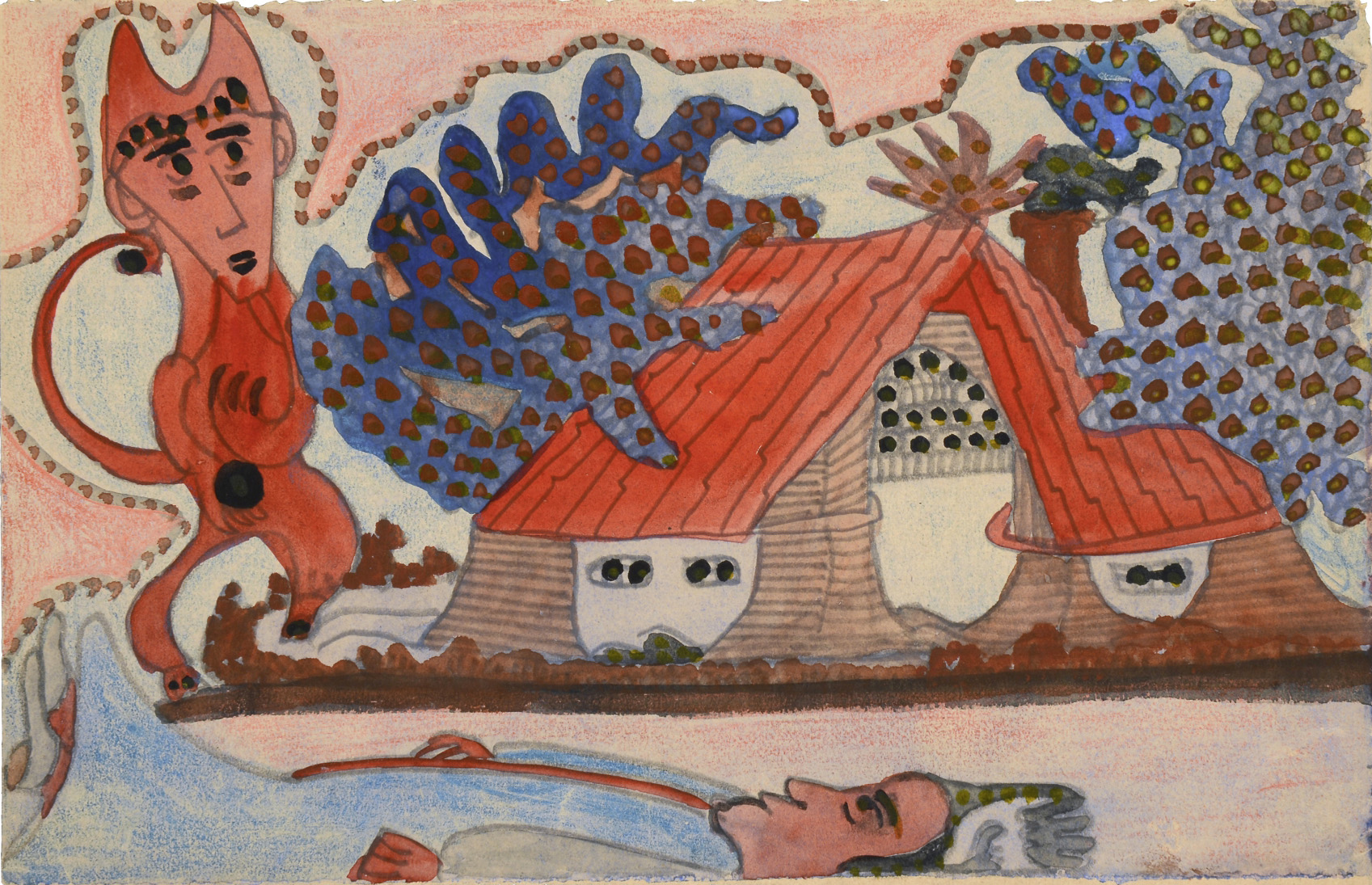

Page 11,” “Endgame Notes”Image: August Klett, untitled, 1927.