Friday, June 16

DB ICE 1040 Bergen auf Rügen > Berlin Hbf

54 Ebertystraße, Friedrichshain, Berlin

Carla Harryman

Ragna Berg

Florian Werner

Ellen Allien

Hamburger Bahnhof

Just about to get there; we have been away. Time crosses space, beginning in Rügen Island and ending in Berlin. Then we were advised to come and we would arrive. The party crowd is aware of its having a location in time and space, had been there for awhile—before we came. The party crowd at the Hamburger Bahnhof, celebrating the new director, a new orientation for art. As we come from a distance, the music invites us in, not yet there. On arrival it is there, an insistent pulse, meditative, cruising on horizontal, an endless plane of immanence, synced in time. He is coming soon, wrote Wittgenstein; he will be coming, he will have come. That must be the new director. Then he will have arrived. Gertrude Stein repeated the phrase, only with modulation. Ellen Allien is the legitimate appointee of the new director, hired to entertain and inspire the crowd, to be a work of art in herself. The party crowd is a work of art in itself, an instance of Gertrude Stein advancing in time. As the director himself had written, “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world“—that is the principle of new art at the Hamburger Bahnhof. It is raining, the crowd is moving slightly then more openly, Ellen Allien gestures to the sky, arms raised, rain is coming down. A steady pulse of the language of limits becomes an episode in time and space. We are not afraid of speaking.

A man coming.

Yes there is a great deal of use in a man coming but will he come at all if he does come will he come here.

How to you like it if he comes and look like that. Not at all later. Well anyway he does come and if he likes it he will come again.

Later when another man comes

He does not come.

Girls coming. There is no use in girls coming.

Well anyway he does come and if he likes it he will coming gain.Ellen Allien is the legitimate heir of Gertrude Stein. Nonsense, she pushes a button and there is a new orientation to the beat. Nonsense. Pulse, difference. Slight movements under an umbrella, the umbrellas are folded. We learn the new meaning to experience time and space, under the auspices of the new director, as an example of the new art. The art is coming all over with newness, like Gertrude Stein coming to Radcliffe, GIs arriving in the Bavarian Alps. The movement begins with a slight dancing, becomes more pronounced, is shared by many in the crowd. Finding a position in the middle, unable to really get a look at Ellen Allien, stepping back, her arms are raised with the beat. And a gigantic pause makes ensuing pulse more danceable, this is the basic grammar of techno. Nonsense. Now take a position a bit farther back, focus and click. On the pause that makes the pulse happen. Let us say what Ellen Allien teaches: electronic dance music teaches. She is the instructor of the moment, hired by the director, as an example of the new art. Her whole life is oriented toward this moment of instruction, in the form of a work of art, a way of being historical. This is the mandate of the Nationalgalerie der Gegenwart: to preserve the present as ethical obligation in the form of Ellen Allien and the crowd, moving under rain, skies now clearing, continuing as may be, a work of art.

“To imagine a language . . . .” Berlin is increasingly bilingual. We are right at home again in alterity. Our friend may know the director. We have been in touch with Florian Werner, exile from the salon of Gertrude Stein. All of them now are expatriates, including the ones who only live here. So much we have in common, renewed on a yearly basis. Berlin for mine! wrote Claude McKay in Home to Harlem. Coming from the east, the first inkling of arrival in Berlin is Spandau, prison exile of Rudolf Hess. Franz Biberkopf, to make the historical point more clearly, having just been released from Tegel, is now out on the streets. “We believe in art with complete openness and transparency”—what we would like to experience in Berlin. History teaching us how to be more transparent. Florian Werner’s negotiation of history and transparency in Berlin can almost not be spoken. It is at the cusp of history to be transparent, as war rolls in from the east. One may take a position in public that could be a matter of controversy. Just so, we meet with Florian Werner at his Lieblingsort in Kastanienallee, though the word has an alternate meaning on a sign for dog food or trash removal. Der Wald ist unser absoluter Lieblingsort would contain both senses. We can talk about anything we like, including troubles of the day in the public sphere. Our private destiny was to arrive in Berlin, at around six in the evening, and meet Florian Werner at Hamburger Bahnhof. “. . . is to imagine a form of life.”

Coming from the north, we exit the train one stop early at Gesundbrunnen, take the S-Bahn clockwise four stops to Landsbergerallee, walk painful cobblestones a few blocks to Ebertystraße and our arrangement with Ragna Berg. Approximately one year prior we had landed at the same address, anticipating a long weekend of art in Berlin, to be surprised at positive test results and a history that has been recorded elsewhere. Now Ragna greets us with smiles, we are on a personal basis, she is happy to be elsewhere for a week, and we re-set the clock to present time, 2023.

Saturday, June 17

Gerhard Richter, 100 Works for Berlin

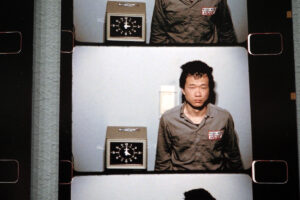

Tehching Hsieh, One Year Performance 1980–1981

(Time Clock Piece)

The Art of Society, 1900–1945

Neue Nationalgalerie

Let me explain the compulsion to repeat. Everything about Gerhard Richter’s work is about a return to a present state. That is his radical presentness, which reproduces itself as a condition of renewal every time. The present, then, is a kind of refresh function, as on a computer screen. In former times, screens would flicker when the refresh rate was not enough; modern technology has perfected an instantaneous retrieval. Instantaneous retrieval is a necessary component, as well, of on-demand music platforms like Spotify, as we learned from the Netflix series The Playlist. It is technically impossible to make retrieval instantaneous, though that is what consumers want, but the redundancy of continuous search results allows for a small snippet of searched material to be played, as it waits for the streaming packets to come. Such a platform for the illusion of instantaneous time is at the core of Gerhard Richter’s 100 Works for Berlin, itself a kind of instant retrieval of his representative works or greatest hits, played to audience perfection. The work is compelling and addictive, the release of pleasurable endorphins prodigious—a result of the enhanced technology of painterly technique Richter employs to create an illusion of a complex surface that instantaneously arrives, exactly at the moment we see it. The 100 works of the exhibition title have been arranged to give the shifting present of viewing their value through a continual refresh rate, one that at times breaks from the “simple present” to a more complex presentness of seventy years of German history. There are a few scattered references to that history on view, flattened and distressed like Onkel Rudi. A rhetorical effect opens at this point, obscuring what is assumed to be a “platform” for any present tense. Thus Richter’s historicism, to claim the past in a form of calculated immediacy.

The opposite principle was on view in the work of Tehching Hsieh, yielding a complementary logic that showed no scruples in presenting art as a matter of present-tense survival, contingency on a global scale, rigorous devotion to discipline in the absence of any recognition. Where opulence and technology define and distort the present surfaces of abstraction in Gerhard Richter, asceticism and poverty are argued as values removed from context in the work of Tehching Hsieh. Then to be sublated by the modern museum, by the world of art as its own horizon. Tehching Hsieh in his displacement as universality is thus misrecognized in the form of curatorial argument that enhances the value of Gerhard Richter, extended to the historical project of modernism in postwar Germany—it is as big a project, and as grand a deception, as that. But the work of Tehching Hsieh remains what it is in its irreducible temporality, as a pure product abstracted by history. The work on view comprises 8760 photographs from a year-long performance where “the artist photographed himself punching in on a time clock every hour for a year. The sleep deprivation thus caused provoked a kind of delirium, causing a number of photographs to fail,” we read in the curatorial copy. Time measured in such a regular way that it becomes a universal ideal as measured against the limits of the human body and mind, which are merely contingent. Let there be no mistake: the universal is what Tehching Hsieh addresses, what it “means to be human” or a “what it means to make art,” as reduced to a question of bare life. Modernism is hardwired as a form of constraining modernity whose recognition converts, instantaneously, to a work of art. It is the most difficult conversion imaginable, and Tehching Hsieh deserves our gratitude and respect—but with equal suspicion of the aims of the museum in celebrating his work as primitive accumulation at the most basic level. His work accomplishes a platform for the present, painfully executed, in which we are allowed to move effortlessly.

The museum speaks history as its own kind of broken language. Thus the effort to define the modern project by the absence of contrary tendencies that interrupt it. This is only one of many ways in which the sum total of all human experience adds up. Such is the ideological dogmatism of Berlin—that in its fragments and disruptions, the more encompassing whole of the universal emerges. So the dome of Reichstag over the remains of the blasted building. Or the parody of the Reichstag in the Humboldt Forum, whose ersatz dome is a mere copy of the universal, opening to a series of courtyards, exhibition spaces, and cafés for the tourist trade. Transparent access in the denial of what came before—a sequence beginning with the Hohenzollern Palast, whose destruction was completed after the war; rebuilt as the Palast der Republik, complete with the People’s Chamber, bowling alleys, and bus parking; and on to the present tomb, with fake eighteenth-century façade on Unter den Linden and anonymous corporate grid by the Spree. The Mies van der Rohe Nationalgalerie is perhaps its equal as historical subterfuge. The exhibitions on view celebrate its years-long renovation, but nothing can be done about the boxlike sterility of its glassed-in upper level, now completely empty, or the exhibition spaces needed to be filled with high-end art to complete its rationale. So the portentously titled “The Art of Society,” displaying abstraction with a social theme (after the influence of Walter Benjamin) that leaves out the unrepresentable gaps that made modernism historical to begin with. Otherwise put, this was art on a scale that cannot be done—the displaced totality of modernity reified in a transparent box.

Siddhartha Lokanandi

Triangle of Sadness, dir. Ruben Ostlünd

Babylon Kreuzberg

The fact of modernity is elsewhere. It takes place in sequences of temporal units, each one defining a space. The museum, without doubt, is an ur-space that instructs, giving the measure to other spaces as encountered in time. Foucault theorized heterotopia as a space of difference, the perverse double of the sterile concept of utopia, which he subjected to ruthless critique. Such a heterotopia might be the glassed-in box of Mies van der Rohe’s museum, housing differential particulars known as modern art. Such might also be the one-off project of a foreign language bookstore known as Hopscotch Reading Room, run by book merchant and scholar Siddhartha Lokanandi. Stopping by briefly, we note he has a workshop in translation going on in the courtyard or Hof, behind which were unsorted stacks of books. In the proximity of hybrid space, articulated by difference and open to the city surrounds, is Park am Gleisdreieck, where three intersecting transit lines meet, a former railway yard since refunctioned as multi-use space. “A major accident at the triangle happened on 26 September 1908 when two trains collided. One car derailed and fell from the viaduct, killing 18 people and injuring 21. . . . Since then there is no direct rail connection between the two lines at Gleisdreieck.” An historical elsewhere has been imported to the center of the city and thus one can live, domestically but decentered as André Breton would have it. The best of both worlds is the beer garden Brlo, a collection of picnic tables under latticed netting that opens to the park and its activities. Thus Park am Gleisdreieck is a definitive modern space, a livable heterotopia. From Gleisdreieck to Kottbusser Tor is a short trip on the U1 or U3, to find that every station on the U-Bahn has its history. We wanted to enter into the fantasy space of director Ruben Ostlünd, in his elsewhere comedy of lifeworld aporia titled Triangle of Sadness. At Babylon Kreuzberg art house cinema, only Barbie is now showing at the present time. “To live in Barbie Land is to be a perfect being in a perfect place”—thus Foucault. In Triangle of Sadness, a stereotypical couple of fashion models finds itself on the cruise ship from hell. They end up stranded on a tropical island and struggle to survive. Knowledge and power are decisive for their chances of survival, to the point that stereotypes unravel into basic human need. A decolonized subject from former times takes control, demanding sexual favors for water and food. The ending is ambiguous.

Sunday, June 18

Eugene Ostashevsky

Oona Ostashevsky

Mara Ostashevsky

Donna Stonecipher

Berlin Book Festival

Bebelplatz

Sleepless, by Peter Eötvös

Staatsoper Unter den Linden

“Why didn’t I call in Karpinsky” is Viktor Shklovsky’s line from his essay “Plotless Literature: On Vasily Rozanov,” from the first issue of Poetics Journal. Whenever I think of the poet and translator Ostashevsky, simply in terms of his name, that line pops into my head. Shklovsky writes: “We are given an individual in bits and pieces that seem to someone we already know, but only much later do the fragments jell, at which point we have a coherent biography of Rozanov’s wife, which can be integrated by extracting all the remarks about her and grouping them under the rubric of ‘the wife.’ The unfortunate diagnosis . . . also appears for the first time as a simple reference to Doctor Karpinsky’s name” (135). Hence the calling of the name Karpinsky, which must refer to someone who can solve a problem, give an answer to an unstated question, but it is unclear what. Repeating fragments like a name, a personality builds up. My visit last year to Ostashevky had ended by diagnostic anxieties of the COVID duration, hence my eagerness to see him again. He had only time for a Sunday morning cup of coffee before leaving for Armenia and a conference on literary translation. We have much to say to each other and catch up quickly, looking ahead. The level of human scale at breakfast. Both daughters venture forward and I take the picture of one in the attitude of a cat, which she performs flawlessly. Then I find my way across an area I barely know, through a park with Cold War references: Bayerischer Platz. Shklovsky again: “Thoughts summarized in artificial sets turn into a single road, into the ruts of the writer’s thought. All the varied associations, all the innumerable paths which run from every thought in all directions are smoothed out” (139). That is not the ending I intended. Our conversation built on fragments but was sufficient in itself. In that sense, Ostashevsky is a prime connection to Viktor Shklovsky; he gets the nonending.

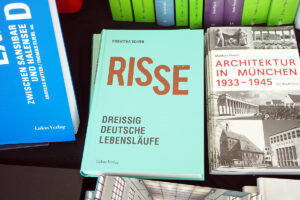

In medias res. The stack of books unpacked, set out in ordered rows, sorted by author, content, genre, publisher. A categorical scheme for ordering knowledge as assembled in one place, Robert Smithson would point out, is a form of reverse entropy. The sandbox separated into black and white grains, rotating clockwise like one of the innumerable galaxies before turning into black holes, reduced in size to a portable paperback. The location of the Berlin Book Festival this year, after its announced theme, takes place on the site of Joseph Goebbels’s book burnings in 1933. Bebelplatz, a node of the geographical unconscious passed by without notice on Unter den Linden. In homage to its former perfidy, an installation of large format photographs of other sites across Germany where book burnings took place. A special edition of Erich Kästner‘s Über das Verbrennen von Büchern is produced for the occasion—in whose preface one reads: “Am 2. Mai 1933 besetzt die SA das Verbandshaus der Deutschen Buchdrucker in Berlin und damit auch die Zentrale der gewerkschaftlichen Büchergilde. In der Folge werden Zahlreiche ‘Gildenbücher’ verboten, darunter Werke von B. Traven, Upton Sinclair, Arnold Zweig und vielen mehr Schriftstellerinnen und Schriftsteller, deren Bücher ebenfalls in diesem schicksalhaften Monat den Flammen zum Opfer fallen.” The original German will suffice, so as not to increase entropy. A permanent monument titled The Empty Library by sculptor Micha Ullman is a glass-covered opening to a space beneath the plaza, where empty shelves that could house all 20,000 burned books may be seen. Are there the same number of books on display in the festival today, one may ask? A meeting the poet and translator Donna Stonecipher, friend from many visits to Berlin, is arranged; I should easily find her as she is tall and has red hair. Circulating among the publisher’s stalls, there are numerous titles to note, too many to take home (another instance of entropy). I am especially interested to photograph design ideas to inspire my publication plans later. What Nietzsche meant by the Will to Power must end in a book: the persistence of the German publishing industry after World War II. Hovering over a catalogue of the architectural drawings of Albert Speer, I calculate their proportion of interest and weight. Centrifugal and centripetal is the destiny of books.

Berlin as a text not work, one may say—but a place where one encounters many works, seemingly produced on a daily basis. The literary life is as impeded as anywhere, but there are ways to be found to an articulate public. Even so, the erosion of the independent bookstore inexorably proceeds, with a notable reduction in stock visible year to year. Then there is public funding of cultural institutions on a scale unimaginable anywhere else; this is not simply a matter of good will but Realpolitik, competing with the East in former times and now to enhance Berlin as capital, where three operas are roaring back after COVID. Tonight we will take in a recent work by the Hungarian composer Peter Eötvös, libretto in English, setting in Norway of unhinged depravity and need, somewhere in the presocialist past. My memory is reduced to the many handouts and programs of cultural events, a knowledge base I add to with each visit. In this case there is an innovative set design in the form of a gigantic fish, to depict Norway, which rotates into a hotel and bar/brothel where vigorous Norwegian fishermen drink and celebrate their fish in a rousing chorus while thoroughly loaded. In this setting a tale of nordic depravity unfolds: he impregnates her, as she is a minor she is thrown out of the house, he murders to cover it up, they are on the run and treated as outcasts, the “black man” appears who susses out the crime, they hang him, she marries another but dies by her own hand. I think this is the order of events, but how can I be sure without the program? The impact is in its portrayal of bare life upgraded to aesthetic enjoyment, in the company of Janacek and Britton, a precarious tale about existence. The farther north one goes, the more existence is compelled by its own destruction, as by a magnet. In the lobby between acts another drama unfolds, of fashionable Russians in exile or on business, possibly cinema people—I recall a woman with full body tattoos and designer black dress—discussing literary aspects of the work with energy and sophistication.

Monday, June 19

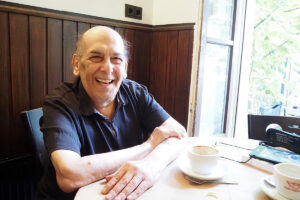

Stan Persky

What did the poet in transit do in Berlin on Monday, July 19? How did he find his way through tiled corridors of underground transportation? At what exit did he emerge? In what district was his morning appointment? Was the meeting with the older poet in a café, bar, or restaurant? What did they discuss—and in what order? Were literature and the literary the most important topics of conversation? Poets and one’s known associations with them? Literary controversies and their outcomes? What about wars in the East? Political views and the hazards of expressing them? The crisis of American poetry, or the decline of the university? The attractions and dilemmas of exile, and for how long has one been out of the country? Length of residence in Berlin and economic viability? The frequency of visiting the cultural and economic changes registered over time? Someone who hated someone and whether that was final or irrevocable? Someone with a reputation for meanness restored to civility in the space of two hours? Slight hints of sexuality and preferences, established relationships and transient ones? One’s military service or avoidance during the Vietnam War? Being tattooed in the merchant marine? The orphic tradition in San Francisco, the Spicer Kreis, the pecking order of poets, attractions and repulsions? How to write the myth of Orpheus in the age of the internet? Is what Jack Spicer meant by translation possible in the age of Large Language Models? The publication of a book titled Language by the aforementioned author, and its provenance by White Rabbit Press? Where did the poet in transit recently acquire a copy and how much did it cost? Is it possible to include a reference to Robert Duncan in this conversation, circa 2023? And who are the authors in eternity? Are we as poets in transit confined to mortal time? Am I speaking for myself, or is identification possible across generations? What is a generation, anyway? Does it have any binding force? Is the aesthetic a kind of genetic materiality that traverses our lifespans? Would I send the older poet my experiment in ludic translation, would he admit it into his confines of relevance? Can poets from succeeding generations inhabit the same time and space, as agreed to for about two hours in Charlottenberg?

On that day and time, I spent several hours over coffee with Stan Persky, one-time ephebe of Jack Spicer’s circle in San Francisco and subsequently Vancouver poet now living in Berlin, accessing whatever came to mind. Persky had made contact over Facebook when I mentioned traveling to Berlin; I had been aware of his online critical writings on poetry and politics, finding in them a disciplined thinking on the Left that I often miss with contemporaries. We made plans to meet when I was in town. Persky has a unique and wide-ranging bibliography, with a number of titles of interest I did not know—beginning with Lives of the French Symbolist Poets from White Rabbit Press; then The House that Jack Built and At the Lenin Shipyard from New Star Books; and on to Flaunting It: A Decade of Gay Journalism, Buddy’s: Meditations on Desire, Autobiography of a Tattoo, and On Kiddie Porn, from the same press. I feel as though I am giving a responsible introduction to a poetry reading in San Francisco circa 1985, but it is later and I need to catch up. If the author is in eternity, it must be in the form of an index to his books. Persky has been coming to Berlin over twenty years and recently established residence—seems like a good move, with a window on events now unfolding on a global scale which he is writing about. We cleared the censorship of Left denial over the war in Ukraine, which both parties agreed is a not further episode in the Cold War between NATO and the Soviets. The author, I have increasingly felt, is a site in Smithson’s sense, of almost geographical specificity. Hence it was important to encounter the author in situ, while the spiral jetty of his works and days spins outward in eternity.

Ulf Stolterfoht

“A no-man’s-land emerges,” in the words of Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe, between “relations of equivalence and relations of difference.” Two poets, by necessity, create a no-man’s-land between them; this is true in every case. To get from one to the other is a disciplined negotiation. Ulf Stolterfoht is the poet writing in German I most admire, whose company I seek whenever I am in Berlin. Often he is elsewhere, in the Austrian Alps or at a literary conference, as he is a master of his own time. When he is in town, he may be found at Jonas in Naumannstraße, a neighborhood bar that I have now visited many times to have become recognized, accepted. A tall blonde beer will be served at a table either outside or inside; there is internet connection and people at various stages in their lives. The life course as a way of measuring time in the social democratic state. “You could say I was on anything / but a roll,” as Bob Dylan would put it. This is what it means to be literary in a no-man’s-land of the quotidian as pure product of where one is. It is a source. To get there I must return on the U-2 to Gleisdreieck, from which I think to walk through the park southward to Yorckstraße, there to meet Carla coming down the S-Bahn if all goes well. Then we would go together to Julius-Leber-Brücke, close by the cafe. Relying on the phone map gets me entangled in a mare’s nest of railway lines at the lower end of the park, signposted as a “wilderness zone.” There is no exit but a threatening space of overgrown hedges used for nefarious purposes, it seems. I go through a chain-link fence into a Schrebergarten, itself a topiary maze of small houses and lots. After several right angle turns with no obvious exit, there is a way out to an anonymous boulevard with roaring traffic that connects to the designated station. Except that there are two of them—one on the U-Bahn, one on the S-Bahn, as any local person would know. After more communication follies Carla arrives; we go one stop to Julius-Leber-Brücke, arriving at Jonas to be treated to a beer, only an hour late.

It is Ulf’s birthday; we are on the way to celebrate. “A birthday is a special occasion,” says the waiter in the Chinese Restaurant in the Woods (a scene from David Cronenberg’s 1999 film eXistenZ). Ordering the “special” triggers the next move in the game architecture, and unknowable sequences unfold. But we are not in that movie; it is a special day for Ulf—the numbers add up and turn over one notch of an automatic numbering machine, I once wrote. We join the party at an Indian restaurant a few blocks away. Ulf’s entire family is there: Annete, Lucy, Pippa, Ulf’s son and wife. To be clear: Ulf has just turned 60 and it is a special occasion, a plateau in life. Only last year he was recipient of the Lyrik-preis der Südpfalz, one of his many awards. Here I am again making a responsible introduction for a reading I would love to bring to Wayne State University, but fat chance of that. A reading interspersed with commentary has been put up online by West Deutsche Rundfunk: you should listen to it now. The variation of consonants and vowels conveys an equableness of tone that extends to a literary Weltanschauung that can only be described as beneficent. In an early essay from Holzwege, Heidegger attacked Jaspers for maintaining that a conceptual framework could be possible in an existential ontology—an attack on any conceptual scheme whatever as “representing” existence. For Heidegger, predicates are merely “regions” of being. Stolterfoht knows these debates and we have discussed them over beers in Jonas. They harken back to his early days in Tübingen, where he imbibed that tradition. In bringing the existential to poetry, Ulf reverses field: predicates have an ontological being. Hence the title Fachsprachen, the technical vocabulary that overturns the lyric tradition of “poetic diction,” the language only appropriate to poetry. In German, the lyric (as existential, perhaps) restricts meanings to that which it presents; Ulf admits the inadmissible in what counts as “poetic.” A no-man’s-land emerges which becomes the recurrent source of existence in everyday life. That is the dinner party we were invited to, and it was no better nor worse than that. It was a special occasion.

Notes and links

Texts (July 16): Gertrude Stein, from “Identity a Play,” [citation t.k].

Translation of German quote (July 18): “On May 2, 1933, the SA occupies the Verbandshaus der Deutschen Buchdrucker (Association of German Book Printers) in Berlin and with it the headquarters of the trade union Büchergilde. As a result, numerous ‘guild books’ are banned, including works by B. Traven, Upton Sinclair, Arnold Zweig and many more writers whose books also fall victim to the flames in that fateful month,” including those of the author. Wikipedia notes: “Kästner witnessed the event in person and later wrote about it.”

Images: all photos (c) Barrett Watten 2023; reproduce by permission only.

For travels in Iceland, Magnetic North I here.

For Norway, Watten/Viken and Utness families, Magnetic North II here.

For Oslo to Rügen Island, Magnetic North III here.

For last days in Berlin, Magnetic North V here.