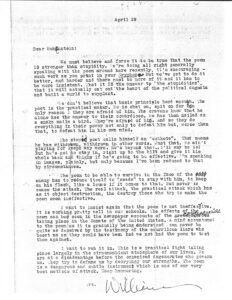

Working through my archive, a copy of the above letter from William Carlos Williams, dated “April 29” and addressed to a “Rubenstein,” turned up. Given the degraded quality of the Xerox, it must have been passed around from hand to hand, and is now far removed from its origins. I have no idea how it came into my possession; my impulse was to distribute it forthwith as widely as possible, given our situation four days before a decisive political event. It does not appear in Williams’s Selected Letters, but an article from the William Carlos Williams Review (here) gives a thumbnail history. The addressee is Richard Rubenstein, editor of a little magazine The Gryphon, a poet associated with the emerging Beat movement in San Francisco who died of the effects of psychiatric treatment in 1958. The date is 29 April 1950, at which time Williams was recently investigated by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) for his association, I now believe is likely, with Popular Front groups in the Spanish Civil War but reputedly for his friendship with Ezra Pound, which resulted in his being denied appointment as the Poetry Consultant to the Library of Congress in 1949. In its resistance to the “stupidity” of “political dogma,” Williams writes: “A mind accustomed to the poem as it is gradually being understood can never be quite as deceived by the testimony of the scurrilous liars who beset us as they could have been had we not had the poem to test them against.” Four days before our opportunity to run the scurrilous liars out of power, his words have a new force.

Dear Rubenstein:

We must believe and force it to be true that the poem IS stronger than stupidity. We’re doing all right generally speaking with the poem around here recently, it’s encouraging—such work as you print in your Gryphon. But we’ve got to do it better, and harder and there must be more of it and it has to be more insistent. That it IS the answer to “the stupidities,” that it will actually eat out the heart of the political dogma and build a world to supplant.

We don’t believe that basic principle hard enough. The poet is the practical maker. He is shat on, spit on for one only reason: they are afraid of him. The cravens know that he alone has the answer to their cowardices. He has them nailed as a snake nails a bird. They’re afraid of him. And so they do everything in their power not only to defeat him but, worse than that, to defeat him in his own mind.

The stupid poet calls himself an “esthete.” That means he has withdrawn, withdrawn in other words. Just that. He ain’t playing for keeps any more. He’s beyond that. I’ll say he is! But he’s got to stay in, right up to the hilt and give it his whole back and thighs if he’s going to be effective. I’m speaking in images, plainly, but only because I’ve been reduced to that by circumstances.

The poem to be able to survive in the face of the enemy has to reduce itself to “seeds” to stay with him, to keep on his flesh, like a louse if it comes to that. But never to cease the attack. The real attack, the practical attack which has as its object destruction, the [sic] destroy those who try to make the poem seem ineffective.

I want to insist again that the poem is not ineffective. It is working pretty well in our schools. The effects of the poem can be seen in the newspaper accounts of the grotesqueries taking place in the Senate of the United States. A mind accustomed to the poem as it is gradually being understood can never be quite as deceived by the testimony of the scurrilous liars who beset us as they could have been had we not had the poem to test them against.

I want to rub it in. This is a practical fight taking place largely in the circumambient atmosphere of our lives. We are at a disadvantage before the organized degenerates who govern us. They try to defame us by decrying our strengths. The poem is a dangerous and subtle instrument which is one of our very best methods of attack. Keep hammering.

Yrs. [signed] Williams

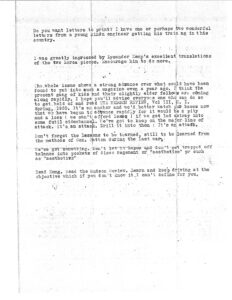

The letter was not printed in The Gryphon in its entirety, but restored in the cited article as well as circulated among poets, whence it came into my hands. The back of letter continues with observations that date Williams’s politics both in terms of his World War II antifascism (admiring Gen. Patton’s take-no-prisoners attitude, recalling the militarism of the introduction to The Wedge) and his friendship with Pound (“Read Kung”). Williams was not politically consistent in terms of explicit doctrine, but his sense of poetic agency—”The real attack, the practical attack which has as its object destruction, [to] destroy those who try to make the poem seem ineffective”—is. Poetic agency puts forward a dedicated antifascism via the means of democracy.

Do you want letters to print? I have one or perhaps two wonderful letters from a young Hindu engineer getting his training in this country.

I was greatly impressed by Lysander Kemp’s excellent translations of the two Lorca pieces. Encourage him to do more.

The whole issue shows a strong advance over what could have been found to put into such a magazine even a year ago. I think the present gang of kids and their slightly elder fellows are coming along rapidly. I hope you’ll advise everyone who can do so to get hold of and read THE HUDSON REVIEW, Vol. III, N. I. Spring, 1950. It’s an anchor and we’d better watch our bases now that we have begun to advance rapidly for it would be a pity and a loss (we can’t afford losses) if we get led astray into some futile side channel. We’ve got to keep on the major line of attack. It’s an attack. Drill it into them: It’s an attack.

Don’t forget the lessons to be learned, still to be learned from the methods of Gen. Patton during the last war.

We’ve got something. Don’t let it lapse and don’t get trapped off balance into pockets of discouragement or “aesthetics” or such as “aesthetics.”

Read Kung. Read the Hudson Review. Learn and keep driving at the objective which if you don’t know I can’t define it for you.

Notes and links

Uhland, Sam. “Richard Rubenstein’s Correspondence with William Carlos Williams.” The William Carlos Williams Review 20, no. 1 (Spring 1994): 65–68.

[links t/k]