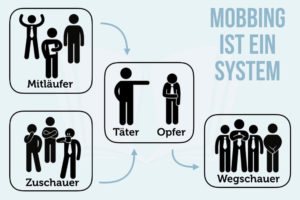

Mobbing and bullying are two terms describing linked phenomena, common both in the academic workplace and in online culture. Guess what? I have been subject to both of them, the former in an unusually pure form with last spring’s online blog campaign and petition site. Both were intended to leverage classroom and conduct issues at Wayne State University, and the process is still unfolding—WSU AAUP-AFT’s strong and unambiguous support of my rights to my academic freedom and employment as a professor are evident in the language of our grievance against the university’s ill-considered action. Part of the miscarriage of justice here takes the form of substantial due process issues—lack of ability to respond fully to what has been said about me; absence of evidentiary standards or cross-examination; and a “preponderance of evidence” standard that falls short of “clear and convincing” proof of anything. The students who banded together to call me out are the FERPA warriors of Wayne State University—they think they have a right to say or do anything they like about a professor, while they are protected by privacy precisely by their status as students. This is why, by the way, this is not a free speech issue—the students assume a right to speech where I have none, in the absence of which they have constructed quite a verbal safe space.

I am uploading a short, trenchant article on academic mobbing—which is especially virulent due to the pseudo-“protected” nature of academic institutions—and a comprehensive article on bullying and mobbing by WSU scholar Loraleigh Keashly. In the first article, the charge of “bullying” becomes the incitement to “mobbing”—precisely what is being attempted with me. It is crucial to see the link between the two—the projection of “bullying” onto the target (me) becomes the collective call for the mob to attack, circle, and exclude. In mob behavior, as well, people say and do things they would never have the temerity to do individually, and this is even further exaggerated in online communities: virtuality and de-individuation, which is necessary to form the mob, go hand in hand. The second article demonstrates the prevalence of bullying, and to a lesser extent, mobbing in academia, but a key insight is that bullying comes in many forms and from many directions—it is a reinforcing behavior. There is bullying from above, from below, from colleagues and peers as much as superiors and subordinates. Bullying is also institutional—the President or state legislatures bully academics in ways that contribute to the larger phenomenon. Crucial to the present situation, then, is bullying from below by students in the neoliberal, corporate university where they are privileged as clients and protected by entitlements. The following passages from the article have a familiar ring: elements of the ongoing situation with me and the cabal of my former students should not be missed:

Section 1 (pp. 3-7) discusses the special characteristics of academia and academics—such as autonomy, tenure, the role of contestation and challenge in argument, disciplinary differences—leading to tensions that may result in bullying or be misrecognized as it.

Section 3.2 (pp. 33-35) on the role of interpretation and normative judgments (and, it may be suggested, differences in normative judgments) in assessing what counts as bullying. Mobbing creates collectively “confirmation bias”—everyone is eager to pile on and join in, because they are induced to see the same thing.

Section 7 (pp. 45-51) talks about different actors as well as targets in bullying, particularly p. 45 and pp. 46-48 on students as actors, or “bullying from below,” and pp. 49-51 on the public and the state as “bullying” actors (relevant to online mobbing).

On students as actors: “Students as consumers or clients within a neo-liberal model of higher education may wield considerable power and be permitted greater behavioral latitude . . . that is, contrapower (academic) harassment . . . . As evidenced by the robust literature on student incivility in the classroom . . . students are frequent actors. . . . [Various authors] described behaviors of purposeful interruption, challenging authority, excessive/aggressive questioning of decisions . . . . The case of the student actor is interesting because their activities may be considered counter-positional . . . or ‘bottom-up’ bullying. This challenges the notion of power and what contributes to the power differential. While faculty have significant impact on student experience and fate, students do wield power in the current higher educational context. With the shift to neo-liberal and managerial culture that emphasizes enrollment-driven funding and prioritizing of career-focused training, the student has become a customer and is empowered in that capacity. . . . The increased sensitivity regarding dealing with controversial topics and resultant student (dis)comfort have faculty positioned in the role of classroom manager and arbiter. Thus the environment is ripe with features that would be conducive to bullying and incivility on the part of students” (48).

On high-performing faculty: “Being a high performer can also be a risk factor for being targeted . . . . Specifically, being a high performer in terms of academic achievements when perceived as a threat to colleagues’ statuses, particularly in a competitive academic environment, may make some faculty ‘noticeable’ and, hence, vulnerable. . . . Even senior faculty who are high performers have been found to be at risk” (46-47).

The conclusion: “The examination of actors reveals that faculty ‘get it from all sides.’ They are bullied by internal actors such as colleagues, students and administrators but also by external actors such as the state and increasingly the public through online harassment. . . . The examination of bullying in academe reveals the inherently contextual nature of the behaviors. That is, behavior does not speak for itself; rather, it is interpreted, enacted and experienced in a particular normative and discursive context” (63).

While written in academic prose, there are numerous insights here that can be applied to the present situation and its very recognizable dynamic—so perhaps, in the end, something may be gained from all this.

Documents: Eve Seguin, “Academic mobbing, or How to Become Campus Tormentors”

Loraleigh Keashly, “Workplace Bullying, Mobbing and Harassment in Academe: Faculty Experience”Links: Page 01, “Breaking My Own Story”

Page 03, “The Aye of Poetry”

Page 04, “My Literary Controversies”

Page 05, “Questions of Unreason”

Page 06, “Defend Louisville!”

Page 07, “Difficult Speech @ Louisville”

Page 08, “Nonsite Speech”

Page 09, “Archive News”

Page 10, “Public Documents”

Page 11,” “Endgame Notes”

Page 12, “This Tragedy Is Farce”