[. . .] Have I

studiedall such isolation

just to

be alone?Robinson Crusoe

is a

favorite book. I thoughtit was a true one.

Now I find

I wonder. [. . .]—Robert Creeley

This is a difficult piece to write—to describe my isolation. Making a public case of one’s isolation seems shameful, under any circumstances. It is against the normal condition of sociality, a condition we assume as an aspect of happiness and well being. Poets have found themselves forced outside of normal conditions of sociality throughout history, to the extent it may seem a part of their vocation, even their choice. I have been socially isolated from my work, my students, and collegial life; whether it is the result of an ideological difference proper to my vocation as poet and critic is an open question. Poets often see themselves as an isolato, “a person who is physically or spiritually isolated from others.” We have been collectively isolated, as well, by conditions of a disease we must sequester ourselves from. These are the circumstances in which I am working, then, in isolation.

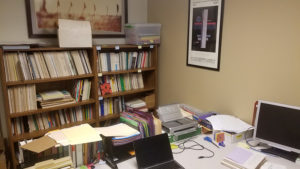

On 7 March 2020, I contracted with Anytime Moving of Warren, Michigan, to move the contents of my office and archive of poetics to my studio space at the Canfield Lofts. My office will remain empty during the process of my grievance against the university for the actions it has taken to deny my teaching, mentoring, and physical presence in my department—harsh and unnecessary measures that were publicized on social media in a way I can only term shameless [here]—and meant to shame. During the period in which the grievance is pending, I further received an order, prior to any resolution, to move the contents of my office and archive out of my department. My archive itself is a complex, on-going work-in-progress, which I have been intensely organizing over the past several years; the disruption this causes is an injury in its own right.

Such a relocation would not be to any space occupied by colleagues—or indeed any person—but to a windowless monad of an office space in a dusty, disused area of an administrative building which likely served as some kind of disbursement office. The dean even sent a PowerPoint of the available space, including an architectural plan, to show how rationally considered this was. My archive would be removed to a tomb, a vacuum, the Gulag, outer space—any number of metaphors to indicate the profound denial and disrespect for my work that was intended. What this is about is not justice or remedy for any unresolved situation, but an exercise in power and humiliation. I was to become a pariah, in short, in a public spectacle of disrespect; in another epoch, I would have been put in the stocks. Rather than accept this condition, I organized my own Plan B, but not without responding in writing, as best I could, citing as well AAUP-AFT’s grievance on my behalf [here], which reads:

> The proposed relocation of his office is disciplinary and retaliatory because he has challenged unfair, unreasonable and arbitrary action that has unilaterally changed his terms and conditions of employment.

> The proposed office is removed from the English Department and other faculty, and amounts to an exile or segregation which damages the reputation and professional standing of Professor Watten.

> There is no reasonable or just cause to humiliate and punish Dr. Watten by imposing juvenile conditions and restrictions on his employment.

The grievance’s wording is apropos; other terms to describe your measures might be sadistic and Kafkaesque. The two offices you mentioned are dusty, windowless monads in an abandoned administrative space, far from not only humanities colleagues but from humans. Thinking that such a fate would be acceptable to an internationally known scholar and poet, member of the Academy of Scholars, and recipient of major awards, is bizarre and offensive. Some of history’s most torturous exiles come to mind when imagining such a scenario. The reassignment of my office and archive to such a location is not a possible solution; if the move is required, I would negotiate another scenario. (Letter to WSU, 13 February 2020)

The letter, of course, had no effect, though the grievance is in process; while the union protested this order, there was nothing to be done about it. It was made, as well, the same day that a third incident of vandalism against my office took place; I was being harassed out of the department. A second letter from the university, on 27 February, doubled down on the order, offering me two offices in the same disused space, stating that “[movers] will be dropping off labels to your office to your office at the English Department this week for you to label your furniture, books, papers and other items by office number and in away that will allow the movers to put them in the proper order in your new offices.” How helpful and efficient! In fact, when I went to my office to organize my own move, I found that staff had already labeled my boxes and files with little tags that read “Barrett Watten,” while oversized “Stay” labels were used for the university’s property—just to keep me honest, I guess. In any event, I found my death by labeling to be premature and asked for the labels to be removed, though the department’s had to stay.

I write these ridiculous details to underscore the Kafkaesque absurdity of the entire process. At heart, too, was a measure of vindictiveness and retribution, as in one passage that reads, “In the alternative, I can arrange to move your literary archive directly to the institution to which you have offered it. I think your prior willingness to part with it and move it to this premier humanities library belies your argument that moving it to your new office will somehow damage your collection or cause injury to your research. The College is not mandating what you can collect, archive, or study, so there can be no infringement of your right to academic freedom.” A combined lack of comprehension and deficit of reasoning is evident here, to which I responded: “The archive is an integral part of my continuing research and creative writing, which draws from the archive and contributes to it. When acquired by a university library, it will be sent to them in a series of deposits over several years, and I will continue to add materials to it.” I should add as well that this entire sequence of letters will be in it—you are now a part of my archive!

When this specter of humiliation arose—and in the fight against being banned from the Louisville Conference [here]—I considered using the slogan “Defend Poetics Archive!” to launch a public support campaign. But the move has been made—a comedic afternoon in which I got to know the two movers P— (body-builder, tats) and M— (elevator phobia, keeps to himself). The archive boxes were wrapped up in plastic and hauled out to the corridor, lined up for the elevator. Getting everything into the Canfield Lofts due to the narrow alley and 26′ truck was another matter; and the timing was not entirely mechanized, due to aromatic breaks. Everything was piled up in respective piles (archives sorted and unsorted; teaching files and books), and has been in a process of reorganization ever since. As a source of value, the archive is indeed productive—it is the focus of my isolation and will be my primary occupation until the grievance is resolved and I am restored. On the very day I retrieved the last of the files, it turned out, the university was shut down; the department is now on lockdown and it would be even more impossible to continue working there. Providentially, then, my archive is in one place, and I am free to work on it. In the coming days, I plan to experiment with uploading selected documents and images online, with commentary; stay tuned.

Notes and links

Photos: Barrett Watten, 3 photos of Poetics Archive, Wayne State University, February 2020; Carla Harryman, Poetics Archive, Canfield Lofts, Detroit, March 2020.

Citation: Robert Creeley, “An Illness,” in Collected Poems, 1945–1975, 488.

Links: Page 01, “Breaking My Own Story”

Page 02, “What Is Mobbing?”

Page 03, “The Aye of Poetry”

Page 04, “My Literary Controversies”

Page 05, “Questions of Unreason”

Page 06, “Defend Louisville!”

Page 07, “Difficult Speech @ Louisville”

Page 08, “Nonsite Speech”

Page 10, “Public Documents”

Page 11, “Endgame Notes”

Page 12, “This Tragedy Is Farce”