The first issue of This (1971) included a short photo essay and memorial to Charles Olson by photographer Elsa Dorfman, who died in May 2020. Bob Grenier, co-editor and mentor, had moved to a small house by the cove in Lanesville, Mass., on Cape Ann, and would have been in contact with Robert Creeley, Larry Eigner, and, through poetry connections, Elsa Dorfman. Olson had recently died (10 January 1970) and I was in the thick of his influence, visiting Gloucester that summer and organizing a reading group on the “modern epic” at Iowa in the academic year 1971–72 that included renowned scholar Sherman Paul, who credited the group discussion in his book Olson’s Push (1978). A signal moment in that seminar was unfolding the Coast and Geodetic Survey map of Gloucester harbor, which I bought when I visited, to provide a “spatial reading” of the otherwise cryptic poem: “In the harbor // Can 9 Nun 8 / Nun 10 Can 11 //// Charles Olson / Friday, November 23rd // #1” (Maximus IV V VI, n.p.; Maximus Poems, 302). From the map, one can track a sequence of buoys in the harbor (termed “cans” and “nuns” from their shapes, presumably) that transposes the subject-centered experience of sighting the buoys to a sequence of signs in space. It is tempting to imagine that Language writing was born right there, though there were many converging influences, never reducible to a moment of origin. In fact, it was the gap between what Olson was seeing and what his poem and the map record that signified, a way of reading that makes clear why the poem had to be written as it was. Many of the short poems from the second volume of Maximus, along with Creeley’s Pieces, were objects of fascination then.

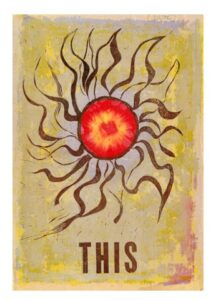

This is the moment of the “radical particular,” about which I write at some length here. And the name of the radical particular is “this,” the title of our magazine but also the focus on a deictic register of time and place seen as central to the entire tradition of writing we were influenced by, from Stein and Zukofsky on through to Projective Verse. Olson’s broadside poem “This,” produced at Black Mountain college in 1952 (see here), used the pronoun somewhat differently—as a Whiteheadian occasion of immanence or the unfolding of solar energy after D.H. Lawrence, perhaps—but no matter. Olson’s large-scale enterprise worked to disclose the conditions of possibility of “this”—within the holistic, embodied, ever-expanding universe that was his larger project. That level of scale, for those not identical to Olson as embodied subject, became, simply, a condition for making meaning. Parole and langue, the relation of signification to language itself, but joined at the hip to an experience of time and place. If one reverses the polarities of that relation, one can “read out” time and space from the particulars of language, making a new continuum. That was the idea—to make new time and space from the radical particular, which Olson for one made available for poetry. As did any number of others, so the question remains: what of Olson’s this was so conducive to its being radicalized?

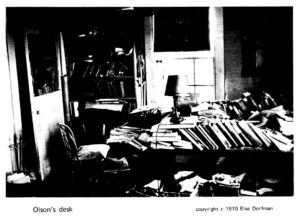

The memorial tribute to Olson in This 1 was, at any rate, only the hint of a beginning. It is to a degree sentimental and certainly founded in affiliation and affection—which are perfectly all right. Dorfman visited Olson and depicts his intimate spaces—his desk, the kitchen in his walk-up apartment in Fort Point, the bar where he poses with another Maximus of Gloucester, along with the friendly barkeep to provide “measure” of the human, perhaps, leaving nothing out. All of this is meaning-bearing, meaning-generating, though later—and now is later. I am reproducing the Olson photos after seeing a Facebook thread from Canadian poet Robert Hogg, with pictures of Olson’s library at the time, as a prompt. From there, I thought to compare Olson’s untidy urgency with Francis Bacon’s studio (a fetishistic site if there ever was one) and my current archive. Meaning is erupting from these comparisons. There are also the two images of Olson from This 1, offering more such turbulent valences.

Notes

Reproduced from This 1 (1971), copyright (c) Barrett Watten and Robert Grenier, 1971; Barrett Watten, 2020; photos copyright (c) Elsa Dorfman 1965, 1971, 2020.