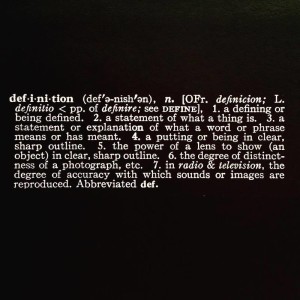

Unlike period style, which has a specific meaning in art history going back to Winckelmann, the term critical art practice has a contemporary but less defined usage, among left art educators for one (see its current Wikipedia stub). It appears in Questions of Poetics primarily in the introduction, and with a larger range of inference. Even so, the distinction between period style and critical art practice is crucial: the former is a set of static attributes, associated with fixed aesthetic or literary periodization, and the latter the real-time engagement with fundamental assumptions of language, style, form, genre, medium, person, identity, discourse, reception, history, and so on:

It is not my intention to recover Language writing’s historical origins but rather to show how the relationships it developed between form and context are the basis of a critical art practice. A critical art practice is one that examines the fundamental assumptions of its genre or medium as the basis for the production of new work. (7–8)

I argue [. . .] that the avant-garde begins with material signification [. . .] but that the radicality of the particular breaks the frame of both work and genre to arrive at a critical art practice that extends agency from the work’s materiality to the question of its genre assumptions, finally intervening in the cultural logic or lifeworld it stems from. Questioning poetry, visual art, or sculpture leads to critical art practices such as Language writing, conceptual art, and installation or site-specific art, to name a key series of examples. These new genres interpret the critical force of their material signification per se, yet the fundamental destabilization that results—the breaking of the frame of work or genre—continues the logic of negativity as an open series of critical interpretations. (8–9)

Marcel Duchamp’s Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even does not lose critical force because it is installed in the Philadelphia Museum of Art; not only does it continue to change the criteria for what counts as art, it also leads to further developments of critical art practice. The material fact of The Bride, as well, continues to signify through multiple frameworks and media. (9)

The materiality of language, in the work of the Language school and elsewhere, was indeed part of a larger cultural logic, but one that was not restricted to affectlessness, simulacrum, nostalgia, and pastiche as the privileged signs of Jameson’s postmodernism. Rather, Language writing and related critical art practices attacked the twin dominants of normative aesthetic form and administrated communication in the period. (9)

Two kinds of materiality particularly intersect in critical art practice: the nano form of signification, in the device of the radical particular; and the macronarrative of material production, in which formal agency intervenes. A third kind of materiality exists in what otherwise would be a seamless critical transition from particular to totality: the material state of a given genre, as historically produced—a form of the collective, congealed labor of the work of culture—in which critical alterity is deployed. (10)

Materiality is motivated, in critical art practice, by the question of what kind of thing something is, involving questions of language, genre, historical context, and cultural logic— not simply that it exists as material. Rather than ending in a kind of mute immanence, as some contemporary materialisms do, materialist art practices are critical interventions.

What does it mean to see Language writing as a critical art practice, in the period in which it emerged, and what does that mean at present? The attempt to confine the avant-garde to a historical series, I have claimed, is a polemic informed by art historical narratives in which the overturning of one school by another is assumed. (10)

At stake in the first discussion [chapter 5] is the variable role of the negative, as materially constructive and historically specific, in critical art practice. In framing the question of negativity in terms of specific contexts and across genres, I am arguing with Theodor W. Adorno’s position that poetic form criticizes society through its formal autonomy, not through its direct referentiality. (18)

What motivates the turn to poetics as critical art practice, apart from the differential negativity that is one of its constitutive features? This might be the same question, in terms of a materialist poetics, as what is a poet/critic? (20)

In this chapter [3], I take up three critical art practices involving language—Language writing, conceptual art, and the most recent, conceptual writing—in terms of how each addresses the question of representing the present, either within a historical frame or without one. Each of these movements constructs its version of “the present” or sees itself as an art of present time in formally and historically specific ways, and in each presentism and periodization are differently engaged in the work’s construction. (137)

Critical art practice is thus a basic assumption that bridges material signification, and especially the key device of Language writing, the radical particular, with larger aesthetic and cultural concerns (including how an active “present” is foregrounded, against the background the past as dead labor, by different art movements). Finally, the “poet/critic” is essentially engaged in a critical art practice, as they interrogate basic assumptions of practice and continue them in a form of critical thinking. In subsequent posts, I will expand on this relation of radical particularity to the version of poet/critic that results.