Friday, June 9

SAS 347 TRD > OSL

Heimdalsgata 35, Gamle, Oslo

Carla Harryman

According to my source, there are three kinds of space: absolute, relative, and relational. Looking for the proper airport code for Trondheim, I became enmeshed in the military and aviation history of its location in Værnes (not, evidently, the Værnes where the village church is located; the place name is repeated at two locations on the coast). Reading the entry, I stop at the exact description of the runway, its length, manner of construction, and what kind of air traffic it serves. “The main runway is 2,999 metres (9,839 ft) long, and runs east–west at 09/27. It is 45 metres (148 ft) wide, plus shoulders of 7.5 metres (25 ft) on each side. The runway is equipped with instrument landing system category 1. . . . ” In absolute terms, the runway thus materially exists. Should an airplane positioned at one end of the runway develop sufficient thrust, given the mass of the airplane and the lift of its wings, it will take off. Pilots know this and rest assured at the controls while passengers suffer through the mysterious event time and again. “Værnes has a theoretical capacity of 40 air movements per hour, but this is reduced during bad weather, so the airport has a registered capacity of 25.” In a given year, three to four hundred military aircraft are served by the facility, the entry goes on to state. What follows is a history of the transition from its use in the German Occupation to an important outpost for NATO, with continuing American military presence, likely being increased as I write.

In relative terms, we are accelerating and gaining altitude, then leveling off, looking down on the airfield and its improvements, noting the many hangers, service buildings, hotels, parking lots, not entirely aware of its military uses in the Cold War. In relational terms, we are on a short-hop flight from Trondheim to Oslo, from the former seat of the Norwegian kings to the global commercial hub of Oslo. Power and influence are centralized in the south even as political control has changed numerous times—and is still relatively in play. Streaming the Netflix series Occupet (Occuped), we learn that a megalomaniac ecofuturist president, in a failed attempt to develop a fusion-based source of endlessly renewable energy from Norway’s untapped mineral riches, cannot prevent a Russian invasion and takeover, whose objective is to control what is left of its oil reserves. Therein a complex allegory of economic frames: the oil that has propelled the Norwegian economy for decades, attracting the troglodyte Russians and their reliance on fossil fuels, versus the cryptic new economy of sustainable energy, an increasingly utopian goal. There is no way for Norway to imagine itself outside the contradictions of the global economy; this is the tragic flaw in the idealism of its nation state. For such a small population, such a large land mass, with such abundance of natural resources, but with such an indefensible coastline (albeit geographical obstacles to invasion), Norway’s future is depicted at risk by means of wildest imaginings. Norwegians themselves speak frequently and openly of such fears.

Meanwhile we have landed in Oslo, where a state of the art rapid transit system delivers effortlessly. The Oslo Metro, we read, “consists of five lines that all run through the city centre, with a total length of 85 kilometres (53 mi), serving 101 stations of which 17 are underground or indoors. . . . In 2016, the system had an annual ridership of 118 million.” Urban rail transport in Oslo dates from 1854, with the first suburban tram line being developed in 1898, and an underground sytem begun in 1912, to be completed in 1928. Something missing here, is being left out. We are an assignment to our destiny in Oslo, of international importance, the linchpin of our journey, prepared for months. At the Central Train Station at any time over the past fifty years, one could pick up Cold War spy novels in Norwegian or English; the paranoia persists as current geopolitical alignments shift. And there is the war, not far in the distance but subtly changing everything; raising a new level of attentiveness that only increases as one moves from west to east. Distinctions of region only proliferate the more global unity is called for, now to be imagined in absolute terms. Hence Sweden and Finland have been added to NATO, transforming Scandinavia as relational space. In the international zone of the harbor, the band strikes up, accordions play, waiters arrive on roller skates, the meal is served. Glasses are raised to our combined and uneven destiny, at a moment in time and space never to return.

Saturday, June 10

Meanwhile Oslo has developed, with a living standard among the highest in the world, and a cost of living to match. In any city new to me, my first desire is to interrogate it, to try to disclose something of its core identity, or to put together a Frankenstein approximation out of a few of its parts. Such must be the goal of the long-running series in the New York Times: “36 Hours in X” (which could be your own back yard but might be Prague, Ho Chi Minh City, or Palermo). Before the 36 hours had elapsed, one had no knowledge of such a place but its location on a map and what one had read or heard about it; after 36 hours, an indelible trace exists, no matter how it was composed. The experiences that will create this indelible trace are largely arbitrary: any combination will do, to create a certainty that “now I know something of X.” In the movie Frances Ha, Greta Gerwig’s breakthrough portrait of millennial angst, the heroine runs up a quick flight to Paris on her credit card only to miss half the weekend due to jet lag. She wakes up at 4 P.M. with sounds of children playing in a creche and a heavy head, standing for all such mistimings of travel. She will not make a connection or achieve her destiny, which rises to an act of knowledge. Just so, Oslo: its indelible trace is a disconnected set of experiences and superficial impressions, approximate distances on the map. These impressions fade quickly into background senses of crowds, buildings, trams, light breeze from the harbor. Of this day, I remember the Botanical Gardens, off the city center, which allowed for a different perspective before we returned to the racially mixed, centrally located district of our fourth-floor Airbnb. Rather than repeat the tourist experience at the harbor, we dined at a neighborhood beer garden that was really not good, though recommended.

Instead of experience, we opt for art. A major new building has opened in Oslo to display with pride its National Museum, just off the harbor and its tourist zone. (Across an inlet, the competing attraction advertises “MUNCH” in ten-foot high lettering, just so no one could miss it. I thought this a novel idea, bringing together dining with art.) The holdings of the Norway’s museum are curated at the level of the game in world museums everywhere: such is the boredom of the national museum, its narrative of becoming Norway seen through the genres and periods of art history. No matter how hard it may try, the collection of European masters is always on the way to identifying the distinctly

Norwegian contribution, once it has achieved its defining moment in romantic landscapes; the defensive perimeterof modernism is always augmented by the Norwegian one-offs—most certainly Edvard Munch!—that are otherwise placed on the periphery; the proliferation of neo-avant-gardes from the postwar period always adds Norwegian historicism to the range of formal strategies proliferating globally. Generally, it is hopeless, begging the question how to think about it otherwise. A glimmer of transformation appeared in the museum’s installation of Ilya Kabakov’s The Garbage Man (The Man Who Never Threw Anything Away) from his

epochal Ten Characters series (1988), a definitive work of post-Soviet art that I was lucky to see at ICA London in 1989 (another arbitrary moment of travel). In addition to its pastiche of the Soviet kommunalka, Kabakov’s installation has the effect of communizing its surrounds; thus the national narrative is displaced. (This effect, a substantial displacement of the weight of convention, turned out to be elsewhere available in Oslo, as we would find the next day.) The substantial holdings of arte povera also created a tension, at least, with monumental narrative aims. The entire floor dedicated to Louise Bourgeois: Imaginary Conversations likewise picked up the counter narrative from

Kabakov and arte povera, making a rhizome of connections between Bourgeois’s work and its influences and followers. While the experience of reading the national narrative is frustrated, demanding everything be relegated to its place, that of Bourgeois led to a differential assemblage that could be followed at will—for which, due to the effort of the major works on view, we had less than fifteen minutes to see, inviting return next day to peruse, at least, the catalogue.

Sunday, June 11

Triangulating incommensurates is not in the guidebook. Travel must be fully planned, booked in advance, set on a schedule that cannot be changed. Travel is also a form of automatism where one decision may or may not lead to the next. Within those two poles “it speaks” and one attends to it. In Trondheim, the Norwegian Resistance dawned as a topic of interest, to pursue later. At the Military Museum, once past the heraldic history, Occupation and Resistance were staged as a series of placards and tableaus, drawing a sharp line between them. A Norwegian “coming to terms with the past,” assessing the degree of consent to the Quisling regime and collaboration with the occupiers, has yet to be achieved. It is coming soon, out of the archives, then. At the museum I picked up the narrative of union leader and Resistance heroine Solveig Lystad, Usynlig i krig og fred (Invisible in War and Peace). Her biography begins: “This is the story of Solveig Lystad, a woman of resistance. The introverted woman—perfect as an operative during the war—silent under torture—invisible in captivity—hidden or forgotten afterwards. Her work in the trade union movement, illegal resistance work, and life as a prisoner of war helped create her complex personality.” The silencing thus starts to speak. In Oslo, I wanted to follow this opening at Resistance Museum at Akershus Fortress, a historical site overlooking the harbor.

National narrative soon takes over, restricting the opening to authorized vignettes, from which, one would think, the country had little to do with Quisling. Still, an unfolding framework is disclosed—for instance, in the failed attempts to achieve a Norwegian Gleichschaltung, the “coordination” to fascist institutions and world view that took place in 1933 in Germany. What stopped it was a teacher’s strike in 1942, which resulted in the arrest of 1100 teachers and deportation of over 600 to labor camps in the north. While their Resistance was not universal, the act prevented the broader nazification of Norway—a lesson about resistance to be taken home.

Thus instructed, we kept some doubts about our agenda in Oslo. Lunch at a vegan café led to an interaction with its bohemian clientele—a Johnny Appleseed world traveler/journalist in khaki jacket with dog, as conversation opener, focusing on his experiences in Bolinas and ecopolitics. Next I proposed next simply to use our Metro ticket and take a suburban tram to the end of the line, figure what to do when we got there. The tram emerged from underground after a few stops and wound its way upward through neighborhoods of modernist, sumptuous homes, with vistas of harbor and fjord ever more distant and dazzling in the June sunlight. At the top, elevation over 2000 feet from sea level, was nothing much except a viewing spot and a tourist attraction/educational site called “The Rose Castle. “

The café was still open, while the last visitors were about to leave for the day. This was the work of a utopian artist who wanted to start a conversation about, precisely, the unfinished work of reparation we had been questioning. Opposed to the stultifying narrative of the Akershus museum, this was something else—an attempt to broaden the awareness of participation in the Occupation, while deepening the account of its consequences. “The outdoor art project is dedicated to democracy, rule of law and humanism. It presents close to 300 artworks . . . that tell the story of what happens to a country when totalitarian forces gain control and subjugate its inhabitants to tyrannical rule, how society fights back, and how to bring the values of freedom into future generations.” The castle takes its name from the German Resistance group The White Rose, and was bit cosmic or spiritualist in orientation. As well, the original paintings of its founder—who had given up an artistic career in New York to give back to Norway—were a bit hard to take, however well intentioned. But we were informed by the novelty of the attempt, at least.

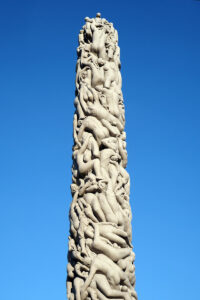

The third leg of the triangle was set: to overcome our resistance to the “must see” of all countercultural tourism, the Frogner Park (known to tourists as “Vigeland Park“). The sculptures are a work of world-transforming vitalism and perversity, accomplished over decades, by Gustav Vigeland. One has to wonder about the politics of this work, but also about its broad acceptance. The photo of Vigeland next to his work “reeks of Nazi mentality,” as a writer of the Resistance noted after Liberation in 1945; his work compares to Arno Breker. The sum total of the works depicts a fatalistic triumphalism of eternal themes that both raise the victors to the heights and cast losers to the dust; the Monolith at the park’s center most suggests a social Darwinist “cycle of life” with spiritualist origins. In one telling detail, “The Monolith was first shown to the public at Christmas 1944, and 180,000 people crowded into the wooden shed to get a close look at the creation. . . . The Monolith towers 14.12 metres (46.32 ft) high and is composed of 121 human figures rising

towards the sky.” Encountering the sculpture park in stages, through its entrance gates and along the series of figures on the Bridge to the Fountain to the Monolith, and on to the Wheel of Life, one has the feeling of a deepening fantasy that is at once being objectified in stone. A tension between material and ideal, both seen as fatal origins and ends, is everywhere imposed on the human form, which becomes enacted in ritualized displays of eros, aggression, community, alienation—one big image of the human condition, stylized in multiple versions of “the same.” Yet at the heart of this fantasm lies the irreducible fact of gender, male and female idealized as essences, and the

spawning of children, who may be wild or tame, as the result. A book on my shelf in critical theory titled Perversion and Utopia may advise—whose central thesis is that “there is an essential affinity between the utopian impulse and the perverse impulse, in that both reflect a desire to bypass the reality principle that Freud claimed to define the human condition.” And the site of this perverse utopia, its essay on the human condition, is in a park—the most popular in Oslo, where on a day in June families stroll and tourists take pictures of Vigeland’s monumental wish that life’s ultimate aim is to be cast in stone, despite (or due to) its passional basis. The magnet of the North begins right

here, with the vitalism whose ultimate source cannot be confirmed as either matter or spirit, darkness or light—possibly both—and whose aim is to come. What one can do is reflect on the aesthetic experience of viewing this work, which is a largely positive one if only by virtue of sheer astonishment. One may add that the Vigeland sculptures are without question sex positive, accounting for the lingering pleasure of many who view it.

Monday, June 12

SAS 1455 OSL > CPH

Hotel Ottilia, Copenhagen

A day in transit is a day subtracted from time. It becomes objective, to the extent that one can touch or handle it. What will we do with such a day? The route dropped away from magnetic North, pulled by the islands of the South. Along the route was a vacuum of a city called Copenhagen, within which was a nested space reserved for us. Unable to book an Airbnb in a neighborhood for only one day—it doesn’t matter which neighborhood, just so the needed assemblage of random impressions can take place—I bet the farm and booked at a boutique hotel in the former Carlsberg Brewery. Its unique design included a darkened hallway, even during daytime, where one found one’s way by means of a seductive series of lights. Various spaces were arranged to create an impression of slick intimacy, including the front desk with the rehearsed openness of greeting, to be repeated for each new

guest. The room was lit by a circular glass portal onto a courtyard of the old brewery, with a fountain and children at play being watched by their parents, some skateboarders nearby. Arriving mid day, needing to eat, we found the upscale restaurant seating hundreds with one table occupied, a foursome discussing development strategies it appeared. There was a stiff wind that ruffled the napkins, held down by a fork. “If you can tear yourself away from your room, head to the rooftop for a near-unrivalled view of Copenhagen’s fairytale rooftops.” The word rooftop repeats twice in this quote. Interested in the transformation of Carlsberg Brewery into a mixed-use, live/work, educational and cultural hybrid, I explored with camera. Some of the original buildings, as well as founder J.C. Jacobsen’s manor, remain intact, but most have been transformed in one architectural direction or

another. “PSST! Got a poor sense of direction? Look for the elephants! Hotel Ottilia is right next to the famous elephant gate in Carlsberg Byen—or look for the golden plates on the facade (they actually reflect the bottom of a beer bottle).” The beer bottle is an origin myth here. I took several pictures of the elephants, imperialist trophies adorned with transcendental swastikas (of their earlier, pre-fascist moment), trying to get the lighting right. Later we ventured out by bus to the city center, looking for an Italian restaurant with a measure of authenticity, which we found in Freetown Christiania, at a fabulous price.

Tuesday, June 13

Öresundståg train > Hyllie, Sweden

Skånetrafiken train > Trelleborg

FRS Baltic ferry > Sassnitz, Germany

Taxi > Glowe, Rügen Island

Boddenmarkt 1, Glowe

It was exciting to be in motion, in a timed delivery from origin to destination. For a measured period, there is an identity of being and becoming, if one were so to imagine it. Thus the goal is an equivalent to the sense of motion. That is why, waiting at a transfer station, looking out for the arrival of the ferry, or heading into the wind as the ferry traverses the Baltic, or standing on deck as it reverses engines and locks into the terminus, or waiting for a bus into town, one has the satisfaction of motion while standing still. That was the whole idea of spending several days on Rügen Island, a tourist destination of the former German Democratic Republic and, before that, site of the NS body-culture spa Prora, monumental barracks of the Kraft durch Freude program, publicized by the band Joy Division. Getting ahead of oneself is all right on Rügen Island, as time quickly slows down. It appears that my

reading of the map, and a German guide book from a previous visit, were all that was needed to find an ideal beach vacation rental for three nights in the retrofitted tourist area. The recently built vacation apartments, opening onto a courtyard with beachware and antique shops, ice cream stand, and fresh fish trailer across the road, were post-unification state of the art, in perfectly adequate taste—one might call it Ikea +, where the + stands for regional art/craft items added. The large apartment with many windows and doors onto decks, breakfast and dinner tables with umbrellas and barbecue, two bedrooms, sofa, and piles of linen was more than any two persons deserved. The entire ensemble seemed designed for quick removal of sand that had been tracked in from the beach. The Beach, across the main road and the vacation cottages from a former time, was at the far end a bit

sparse, rocky, clotted with seaweed, and broken up by pilings. A sign helpfully interpreted the omnipresent odor of rotting seaweed as part of a conservation effort, not to be disturbed. Despite the many small beach huts waiting to be rented, tourist season not officially on, the best option was to walk to the more sandy, less seaweed-heavy middle section, observing the curve of the bay all the way toward its endpoint at Kap Arkona, the lighthouse that gives the area definition and military significance. Something like the cultural milieu of the British TV series The Prisoner, an area charmed with “stubby, curious people,” as Robert Creeley wrote of the Belgian beach town Knokke, Belgium (and published in This 1). All over Europe, up the Atlantic and across the Baltic and Mediterranean, such towns proliferate and accomplish their socially important task of recreating the

work force so it may happily return to production. Such was the vision of the planners of the DDR, who offered these incentives mostly to the apparatchik elites, whose sons and daughters continue to come here. Many pleasant memories of socialism with a human face, visible in the modernist café-restaurant built some time in the 1980s and the still preserved iconic children’s rides along the boardwalk behind the dunes. We found a bit of time there, at the intersection of several histories that scarcely seemed relevant.

Wednesday, June 14

Thursday, June 15

Days collapse to become one day. There was something needing to get done that probably didn’t. This is a sense that could be extended for several weeks without complaint, but we were between points A and B, and this was the and. All of literature stands behind the right day to visit the lighthouse as endlessly deferred. But we would accomplish it this very day (likely the nordic impulse). Posted signs specify the pick-up and drop-off times for the bus, changing at Altenkirchen and proceeding on to Putgarten, from which we would walk the last mile to the lighthouse, given the lack of parking. The bus driver was notably surly and impatient—must not like his job. The lighthouse itself is not picturesque, though it holds down the coast: a hybrid of yellow brick cylindrical tower topped

with the main light, and a second light on a red brick building of lesser dimensions. The area surrounding is largely unimproved and is punctuated with disused bunkers, barracks, and maritime equipment from the Cold War period. At the time Rügen Island’s location in the Baltic was a crucial observation point for a mix of NATO, nonaligned, and Soviet traffic, both civilian and military. The effort to make it a tourist destination was thus, for historical reasons, a bit delayed though there was an attempt. It was hot and there were many weeds by the side of the road and in the fields. One trail led to a point overlooking cliffs that opened to the Baltic, but not much to see. In another direction one passed

the marked archeological site of a pagan religious cult, a raised mound covered in weeds, also not much to see. The trail kept back along the coast, an easy route under shaded protection to the fishing town of Vitt, which has been preserved. A few beached fishing vessels and a café, rocks forming a small harbor. The town’s buildings themselves are stubby and curious, one can imagine the independent fishing community that lived through the DDR. Up the road is a church that remembers mariners lost at sea, an apolitical trope, where candles are lit. The bus driver was asleep at the wheel at the Putgarten stop, waiting for his scheduled departure. He would drive to get anyone coming back from the lighthouse and then pick us up. Everything was closed because it was a Wednesday, but that was enough.

Another day to test the mechanism of deferral, which takes days to kick in. That is the opposite way of saying it—usually one says, It takes days to unwind. How to artfully defer to what, so that it comes out all right in the end—or does not, how would one tell? Writing itself could be informed by a mechanism of deferral, and often is (what is the stepwise plot of Russian formalism but a precise mechanism of deferral? So Shklovsky survived the Stalinist terror, knowing when and how to defer). But I digress. Walking the beach a second time, a more comfortable stretch was found, where shading the head by a book that was not being read was first invented. One might fulfill one’s future desires, such as lunch or a beer, later; this is the real meaning of “to each according to their needs.” The socialist-modernist beach café thus became a beacon of hope that

Kap Arkona failed to be. Here was a form of sociality that took some pleasure in itself—not a guilty pleasure but a stable, dissociated one. The lure of the commodity had not transformed it into the more unobtainable and expensive forms of restaurants elsewhere in Europe. A kind of wacky friendliness represents the vestigial socialism of a beach town in the former East Germany. One needs to factor that into account in making a historical judgment. The beachware shop, as well, sells items that continue the synthetic fabrics developed in the former managed market economy. Carla found a perfectly suitable linen dress to be worn a thousand times; the electric blue swimming trunks I needed were superior (more durable, better designed) than any to be had at REI. A picture postcard is a picture postcard, Stein could have written, it is a human universal. Warren Sonbert had sent us many

times from obscure locations he toured, many in Germany, where his work was highly prized. Now I am thinking about Warren Sonbert as I write, and the picture postcard. “The films of Sonbert’s mature period seem to contain multiple worlds . . . . While it is not always possible to grasp the exact psychological or emotional nuance he had in mind while constructing his ‘arguments,’ as Sonbert once called his films, their sensual appeal can be overpowering.” What neutralization or suspension of judgment does it require to find a postcard of Kap Arkona to be sensually present as a form of feeling? Extending that skill to multiple worlds was the discipline of travel Sonbert practiced. This account of blank leader that lights up a sequence of images is dedicated to him.

Notes and links

Images: all photos (c) Barrett Watten 2023; reproduce by permission only.

For travels in Iceland, see Magnetic North I here.

For Norway (Trondheim), Watten/Viken and Utness families, see Magnetic North II here.

For Berlin, see Magnetic North IV [t/k].