Friday, May 17

Delta 361 DTW > SFO

The Lab

Small Press Traffic

Hal Foster, Unseen

@ Et al. Gallery

May 17 is a triangular nexus in my calendar: birthdays of Lyn Hejinian, Kit Robinson, and Kathleen Frumkin, often celebrated with light remarks about page turning and celestial inevitability. Now that has changed, while the date remains as an index. On that date, Carla Harryman and I determined to travel west, to reconnect and make new connections, prompted by Lyn’s passing but multi-tasking as usual. File under “persons”: “Leaving tomorrow AM for one-week tour of the West Coast (San Francisco, Alameda, Berkeley, San Diego), focusing on people, the best kind of travel,” I wrote on Facebook. But “persons” are an index as well, to their activity and the contexts that surround them. Thus we encounter them.

Andrew Smith, for instance, was a person not known to me—but it was a fine meeting. In his role as director of The Lab, he is the custodian, as it were, of its history as well as current reinventor of its mission. Space and time: The Lab was founded, I read, 39 years ago, which I know as one of my first promising students, Laura Brun, was its cofounder. At the time I was teaching—I think for three semesters, but it may have been two—for the Center for Experimental and Interdisciplinary Arts at San Francisco State. My credentials were minimal: emergent poet and editor making an uproar on the San Francisco scene, represented by readings and publications—reputational capital enough for contingent appointment, though it would not last (I remember the day I turned in my keys and ID after my appointment was not renewed). Nor would the program itself. But its success, and mine, was the students, memorably Laura— while a number are visible on social media and are doing things in the arts. Laura was dedicated to the cause, and she put in her time getting The Lab up and running at a storefront on Divisidero Street. Among the start-up arts spaces from the 70s and 80s—Capp Street, 80 Langton Street, Project Artaud, ATA—The Lab is one of the survivors, along with Small Press Traffic; many others have gone down. And Laura, too.

while a number are visible on social media and are doing things in the arts. Laura was dedicated to the cause, and she put in her time getting The Lab up and running at a storefront on Divisidero Street. Among the start-up arts spaces from the 70s and 80s—Capp Street, 80 Langton Street, Project Artaud, ATA—The Lab is one of the survivors, along with Small Press Traffic; many others have gone down. And Laura, too.

The history of alternative arts in San Francisco is not yet written. The archives are there, but neither the narrative nor critical framework to expand on their significance. In that regard, one topic on our tour of persons and places was Renny Pritikin’s just-published auto-festschrift At Third and Mission: A Life Among Artists—which I brought up whenever possible, to gauge its reception in the field. What is innovative about this work is, in fact, its nontraditional form: an autobiography that has the feel of a curated exhibition, both site-specific and date-stamped. An exact number (52 sections, like a deck of cards) of thumbnail sketches of artists, exhibitions, and “meetings with remarkable men” (Einstein, Ginsberg), plus a coda to Bill Berkson, add up to a composite portrait of Renny Pritikin, curator of Bay Area alternative and museum venues—an index to more than the individual around which various aesthetics swirl. My topic is the person as index, of which Renny Pritikin provides a perfect example (like the Poetry Baseball Card on my shelf for Ron Silliman). There is a synergy, thus, between the fractal form of alternative arts spaces and a composite portrait of the curator-as-artist, as an interpretive frame. But there are others, both in and out of that frame. Here it was significant to gauge the reception of this “portrait of our time” in terms of those who were there as well—equally active, equally productive, equally important. These ranged from bland appreciation of a well-turned career (e.g., a Hyperallergic review) to outright rejection (“not the most interesting art”) to nuanced critiques of what was left out against what was claimed. Certainly I know, and can testify to, much of that—as we will see in due time.

Here is an aesthetic of the curator certainly, but relying too much on “the touch.” There is barely a nod to the collective production of art in the period, the interlocking scenes that make each example what it is, as well as the boots on the ground. What we get is an economy that was all too evident at time: the way “representative” figures were chosen to stand for the whole. “The names of history are retrospective,” perhaps, but they are not fixed in time. Time is an index determined in its various unfoldings, beginning with the present, but it certainly does not end there. This leads to the concept of “reception history,” one I employ frequently and take for granted for its usefulness; it organizes my thinking in many areas. It is not obvious, however, as I found when explaining it only yesterday to a friend over lunch. There is the “horizon of expectation” of a given kind of work (the novel; the lyric; Language writing); then there is the historical framing that makes sense of the work, the author, or the movement. There is a Shakespeare for each century and a Gertrude Stein for each decade. What will be said about alternative arts in San Francisco after the period of their emergence, development, dispersion, sometime collapse, and retrospective? The image of Berkson as coda to Pritikin’s volume is precise: the ultimate survivor, Bill’s will to live was part of his merit as a poet. When he is read, his work will disclose the aesthetic assumptions of that will. Pritikin curates this connection but does not explain it. And why should he? The practice of survival is an intimacy like no other. Books are written to mask and disclose it.

My theme has shifted a bit: from the index to survival, on which an index depends. What will survive of art, poetry, or the worlds that produce them? This is part of a larger question—the nature of art’s (or writing’s or community’s) value, which I have been obsessed with in recent days. Thus it is important to estimate the on-going labor of value production in Small Press Traffic’s project to archive the poetry scene, from the 70s to now, and make it publicly available. This is even more urgent as its near namesake, Small Press Distribution, has just gone down, leaving a gigantic hole in the security blanket of poetry. Cartons of books are being taken to dumps and incinerators as you read online; this is no light matter. Pushing back against that destruction, Small Press Traffic is inviting contributions to fill in the blanks of Bay Area poetry history, which they plan to house in a small but efficient upstairs back room of the Et al. gallery and bookstore on Mission Street. This positivity is a curative to the many ills that have plagued the poetry scene of late—sectarianism and calling out, discouragement and back-biting; one has seen or heard it all. A persistent task of my travels, I confess, was to flush out and address this recent history, particularly the online hit pieces that, I am told, were produced by someone in Bay Area poetry. In refusing exclusionary logics, Syd Staiti is taking the correct road toward the good of all. Insofar as there may be exclusions, they cannot detract from the value of the larger history, of its many actors. Otherwise put, it was nice not to be shunned when I walked up the stairs.

A person is a positivity—unlike the subject (of language, of history), rifted by the negative. I recall when Language writing was supposed to “do away with the subject” and replace it with language, quite a radical move. One bridge in the cantankerous relations between Language writing and New Narrative may be the “person” as not merely reducible to Language. A bridge that was, to begin with, a two-way street: Language writing freed up what counted as “the person” so that various genders and sexualities obtain. Or, put another way, Language reconfigured the present metaphysics of the New Americans toward a construction of the subject. That did not predict which subject would be constructed; after Judith Butler, this is a historical question. There are many such types of person (a return to the index, perhaps). Megan Adams/Camille Roy certainly presents herself as a “person” as positivity, even as she leaves room for the indeterminate by virtue of the /slash. Which is also to say, any one of us are “person” in that divided yet constructed sense. This recalls the issue of Poetics Journal Lyn Hejinian and I produced in 1992, with its cover was John Woodall in the distressed guise of a “person.” And where is John Woodall now, along with his legacy for Bay Area performance art? The visit with Megan/Camille took place in the present; an early summer breeze with traces of fog rifling the shrubbery on the back of Potrero Hill as celebrity tea was served. In the course of the conversation it was disclosed that we have common roots in the Nordic—as Megan/Camille insisted, genetic material is not clearly divided between M and F, though mine is 50% I am sure. Her locus of ancestry is no less than the tip of the Lofoten Islands, a unique place that brought to mind the “high value” of information theory. It is definitive of personhood to descend from such a place; it is the necessity of such a person to return. My newly discovered ancestry dates from the eleventh century in Trondheim, of no less high value or specificity, by which I am compelled.

A person is a positivity—unlike the subject (of language, of history), rifted by the negative. I recall when Language writing was supposed to “do away with the subject” and replace it with language, quite a radical move. One bridge in the cantankerous relations between Language writing and New Narrative may be the “person” as not merely reducible to Language. A bridge that was, to begin with, a two-way street: Language writing freed up what counted as “the person” so that various genders and sexualities obtain. Or, put another way, Language reconfigured the present metaphysics of the New Americans toward a construction of the subject. That did not predict which subject would be constructed; after Judith Butler, this is a historical question. There are many such types of person (a return to the index, perhaps). Megan Adams/Camille Roy certainly presents herself as a “person” as positivity, even as she leaves room for the indeterminate by virtue of the /slash. Which is also to say, any one of us are “person” in that divided yet constructed sense. This recalls the issue of Poetics Journal Lyn Hejinian and I produced in 1992, with its cover was John Woodall in the distressed guise of a “person.” And where is John Woodall now, along with his legacy for Bay Area performance art? The visit with Megan/Camille took place in the present; an early summer breeze with traces of fog rifling the shrubbery on the back of Potrero Hill as celebrity tea was served. In the course of the conversation it was disclosed that we have common roots in the Nordic—as Megan/Camille insisted, genetic material is not clearly divided between M and F, though mine is 50% I am sure. Her locus of ancestry is no less than the tip of the Lofoten Islands, a unique place that brought to mind the “high value” of information theory. It is definitive of personhood to descend from such a place; it is the necessity of such a person to return. My newly discovered ancestry dates from the eleventh century in Trondheim, of no less high value or specificity, by which I am compelled.

Bob Perelman

Francie Shaw

Norman Fischer

Kathie Fischer

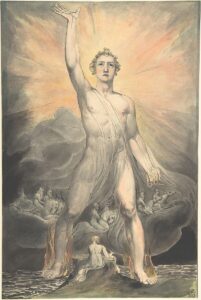

A “person” is a piece of work—maybe a better way of putting it than “constructed.” It is part of their survival strategy in the long run. We start down the road on equal footing, with a normative set of capacities, but then are built up in asymmetrical ways. Imagine the “will to live” of Bill Berkson as one of the central dimensions of his “person.” Was this his symmetry or asymmetry, and how could one tell? Here I think of William Blake’s watercolors of the “person” in their visionary aspect, and the use of “symmetry” he deployed. But as I learned from my tutor in Blake studies at Iowa, John E. Grant—a study in uniqueness in his own right—it is of the highest importance whether figure drawn by Blake is extending his right foot or the left, or raising the right arm to the heavens, as here. We are asymmetrical, and that is part of our value—but how much of it will survive? This a passage, from an online memoir, sums up my experience of Grant as “vanishing mediator” of Blake:

A “person” is a piece of work—maybe a better way of putting it than “constructed.” It is part of their survival strategy in the long run. We start down the road on equal footing, with a normative set of capacities, but then are built up in asymmetrical ways. Imagine the “will to live” of Bill Berkson as one of the central dimensions of his “person.” Was this his symmetry or asymmetry, and how could one tell? Here I think of William Blake’s watercolors of the “person” in their visionary aspect, and the use of “symmetry” he deployed. But as I learned from my tutor in Blake studies at Iowa, John E. Grant—a study in uniqueness in his own right—it is of the highest importance whether figure drawn by Blake is extending his right foot or the left, or raising the right arm to the heavens, as here. We are asymmetrical, and that is part of our value—but how much of it will survive? This a passage, from an online memoir, sums up my experience of Grant as “vanishing mediator” of Blake:

A good deal of Jack’s work will vanish, however, not because of the quality of the thought that went into it but because it is written in the margins of papers and books, in letters, and, most famously, on museum postcards . . . . Even if one were to preserve Jack’s private correspondence, most of it wouldn’t mean very much to anyone other than its recipient, and even the recipient might struggle to keep up with the densely allusive sentences packed into a Grant missive . . . .

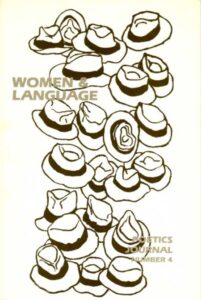

I met Bob Perelman at Iowa, the year after I took Grant’s seminar in Blake’s illuminated books—and wrote an analytic outline of his “Milton,” to his withering critique, which survives in my archive. Grant was also not impressed that I dropped the name Northrup Frye in his office hours; his was the polar opposite of any totalizing view. Thus, some time later, reading Ginsberg’s Indian Journals, I might wonder whether it was the vision or the particulars that moved. This is not to digress: what was in the air of the early 70s was a “fights war,” per Ginsberg, moving away from holism to particularity. Bob seemed to be on the side of both: his early work Braille tried to particularize holism, not an easy trick for a cowboy riding a roiling psyche like Bob’s. It was a period concern, and Francie Shaw, together with Bob, also was interested in taking on holism and symmetry in her figurative work, as we see in t he cover of Poetics Journal 4, in which the Symbolic Order is deconstructed into gynocentric hats. All this registers the specificity of “the person”—and there we were, four of us, sharing a table. Francie’s recent work to rethink Classics Illustrated, exhibited at Small Press Traffic to much notice, was a singular presence (here). For the meal I recall an artfully prepared Salade niçoise with tuna of the kind one can only get at Berkeley markets. On the other side of the table were two prodigious “persons,” Norman and Kathie, embodiments of what presence can mean now that it has been detached from any preexisting absolute. “Walking on water was not built in a day,” as Jack Kerouac said, but their method is to veil the immense labor to become present as a value realized in the present. What kind of work does one do to become present, and should it be calculated with wage labor placed in exchange? We are fortunate to live on the side of the immortals who have figured that out. Blake certainly was one of them, but then there are many ways to read Blake. I am not digressing. It was a lovely time with friends; you should been with us around the chowder pot.

he cover of Poetics Journal 4, in which the Symbolic Order is deconstructed into gynocentric hats. All this registers the specificity of “the person”—and there we were, four of us, sharing a table. Francie’s recent work to rethink Classics Illustrated, exhibited at Small Press Traffic to much notice, was a singular presence (here). For the meal I recall an artfully prepared Salade niçoise with tuna of the kind one can only get at Berkeley markets. On the other side of the table were two prodigious “persons,” Norman and Kathie, embodiments of what presence can mean now that it has been detached from any preexisting absolute. “Walking on water was not built in a day,” as Jack Kerouac said, but their method is to veil the immense labor to become present as a value realized in the present. What kind of work does one do to become present, and should it be calculated with wage labor placed in exchange? We are fortunate to live on the side of the immortals who have figured that out. Blake certainly was one of them, but then there are many ways to read Blake. I am not digressing. It was a lovely time with friends; you should been with us around the chowder pot.

A “person” is a construct or piece of work, so one comes to be. This is an artful accomplishment, toward which my sister Jan has found her way in the pursuit of the visual image, mediated through photography. Carla and I returned to her place, where we sat around and spoke of the fall of empires and other topics too portentous to name. Her recent return to our family history in Taiwan offers a personal account of our construction, which I cannot fully take up here. It is resolved in the present, which was where we were, taking it lightly. Her household, in any account, is an index of family and travel—images and things bursting at the seams, each displacing the other but demanding their own attention (as particulars). Jan’s recent travel work borders on magnificence, as in an example here. So we imagine anything is possible in a given day, an index extending outward in time.

A person might also be an absence, someone not there. This travel writing began with and is dedicated to the memory of Lyn Hejinian, whose use of writing of all kinds encompasses the genre.

Notes

Images: BW, Syd Staiti and Carla Harryman, San Francisco, 17 May 2024

Anon., photo of Laura Brun and daughter, n.p., n.d.

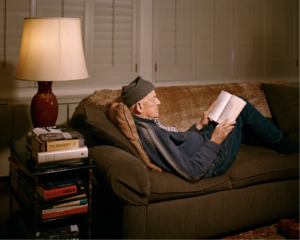

Doug Hall, Bill Berkson Reading Dante, from Renny Pritikin, At Third and Market: A Life Among Artists

John Woodall, [title t/k], cover of Poetics Journal 9, ed. BW and Hejinian (1992)

William Blake, Angel of the Revelation (Book of Revelation, chapter 10)here, 1803–5, The Metropolitan Museum ()

Francie Shaw, [title t/k], cover of Poetics Journal 4, ed. BW and Hejinian (1984)

Jan Watten, Taroko Bay Film Capture (2024), online