The photo registers the scene: it is Ron Silliman reading, Krishna Evans following the text. Or perhaps Krishna is reading and Ron is following the text, as will be the case in a minute or two, as soon as Ron finishes his passage. The vantage point is from where I am sitting, having read my part some time ago and now listening as it continues. To the side are Eliot D’Silva next to Ivan Sokolov; then to the right are Jen Hofer, leaning against the garage; Claire Marie Stancek is just behind the forked trunk of a tree; Jennifer Scappettone between the branches of the tree, and Jane Gregory, the host of the event, is to the far right. Continuing out of the picture one would encounter Lytle Shaw, whose elbow is just visible, and then next Syd Staiti on the stairs. Everyone is not especially solemn but bent to the task, reading Lyn Hejinian’s just published Fall Creek (Litmus Press), copies and xeroxes of which are out on the table. All of them have taken their turn. There are thirty-three sections, with Ron and Krishna reading the next-to-final two, before the group takes up the last section in unison. This was my proposal to the group at the break, recalling the pleasure of cacophony in our Grand Piano reading of “A”–24, whose plurivocality Lyn internalized and, some decades later, realized in one of her last works.

Fall Creek is a series of linked improvisations that push the unfolding of phrase and sentence, informed by the habits of careful description and the radical freedom of free jazz. In that sense it is a kind of aesthetic combine, Lyn’s daily practice of observation meeting the total freedom to take the possibilities anywhere. At the memorial (the event to come) I described the unison reading to Larry Ochs as akin to Ornette Coleman’s epic Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation (1961), which our entire generation had heard and internalized but scarcely know how to achieve it. Two four-person ensembles playing against each other to create a kind of time that neither one could have made alone. That freedom was aspirational: the legacy of the 60s carried over to our period of emergence a decade later. By what means to realize it? The next perception must have been, in a kind of epochal phenomenology, that there was a disconnect between freedom and the daily experience of living in that time. The turn to “everyday life” and its critique happens right there: between the dialectic of liberation and the clock time of quotidian events. Our route to that freedom through Zukofsky now seems like a sidebar, as there were others in the radicality of Poets Theater too: here a cunning of aesthetics, seen in its historical emergence. It took a few decades of politics to fully engage it, along with some personal resettings of the dial. Lyn’s work after the millennium embraces the critique of everyday life, seeks to enact and prolong it. The result is what we were, in unison, reproducing. It is a critique of everyday life as a condition of collective freedom, if only for a minute.

But there is another kind of time, as well. I see it in the granite or stone sundial or bird bath, right in front of Silliman’s tennis shoes, filled by a collection of small succulents. The unmoving pole around which the temporalities, multiple voices, swirl. This was a memorial event, but carefully not the official one—that would come later. It was ad hoc, elective; you could be there or perhaps had other plans. One way or another the event would take place and convey precisely what it was. This was a fundamental premise of all of Lyn’s work, circling around an absent but known center. Such as the memorial event that we, and many more, would participate in a day later. Carefully planned and staged, with a program of family and poets, projected photos and high-end musical introduction (Olivier Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time [1940], written in a concentration camp no less; you can listen to it here), an interlude with Rova Saxophone Quartet minus One, and the final stunning video of Lyn reading—this was a kind of time out of time, which never happens until it does, and is still not an exact equivalent to the fact of Lyn not being there to take part in it. I was charged to be present in this time, a deep honor of course. With the stipulation that it should be no more than five minutes, with few introductory remarks. What does one do with 4’33”, John Cage might have asked? I read the denouement of my long poem Notzeit, as a thought experiment on the continuity of Lyn’s life and work. I did not refer directly to her but framed the poem through Gertrude Stein’s notions of beginning, middle, and end. Lyn celebrated beginnings as part of her late style. Everything was skewed by a consistent readability as the middle of her work—circling again, around the experience of not there.

I decided to wear a tie—no one else did. I don’t even know if that was me up there. As Larry commented later, “We did what we could”—it was an outpouring of people trying very hard to do that. Others were eloquent, moving. Or not—the displacement is equally the point. To whom am I speaking on this occasion, thus? Everyone felt that, but it was not the point. People say the damnedest things at wedding and funerals: it is because they are no longer know who they are. Norman Fischer’s role setting the tone for the event commented precisely. One ritual I like very much in Buddhism is the setting out of a small photo or even name card as a memorial for the person not there. It really doesn’t need to be, can’t be, more than that. The most grandiose induction into the Hall of Fame, the Pantheon, or the Land of Dead does not amount to much else. André Breton begins his life-affirming memorial of Nadja at the Hôtel des grands hommes, on the courtyard outside the actual Panthéon, in a moment of supreme irony that is displaced, in the text, by Nadja’s minute handwriting and napkin drawings. Nadja is, in my reading, the beginning of the Critique of Everyday Life, and thus I have compared it to Lyn’s work at a crucial juncture of its coming to meaning in form. We all were a part of that, too—throughout The Grand Piano you will find the critique of everyday life as a part of recording itself. That was its meta: a condition of writing as the event.

I have said something about this event, the one we intended and fulfilled. Almost to the side would be its approach in the group reading, then the “return,” as it were, to some kind of normal time. For that purpose we found ourselves traveling up the North Coast for several day’s retreat, then back to Detroit and its brand of amnesia. The interesting difference is what it has felt like since then. Something has been taken away, cannot be restored. It is a subtle shift. It has its own time. I am sure many are feeling this in their own ways. I am putting a marker here in place as a kind of record. Soon I will return to my account of what happened next, but this is enough.

Notes and links

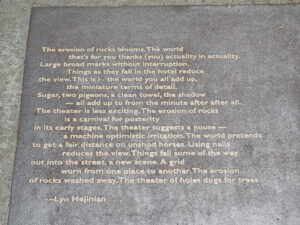

Images: group reading of Fall Creek by Lyn Hejinian, home of Jane Gregory, Oakland, 13 July 2024; presentation at Lyn Hejinian Memorial, 14 July; Lyn’s poetry installed on Addison Street, Berkeley. Photos: BW and Carla Harryman