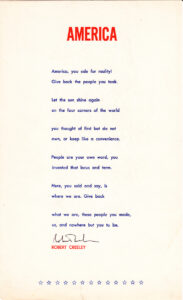

For the thousand manifestations that dotted the American landscape yesterday, I want to post this broadside poem by Robert Creeley. It has always seemed a kind lurching effusion of a politics, a consequence of the state of mind he wrote it in without doubt. Creeley was often convulsive, and that is to the point of his aesthetic, even concerning details. But here the subject of his “attack” in William Carlos Williams’s sense is broad, vast, gestural, involuntary. It is worth remembering that much poetry that followed shelters in the shadow of that attack. Thus it bears some comment at a later moment, as late as the one we are in, where the poem resonates anew.

Everything hinges on the word “people” as constituting and yet denied by “America.” This a poem of a split moment that was understood in one way at the time of its writing, the late 60s, but has continued until now. With each increment of its elaboration. Who are “the people”? They must be everyone who “we are,” but who is to name them? That would be the job of “America” as a name—arbitrary enough, but there is no outside beyond it. We are in a kind of circular crisis between “America” and “the people,” with nowhere to stand. The division itself must be us. If we have any hope at all of solving the riddle, we must push ourselves to the outside.

Such was a dream I had the other night. I was dreaming to try to be awake. It was an impossible task, like surfacing from the fluid depths of a pool whose surface one cannot see, because one is not outside it. The surface, looking up at it but unable to break through, was a kind of mirror reflecting the face of an aspirant turned upward. The body wants to liberate itself from sleep but is caught in the reflection of its looking upward, which can only be reflected back. As the body approaches the surface of its desire to break through, the resistance increases exponentially. It is paralyzing, explosive on the other side. The desire to break through can only be convulsive.

“The people” speak to their mirror image, “America,” wanting to break through. I have always wanted, from an early age, to be outside that restrictive boundary, on the other side of which is a difficult freedom. The freedom of breaking through. I could not force myself to break through that surface, could not wake up. Thus we are caught in the nightmare of the external limit imposed on us, “America,” pressing we “the people” down. We demand: “Give back the people you took”—whom you have alienated. What would follow would be general liberation: “Let the sun shine again / on the four corners of the world” this nightmare would deny and oppress.

Creeley’s poem is convulsive beauty. It is always the feeling I have had in a large crowd, arguing the injustice of the situation and the limits we have been placed in, the false name for us that has been given by them. I have only passion in that moment. When it recurs, I arrive at a self-understanding that can only be given, when I take myself back from this falsehood. This is the situation we are in at present: a nightmare of not being able to awake reflecting back at us. Every slight indication—Creeley’s lurching poem to declare independence—is a return to that cycle. But there is no outside; there is only a deeper knowledge of the situation we aspire to give a name.

Note

Robert Creeley, “America,” published as a broadside by Black Flag Raised, 1970; first collected in Pieces, 1969.