Monday, June 21

Delta DTW > LHR [canceled]

Carla Harryman

What does it mean to travel? And what are the risks? You could hit an iceberg, for example. In this age of global devolution due to war, pandemic, climate change, and supply chain disruption, the risks are increasing. The magic “reward miles” that purchased at least one ticket were offset by ambiguous reentry requirements and increased insurance costs. Our awareness of global supply chain disruptions came with the brutal cancellation of our fully boarded flight. The air conditioning had heated up, needing to be replaced; the parts were in Atlanta, but no means to get them to Detroit; by the time they would arrive, crews had to rotate; no additional crews were available. By the time this was decided we had wandered the Detroit airport for some hours, only then to be automatically rebooked. The gap in expectations was predictive: this would be no easy trip, but still worth the attempt, we believed.

Tuesday, June 22

Delta DTW > IAD

Virgin IAD > LHR

Refreshed by an extra night of sleep before departure, we renewed the attempt. Now we are less concerned with global supply chains, as the aviation network is algorithmically rebooted to our advantage. Now it is a question of mask behavior and the algorithms of disease transmission. Universally, or in the metropole, the “unfulfilled democratic demands” for global travel had become a surge of pent-up consumerism; with the release from austerity, as a form of repression, off came the masks. They were no longer required to board a flight, nor were negative test results required for readmission, at least for passport holders. The politics of the New Normal are us. Willingly confined to our cubic meter of seating, we endured the deprivation of freedom as a contract with global mobility. One flight took us to the sterile, remodeled Dulles Airport, with many murals of JFK, and then onward to Heathrow, on an airline named for the “Virgin Queen” during the heydey of Thatcherism.

Wednesday, June 22

189 King’s Cross Road, London

“Surrealism Beyond Borders”

@ Tate Modern

Our trip was structured around several agendas: for me, catching up with global exhibitions, literary friends, and Berlin; for Carla additionally, a launch of Cloud Cantatas, published by Pamenar Press and delivered that very day in London. After presenting at last November’s virtual conference on surrealism, I had wanted to get to the New York version of the show before it closed in January at the Met, but omicron put an end to that. The Tate Modern was the next venue, the monumental showcase for New British Art responding to the global, decolonial imperative. To what extent this exhibition truly understood or could identify the theoretical horizons of the global dispersion of surrealism was, however, in doubt. Static art-historical orders of style and periodization remained in place, tending toward inadequately framed concepts of history and space. There were groups of painters in Mexico City or Cairo, for example, who carried on the tradition of group activity in surrealism. But what could be seen of the decolonial moment, precisely the moment of surrealism’s global dispersion through emigration and emulation after 1945? There was not nearly enough education on postcolonial liberation, not enough hard connection between the “inner” liberation of surrealism and the politics of liberation as a post-modernity. That said, there were many revisionist moments to be explored: the rise of an African-American “demotic” surrealism with Ted Joans, Amiri Baraka, and Bob Kaufman, for example; or the anti-Eurocentric contributions of second-wave women surrealists, from Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo to Claude Cahun, Maya Deren, and Ithell Colquhoun, not to mention Lee Miller and Dorothea Tanning. But this was still surrealism as art history, alas. The lesson for global exhibitions is to radically contextualize the exemplary work in an unfolding horizon of global negativity—a globality that is not one thing.

[not Jonathan Skinner]

[not Robert Hampson]

Pamenar Press book launch

Candid Gallery, Angel, London

Carla Harryman

Ghazal Mosadeq

Emma Gomis

Andrea Gomis

Philip Terry

Peter Jaeger

Jèssica Pujol Duran

Tim Atkins

Amanda Allen

Jeanne Heuving

Our plan also was social, to leave enough time for seeing people apart from events. I wanted to look up Robert Hampson, whom I had last seen, I believe, at his 50th birthday party at a pub on the Thames, which we identified crossing the Millennial Bridge from the Tate. Jonathan Skinner thought he might join us, as well, but the problem was the recent heat wave, alternating days of rail strikes in the U.K., and academic overload after the translation conference in Wales, which many had attended. So we went straight from Heathrow Express to an airbnb near King’s Cross to process the art, followed by a quick change and the Pamenar Press book launch for Carla. What united the various readings was an intersection of language and performance, highlighted in Emma Gomis’s Q&A dialogue with Anne Waldman and Peter Jaeger’s handmade New Sentence recitations of negativity. That negativity was earned, I heard in detail later, by the forced redundancy of creative writing faculty at Roehampton University, for which my true sympathy. After Thatcher, the U.K. has led the way in the humiliation of arts and humanities. Carla’s Cloud Cantatas were a perfect demonstration of “inner” and “outer” in the duration of pandemic, I would say, having lived with her during the time in which she wrote them. An after-party followed at an upstairs café, with poetry talk and licentious amusement carrying on for hours. It seemed like just the thing we should be doing. Carla was surrounded by women interested in her performance and craft, and I kept my end of the table from crashing. It was a fine opening to connections of all sorts, a harbinger of creative destiny as one might imagine it.

Thursday, June 23

Bedford Hotel, Southampton Row

Cornelia Parker @ Tate Britain

Penny Goring, Penny World @ ICA London

A quick decision was to extend our stay in London by a day; less than 24 hours would be extreme, after the flight cancellation that started things off. London was looking good with a string of cloudless, temperate days following the first summer wave of heat. So we booked a moderately fancy hotel for the night, hoping to bill the airline later. The days’s object was Cornelia Parker at the Tate Britain (the old Tate, with its permanent collection, Blakes, and Turners). Cornelia Parker, along with Rachel Whitread, are breakthrough women artists of the 90s and feature, for their sculptural logics of destruction and trauma, in the later sections of Bad History. Reparation, in the tradition of Melanie Klein, entails prior destruction of the object that repairs; Parker is aware of this tradition and, in her work, claims it as British, interpreting a history of class war, sexual violence, and postindustrial decline as metanarrative for what it means to be British. Hence Tate Britain put her on: perfect. My first response was that she had almost achieved the Holy Grail of rendering art as purely material, the quest of multiple artists after 1945, referring directly the material destruction of the war. But, at the same time, she deftly interprets each material strategy through an enabling “anecdote,” something like the opening frames of Foucault or the New Historicists. In one example, the first major work in the show, she writes, “Drawn to broken things, I decided it was time to give in to my destructive urges on an epic scale. I collected as much silver plate as I could from car-boot sales, markets, and auctions. Friends even donated their wedding presents. All these objects, with their various histories, shared the same fate: they were all robbed of their third dimension on the same day, on the same dusty road, by a steamroller.” Hovering over her material strategies, then, is an artful narrative that could be seen as an object in its own right—a dissociation of the purely material into an equally linguistic element. I feel I am in Pig Heaven with this work, one carefully destroyed and annotated piece after another, leading to larger questions of public art, social justice, and a conundrum of Island England, the common destiny of its inhabitants to be renewed as national iconography after all is said and done: “The chalk from the White Cliffs of Dover has figured significantly in my work over the years. I love it as a classic drawing material and its role as a patriotic feature of our coastline. It literally marks the edge of England.” I too am moved by the White Cliffs of Dover as the edge of England, but am starting to sniff out the funding structure. The gestures of placing Parker’s work throughout the permanent collection, which it enhances but takes value from, and finally her use of the backings of Turner paintings as material sculpture that she sells back to the museum, brings her England back to the brutal business of primitive accumulation, extracting value from the materiality of labor, and not ironically. So the narrative sets, regardless of her strategy to elicit affects of repair out of destruction. We would like to have lunch, followed by a walk along St. James Park, with its British collection of trumpeter swans, to the ICA, where in years past I have seen compelling art. This week on view are the regressive, childlike drawings of Penny World, another legacy of Melanie Klein perhaps, which even the ticket taker could not recommend. So I pick up a copy of Cosey Fanni Tutti’s autobiography art sex music as a trophy of the British paperback trade, as my revenge.

Anthony Joseph

Jeanne Heuving

Book launch for Anthony Joseph

Café Oto, Hackney, London

Because I have not been getting to London enough, I had never been to the Oto Café—legendary venue of out jazz improvisation. Jeanne Heuving, in London for a week as the centerpiece of her residency at Cambridge, which was otherwise cut short by COVID, invites us out to hear Anthony Joseph. I was first introduced to Joseph’s work through Lauri Scheyer’s essay in Diasporic Avant-Garde, presented at our conference as far back as 2003. Outside the venue was the man himself, and I introduced myself and recalled that project. He credited Lauri, and I believe her essay, with total gratitude as helping him in manifold ways through his career. I am moved as well, as Carrie Noland and I sweated bullets to get that volume to print, which finally happened in 2009. “Diaspora and Avant-Garde in Contemporary Black British Poetry” is the title of Lauri’s essay; I dwell on this as quite often one thinks what one does in the trenches of publication is simply cast out there, never to return. Now it is 2022 and I am having a pleasant conversation with Anthony before his event, for Sonnets to Albert, a sonnet sequence in memory of his father but also to lineages and parenting between Trinidad and the U.K. In the Q&A, I ask something that in retrospect seems academic, about Claude McKay’s use of the sonnet, and get a citation from Frantz Fanon on colonial mimicry in return. Then we break and come back to hear a consummate performance of the sonnets and improvised jazz, a combination one may not have imagined. Then to a dive bar around the corner in Hackney, by the name of Speakeasy, dirt floors and earrings, where the sea bass is quite good and the IPA is American.

Friday, June 24

Eurostar London St. Pancras > Paris Nord

41 rue Beaumarchais, Paris

[not Abigail Lang]

[not Hélène Aji]

[not Benoit Bondroît]

[not Olivier Brossard]

[not Simone Fattal]

The shift of one day from our original plans was consequent. If such can occur on a local, personal level, imagine such consequences on the global supply chain. We had hoped to reconnect with everyone involved in our visit to Paris in November 2021, with readings at ENS and Nanterre and a whirlwind of poetic activity, and before that the loss of Etel Adnan and time with Simone Fattal. Immediately subsequent came the onset of omicron, leading to the fourth wave (or was it the fifth?) with its attendant spike in mortality. Perhaps a dinner could be arranged, and some work on translation advanced. Academic exhaustion for those who teach, the difficulties of getting in to Paris and/or the desirability of getting out of it and the upcoming conference on American poetics the next week raised the bar of contingency. Travel cannot be guaranteed in advance, despite all plans. We were a global supply chain, interrupted. Out of the gaping maw of the channel tunnel, past maskless crowds and security screeners, we arrived nonetheless.

Françoise de Laroque

Toyen, l’écart absolu @ MAM (Museé d’art moderne)

Once arrived in Paris, we would not miss a thing. This is a universal sentiment, long before Enlightenment. The chain of locks over the Seine in the City of Light. At the Musée d’art moderne, Avenue Président Wilson, we met our friend Françoise for the major retrospective of Toyen, whose work til now has been a footnote to surrealism, now in a process of expansion and revision (as above). Toyen is perhaps the foremost of modern artists to have understood themselves as nonbinary (with Claude Cahun) before the term existed, through their use of the gender-ambiguous name (modified from citoyen) and the eschewal of feminine inflections. Toyen performed gender on the faultlines of the automatic image, aligning gender fluidity with surrealist liberation, depicting sexual revolt in multiple forms. As is well known, heteronormative blindspots proliferated in the surrealist movement, with André Breton as prime offender (see the 20s debates in Investigating Sex), though he supported Toyen without reserve in later decades. The evidence of the work is a window on liberation as a refusal of fixed gender identity, enacted by Toyen from the onset of their becoming. I left the exhibition with a new touchstone in place, pausing in the museum store for work by another surrealist, Benjamin Peret, whose work may be seen in like terms of species-boundary transgression, particularly his Histoire naturelle. In museum culture, the emergence of these artists still conveys transformative potential. We then visited the aforementioned chain of locks, follies of bondage and freedom, finding our way to a dusty café. On the bus up to Montmartre, in continuing amiableness, we passed again the giant apple of Fourier.

Saturday, June 25

Linda Watten

Pride Paris/Marche des Fiertés LGBT

[not Pina Bausch @ Théatre de la Ville]

A visit with my cousin Linda, temporarily at l’Hôpital Cochin, was the day’s primary mission. Bus reroutings, for a reason to be disclosed later, were the first obstacle to overcome. With a shrug of the shoulders a band of passengers would head for the nearest Métro. I have been coming to Paris on a yearly basis for some time, and can no longer be considered a tourist. How long can that continue as global temperatures and demand for carbon-neutrality rise? My cousin Linda, an expat from the US to France since the 90s, settled this issue with her act of decision to move. As Robert Creeley would write, “The card which is the / four of hearts must / mean enduring experience / of life. What other / meaning could it have” (“Numbers,” from Pieces). Over the past several years I have found a way to meet Linda in Burgundy, Paris, New York, or Amsterdam whenever the opportunity permits—as soon as you touch down on the continent, she would say. Masked up, nous sommes ici pour visiter ma cousine, we were welcomed by the hospital staff on break. We discussed books, leaving a Chinese novel in translation and a recent memoir of the war in Ukraine. All seemed to be on track and we would visit the next day. Again we were diverted by errant buses, finally heading to the Place des Vosges and Maison de Victor Hugo, where a small display on a Ukrainian epic hero of the age was advertised. Genuinely admiring the rooms decorated with orientalist wallpaper, I was inspired to further explore Hugo’s Eurocentric horizons in his Orientales, which every schoolchild in France must have read by the age of twelve. Ukraine wants to be part of Europe, but at the time was a liminal space bordering on the steppes. After cold white wine at the Café des Vosges, we headed out of the Marais to meet a roaring demonstration of many thousands of people, filling the boulevards and making tons of noise. This was the cause of our detours, Paris Pride—which we cheered from the side as we liberated pixels. We were unable to attend Pina Bausch that evening due to COVID, but later that night went out to look for the best whiskey bar in Paris, which we found: the Sherry Butt, which means that the single-malt whiskey is aged in casks originally used for sherry, and is very expensive.

Sunday, June 26

Linda Watten

Françoise de Laroque

/ Germany / 1920s / New Objectivity / August Sander /

@ Centre Pompidou

Librairie des Abbesses

Librairie Anima

We visited again first thing the next day, but there was need for caution as we had been out on the street with thousands of revelers, on buses and the Métro, in crowds at museums and social gatherings in bars: the onset of the Fifth Wave. Masks stayed on tight, while the hospital staff was cheery as ever in the break room. My cousin Linda is possibly the bravest person I know in the face of adversity: “a natural and prompt alacrity I do find in hardness,” as another character said in an unlike context. The roots of character are not given, I claim, but a composite of many influences, with a unique result. For Linda this is what is meant by modernism, which she finds in her readings of Beckett, Ashbery, and Perec. We talked books until it was time to leave, and hoped she would get out of there soon. Our next appointment was with Françoise, whom we would meet at the remodeled Beaubourg, always the people’s house of art. On display was a capacious revisionist account of the Weimar period, from the New Objectivity that Benjamin loved to hate to the conceptual photographs of August Sander, used as a structuring device organizing multiple rooms. To follow a thread, Sanders’s portraits are types not characters, nodal points in a rational and alienating discourse. Out of reified modernity, aesthetic postmodernity results—the totality as Cindy Sherman. Perhaps the show is inspired by Babylon Berlin, or maybe French l’art pour l’art coming to terms with German social construction. While there was much that was already seen, perhaps not the same way in Paris. Montmartre and the bookstores of Les Abbesses drew us on, where the new edition of Perec’s Lieux (Inédit) could be found. The Bateau Lavoir was where we left it the last time, as crowds of revelers hinted it was time to go home and pack. Past the monument to repression that is the Basilica Sacre-Coeur, we headed for the métro at Chateau Rouge. Françoise told us some of her friends refuse to use that station, but “I like Chateau Rouge” is my Paris T-shirt.

Monday, June 27

Thalys Paris Nord > Köln HBF

the niu Mill, Genovevastraße 26

Daniel Schulz

[not Christian Lux]

[not Ekaterina Drobyasko]

[not Claudia Franken]

[not Karl Thönissen]

The Kathy Acker Reading Room

@ Universität Köln

Photographische Konzepte und Kostbarkeiten

@ Die Photographische Sammlung

Into the Expanse: Aspects of Jewish Life in Germany

@ Kolumba Museum

The high-speed train floated past Aachen, where Claudia Franken and Karl Thönnissen were packing up and leaving Germany for good, expatriating to Cádiz. There was a chance to get out and tour the Roman baths at least, but as American barbarians of the frontier we needed to meet our destiny on a pre-planned route. Luckily no such meeting took place, as we would find out later. Aachen (Aix-la-Chapelle) is the 28th largest city in Germany, whose culinary speciality is Aachener Printen, a type of gingerbread. Eugene Jolas arrived with American troops after liberation on 21 October 1944 and immediately began a project of reeducating German newspaper publishing along the lines of objective reporting standards, totally reversing his avant-garde project of polylingual babblespeak in transition (a research topic). Our destination was Köln, Cologne, once Colonna, named for the Roman garrison that occupied it at the border of the empire, and root of the words colony and colonial, another research topic. “These colonial cities grew out of loathing / Into something forgetful, although angry with history,” John Ashbery might have written. The cathedral stands, though we deliberately chose a hotel far from it its colonial domination of the city, in an area of postwar concrete and Döner stands. Carla’s plan was to visit the Kathy Acker Library at the university to examine Acker’s collection of Beat poetry, a research topic. Daniel Schulz, director of the library and a grad student working on Acker and San Francisco in the 70s, showed her around. We are part of his research topic, perhaps, so we brought him a set of The Grand Piano. While Carla and Daniel checked out the well-thumbed trade paperbacks and smaller editions Acker had collected or absorbed, I made my way to Köln’s Media City, a planned area of office buildings bordering on August Sander Park, where I walked along the rail lines. On view at the Photographische Sammlung was a meticulously curated exhibition of German conceptual photography beginning with Sander, a Köln native, whose work we had seen in massive amounts in Paris but there is more. I picked up an equally massive catalogue of German bunker photos by Boris Becker, another entry into Pig Heaven. From there I walked to the Kolumba Museum, a conceptual project of the Catholic Archdiocese that displays objects of antiquity, back to Roman times, along with modern and contemporary art. There is no wall copy but the visitor is given a printed book with copious glosses on each work, an archive in itself. From there it was a walk around the corner to a taproom where a custom of endlessly refilling glasses of pale blond beer is observed. Kölsch is a style of beer originating in Cologne. It has an original gravity between 11 and 14 degrees Plato. In appearance, it is bright and clear with a straw-yellow hue. I drank many waiting for Carla and Daniel to arrive from their archive tour, then we dined on sausages, potatoes, and fried fish. We were in Germany for real. But all this is fol-de-rol, delaying the inevitable. Returning to the hotel for a legal Zoom meeting, something bad was about to happen. I was unable to meet Christian Lux for an interview due to COVID, while Katya Drobyasko had gone camping with her son.

Tuesday, June 28

ICE Köln Messe/Deutz > Frankfurt

ICE Frankfurt > Kassel Wilhelmshöhe

Hotel MountainPark, Im Druseltal 93

[COVID day 1, CH]

Documenta is history, of its own and of my experience of it, that is uniquely valuable. I first came to the 100-day, city-wide exhibition in 2002 for the 11th installment, the outset of its series of global projects. Documenta is a work of art in itself that builds a horizon of the global using the historical nonsite of Kassel, a former industrial city involved in German munitions manufacturing that was heavily damaged in the war. The 2002 exhibition, organized by the Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor, opened in the main hall with a direct reference to experiences of displacement and exile: an installation by Iranian sculptor Chohreh Feyzdjou, whose ironic “boutique product” was a warehouse of oily textiles and packing crates, distressed material baggage lost between an original moment of culture and its fate in art. Documenta was a window on the global art of its time from a perspective not in thrall to New York’s metrocentric account of modernism, which appears more globally provincial by the minute. Just today, I read the Times’ half-baked review of the Bernd and Hilla Becher, which describes their serial photography of disused industrial buildings as “curios” by “delightful obsessives” that elicit “the calming effects of Sol Lewitt or Agnes Martin.” The Bechers’ documentation of the material remains of industrialization is completely subsumed in capitalist exchange that goes by the name of “abstraction,” with no hint of negativity or social logic; I am still still fuming (see my chapter on “Negativity,” which contrasts the Bechers with Neo Rauch). I am trying to get to, while avoiding coming out and saying directly, what seemed so misguided about Documenta 15, which made a grandiloquent attempt to provincialize the metropol, as a continuation of its global project, in appointing the Indonesian curatorial collective ruangrupa to organize the show under the concept of lumbung, or “collective reciprocity.” From its website: “ruangrupa is the Artistic Direction of the fifteenth edition of documenta. The Jakarta-based artists’ collective has built the foundation of their documenta fifteen on the core values and ideas of lumbung (Indonesian term for a communal rice barn). lumbung as an artistic and economic model is rooted in principles such as collectivity, communal resource sharing, and equal allocation, and is embodied in all parts of the collaboration and the exhibition.” What rhetorically failed was the real-time articulation of the show’s concept—the connection between the work of art and the material histories and artistic intentions and curatorial insight it may convey. Many prior examples of global art at Documenta accomplished this: Choreh Feyzdjou’s installation in documenta 11, or Ai Wei-wei’s oversized collapsing screens in Documenta 12; or Kadar Attia’s WWI ethnographic installation of reconstructive surgery and “native” sculpture; or Etel Adnan’s lucid landscapes painted from exile, both in dOCUMENTA 13. In its place was a nominated or ordinated top-down vision of “the global” which was then delegated, in a daisy chain of bureaucracy, to a subordinate group of curatorial teams. A kind of NGO rhetoric of representing the global (“they cannot represent themselves, they must be represented,” as Marx wrote in The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte) to metropolitan audiences resulted, with didactic intentions largely underdeveloped beyond displays of information or material. I refer the reader to the catalogue or website or reviews for proof. Yes, there were a few good and surprising works here and there: one was Britto Art Trust, from Dhaka, Bangladesh, which manufactured “a small-town bazaar stocked with food items in crochet, ceramic, metal, or embroidery . . . to understand how foodstuffs are divorced from their natural origins.” But what really worked here was the refabrication, on an eery, larger-than-life scale, of everyday market goods in nonfood materials, a reversal of any “return to nature.” Or in the Wajukuu Art Project’s installation of “Maasai traditional housing and the informal aesthetics of slums [where] visitors enter the tunnel, wander into a darker, coded space to experience multimedia expressions of Wajukuu-affiliated artists”—a staged reenactment of cultural displacement that imports Nairobi slums to Kassel. There was also a whole building devoted to the Indonesian collective Taring Padu, whose agit-prop mural was taken down after charges of anti-Semitism, in a major controversy of the exhibition. Other didactic projects are Hamja Ashsan’s Kaliphate Fried Chicken signage, encountered at multiple sites; a number of voluntarist art projects encouraging hands-on creativity as forms of sustainability, evoking back-to-the land agrarian communities with thatched roofs; “The Question of Funding,” which invites global stakeholders “to share perspectives around funding and the ethics of survival”; and the Documenta catalogue itself, a manual of how to interpret the exhibition that supplied overarching narrative coherence for the viewer’s experience of displacement and disconnection. I was passionately dismayed and fatigued, trekking from building to building looking for what I had been so excited to find in the past. It was hot, and Carla decided to stay at the hotel to get some rest. “We’ve been doing too much; I don’t think I can keep up with you; I’m just not up to this.” Unknown to either of us, this was Day 1 of Carla’s case of COVID. We went to Documenta to catch up with the global, but in an irony of fate it was there that the global pandemic caught up with us.

Wednesday, June 29

Documenta 15

[COVID day 2, CH]

ICE Kassel Wilhelmshöhe > Berlin Ostbahnhof

Ebertystraße 54, Friedrichshain

Ragna Berg

Carla took her time getting ready to go out, for what would be a brief trip to Documenta before the train to Berlin. I was feeling a bit exhausted and spacey as well, to judge by the following anecdote. Coming up from breakfast, I pressed the elevator button for 2, coffee and notebook in hand. But I had left my phone in the restaurant so I put both down on a ledge outside our door and went to retrieve it. Returning to the erstes Geschoß, coffee and notebook had magically disappeared from the ledge where I had put them. Cleaners were around—perhaps they were overly scrupulous in tidying up; perhaps I had broken a rule about leaving personal objects in the hall. I went to the look for the cleaners, then the staff. I must have my notebook or the evidence of our trip will be gone; I started to feel anguish of the lost object type. With professional calm, the staff initiated a search of multiple CC TV monitors, but neither notebook nor coffee could be seen. In the security room, we poured over videos of the hotel from all angles over the past twenty minutes. No notebook was visible at any time on the erstes Geschoß. Finally one of the staff figured it out, went up to the zweites Geschoß, and bingo. Here’s your precious notebook, Herr Watten; your coffee is still warm. Americans often mistake their “second floor” for the German erstes Geschoß—or was this the onset of COVID? I later hoped that I had maintained social distance through the episode. After copious apologies graciously deflected—it happens all the time—we finally made our way to Kassel, hoping at least for a clean exit to Berlin. I was done with rhetoric of preplanned payoffs of most of what I had seen at Documenta, so I lent Carla my ticket and visited the exhibition bookstore, where I picked up an invaluable catalogue of the earlier history of Documenta, from its origins in postwar recovery and denial, framed by antagonisms of the Cold War. At the Documenta Archiv, I am buzzed in and ask to speak to a curator, wanting to make sure they have my essay on “The Global Archive.” I sense some defensiveness about the current show and thus the larger mission of Documenta, now under political scrutiny at the highest levels. In such manner the political attacks the autonomy of art, even its global incarnation, and art needs to anticipate that pressure. Meanwhile wir Negativen retrieve our luggage at the train station and get set for the entry into Berlin. Arriving at Ostbahnhof, with its DDR modern design, we find our way to a remodeled Mietkaserne in Friedrichshain, near the oversized Olympic swimming pool at Landsbergerallee, with Vietnamese take-out and wine bars on every corner, looking forward to our return after three years away.

Thursday, June 30

Covidzentrum Eastside Mall, Kreuzberg

Petersburger Apotheke, Friedrichshain

[COVID day 3, CH; day 1, BW]

Now comes the onset of COVID. Carla wakes up, says I am feeling tired and crummy, takes a test. It’s positive. The COVID moment is a type of event—once the event has begun, there is nothing outside it. The COVID duration—the multiyear dread that precedes the event—on the other hand, is the anxiety that precedes the event, of what has not been experienced. Mortality is the former, vitality the latter. Mortality is irreducible fate, not a matter of choosing. Living is destiny—it is the condition in which each half-formed particular contributes to the unfolding whole. The transition from duration to event is terrifying, but is barely experienced directly. It happens all the time. Suddenly one’s awareness of bodily continuum is diminished, and it could be diminished further—it can happen like that. But people get over it; we will get over it in time. Now we are making phone calls and looking online for what to do next. Berlin has innumerable testing sites; we choose one near the Warschauerstraße U-Bahn, late-night rendezvous for party goers with their Wegbier on the way home, one more time. Now under construction are new office buildings and the East Side Mall, which looms like a gigantic boombox over the Spree. The Covidzentrum is in a side entrance posted with a sign; we register on our phones; take the test. The testing-angel is a comedian off duty; he performs his ritual incantation: you’re negative; you’re positive. What to do next. We go home, make phone calls, look online. Asa advises Paxlovid; Donna says go to the nearest Apotheke to see how you get it; Ragna advises the Bundeswehr Krankenhaus, hospital of the German military, as the best clinic; do not go to Friedrichshain Klinikum, she says. At Petersburger Apotheke I am told they can order Paxlovid but I need a prescription. How do I obtain one? Here is a list of doctors in the neighborhood. I go to two, both closed. On the last day of the month, June 30, German doctors close early to fill out tax forms. I telephone clinics that are still open, looking for someone who can prescribe (also considering monoclonal antibodies as an option). The Bundeswehr hospital has a 24/7 line; I can get a prescription but it will have to be tomorrow; I ask Petersburger Apotheke to order one dose of Paxlovid for Carla; they agree. I go home, order take-out Vietnamese noodle soup, continue to look for resources online, inform recent contacts. I am only hoping we were not contagious when we visited Linda in the hospital, and our other friends as well.

Friday, July 1

Covidzentrum Eastside Mall

Bundeswerhkrankenhaus, Mitte

Dr. Behruz Foroutan > Paxlovid

Petersburger Apotheke

[COVID day 4 CH; day 2, BW]

I wake up after a night of fever dreams, test positive. This time we are both. Dr. Foroutan is our prescription-angel; he returns my call at 7 AM after the night shift; I can prescribe for you but I need positive test results; you must get them and be at the clinic by noon. Back at East Side Mall by the M10 tram, mask firmly in place, I get my result. At the Bundeswehr hospital, an invitingly clean space, Dr. Foroutan goes over our histories; prescribes. Then by cab to the Petersburger Apotheke, where Carla’s dose has arrived; the second will come that afternoon. We have now been on public transportation and cabs all over Berlin during the onset of symptoms—there was no other choice. Ragna has graciously agreed to extend our stay in Friedrichshain; I rebook our flight; we wait for Paxlovid to kick in.

Saturday, July 2–Sunday July 3

[COVID days 4–5 CH; days 3–4 BW]

Whose Universal? There is a Fundamental

Paradox at the Heart of Modernity: A Conference

on Humanist Ideals and Colonial Reality

Berlin Biennale, 2–3 July, online

[not Shane Anderson book launch

for After the Oracle @ Hopscotch Reading Room]

The symptoms are what are called “mild”—fever for a few days, tiredness, body aches. But which way this disease will go is anyone’s guess. Regardless, an event has taken over and will continue its course. After the second day of Paxlovid, fevers are gone but we are tired, sleeping, spaced, out of it. The Friedrichshain apartment is a nice place to experience this event, which becomes mapped onto the space itself. The ceilings are high; there is a long hallway separating rooms; wood floors and pleasant furnishings; IKEA kitchen with amenities, including an up-to-date coffee maker. The wrought-iron balcony overlooking a playground, the Höfe or courtyards typical of 5-story Berlin buildings, trees, with more recent construction in the background, becomes a window on our well-being to come. This weekend there is a certain amount of partying going on, nonstop techno in the bass register. I feel very much at home in Berlin as we wait for things not to happen, to happen less. Sunday there is a streaming event of the Berlin Biennale, laying out its decolonial agenda, so we tune in online. The program is ambitiously overstated, but each speaker has had hands-on experiences within it: Rasha Salti describes democratic struggles after the Arab Spring; Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz narrates the democracy struggle in Bolivia and its serial coups; Katrine Dirckinck-Holmfeld relates decolonial protests in Denmark, exposing its slave trade through the symbolic action of pitching the statue of a founding father/slave trader into the harbor. In each case, the narrative comes with risks and elicits solidarity, even at this remove. Later that afternoon I feel well enough to venture out to a bench in the playground below, masked on and distancing. Our tendency in each instance is upward, to the good, toward well-being.

Monday, July 4–Wednesday July 6

Covidzentrum Eastside Mall

[COVID days 6–8 CH; days 5–6 BW]

Rethinking Lyric Communities, with Jonathan Culler,

Daniel Tiffany, and Francesco Giusti

Reading with Vahni Anthony Capildeo, Christian Hawkey,

and Daniel Tiffany @ ICI Berlin (virtual)

12th Berlin Biennale @ Hamburger Bahnhof

Time is the work of repair. In the city of former ruins, we sequester in place. Apart from taking the M10 everyday to Warschauerstraße, we are ordering groceries and food online and refraining from going out. Monday’s livestream event, an Oxford University-in-Berlin conference on “Lyric Communities,” is a perfect release for poets in COVID jail. The question of lyric’s relation to community is one I could answer in my sleep, resting my head on a pillow of Rancière. But let’s see how they do: first off is Jonathan Culler—nice to see you in Berlin, been a while. He recalls that the lyric, for instance Baudelaire, invokes a “you,” hypocrite lecteur, and thus a form of community. Also there are communities of lyric practice. Then, finally, lyric has a relation to song in a community, for instance at a baseball game at Fenway Park, where one can join in and sing “Sweet Caroline”—or maybe “We will we will stomp you” at another venue. Then Jonathan Culler breaks into song—a karaoke moment—inviting us to join in: “Hands, touching hands / Reaching out, touching me, touching you.” This is an absurd payoff moment for lyric theory; I can’t believe Culler is serious. Later, in the Q&A, he opines that there are dark aspects of community in this invocation—help me, William Carlos Williams and your “Crowd at the Ballgame”—and from my COVID bunker I jump in and give a mini lecture on the turn to language and community, from outer darkness as it were. I remember the launch of The Lyric Theory Reader as a call to order, with fanfare, about the same time A Guide to Poetics Journal was published, only to be ignored. I must be getting better, I care about something. Daniel Tiffany, whom I have met several times in Berlin, follows with a lecture on logophobia, the hatred of language as an aesthetic practice, which he will perform in a reading later on. As the author of “Plan B,” ventriloquizing the public discourse of 2016 as a form of negative community, I am down with that. I do not recall the point of Francesco Giusti’s talk, “Gestural Communities: Lyric and the Suspension of Action,” except that lyric has now become a placeholder for what counts as literariness, pace Shklovsky. Later that night Tiffany read a longish poem demonstrating self-hating speech in action, a kind of cento of appropriation and misapprehension, a continuation of the language critique of the lyric without doubt. Christian Hawkey follows to read a long example of/essay on translation where alternate glosses and misreadings combine to destabilize the transmission of the lyric, and I am also down with that. German lyric immanence be damned! I must be feeling better. Finally, Vahni Anthony Capildeo presented the most affected display of nouveau literary orthodoxy I have seen, with the Times Literary Supplement hovering in the wings. Performing new styles of literariness to meet new community standards; rewriting the Odyssey as lyric fragments! I need to go out. On Monday, we will tentatively walk in Volkspark Friedrichshain, a 19th-century park of the working class rededicated by the DDR after World War II as site of memory and playground, with monuments to the Polish resistance, outdoor cafés, gardens, fountains, and two mountains of rubble that effectively create the romantic illusion of a barrier between park and city beyond. On Tuesday I roamed a bit farther, hiking up one of the Trümmerberg and visiting the cemetery to the martyrs of 1848. Finally on Wednesday, Day 5 after onset for me, and I hazarded a first look at the Berlin Biennale.

Thursday, July 7

Covidzentrum Eastside Mall

[COVID day 9 CH; day 7 BW]

12th Berlin Biennale @ KW Mitte

Reclaiming Space: Birgit Brenner, Stef Heidhues,

ChristineHill, Maix Maxer, Lada Nakonechna

@ Galerie Eigen + Art

Pro QM Buchhandlung, Prenzlauerberg

Leon Kahane, gedenken unserer durch die Tat!

@ Nagel Draxler

Lauren Coullard, Covered in Feathers @ Mountains

Fortunately, this was the day I tested negative, and Carla was now asymptomatic, so we could cautiously head out. The Berlin Biennale was the answer to the disappointments of our Kunstreise to the Continent, in its postmodern incarnation. This was the 12th installment; I had been coming since Berlin Biennale 4, “Of Mice and Men” (2006). which distributed art up and down Auguststraße, the breakthrough art zone, with compelling effect. A number of the works had an aura of discovery—things never before seen, for instance Robert Kusmirowski’s Wagon, a full-size replica in styrofoam and cardboard of a concentration camp train; or Marcel van Eeden’s comic-book narrative of a made-up artist/double agent who he convincingly ventriloquizes as K.M Wiegand; or Oliver Croy and Oliver Elser’s scale models of The 387 houses of Peter Fritz, insurance clerk from Vienna—though I see now the vast majority of artists were men. The 12th Biennale was themed as anticolonial and non-Eurocentric, curated by Kadar Attia, and was an estimable success. Where Documenta 15 tried too hard to organize everything within a rhetorical collective umbrella, Berlin Biennale 12 allowed for critical distance, relative values, site-specificity, and informed curating. Where previous biennales had gone out of their way to be all over Berlin—becoming a Kunstreise in itself—this one made use of four well-known venues plus one nonart site, the Stasi Archiv in Lichtenberg. The point is to create a critical distance in the service of decolonization, an inevitable hybrid of Kant and globalization but that brings out mutual values on both sides. Where German cosmopolitanism may be the last refuge of scoundrels, given how the lore of Dichter und Denker led inexorably to National Socialism, as Adorno has pointed out, it may also be a site of reparation since that historical fact. Reparation is not only theme but goal of Biennale, which it tries to achieve in multiple senses. There are many routes to reparation; the first is the enumeration of crimes and the assessment of the damage. This has been going on, in however obstructed form, since the Nuremberg and Frankfurt trials; it is the basis for the efflorescence of historicism in German aesthetics since the rebirth of modernism after the war. Rather than go through high points of the particular occasion, I simply recommend it as worth the trip to Berlin—hence a partial justification for all that impeded or befell us. In terms of missed encounters, it was also gratifying to find Simone Fattal’s In Our Lands of Drought the Rain Forever Is Made of Bullets (2006), whose inscription from Etel Adnan’s poem “Jebu” is presented in her memory and for the Palestinian diaspora. What stood out in the work of the Biennale was its invitation to read, but also its complex occasions. A remarkable example of reading, in fact, was Hasan Özgür Top’s “The Fall of a Hero,” an investigation of ISIS propaganda through its privileged typeface, Trajan—from Trajan’s Column in Rome but also widely used in Hollywood epics. The video installation in an interrogation room at the Stasi Archiv was, as both surrealists and Adorno might agree, marvelous. There were many further examples of works that could be pondered over or reflected on, but the primary result was to ask for more, to see more and reflect on what one sees. From the KW (Kunstwerk) venue that begins the exhibit, we found our way to Eigen + Art, the historical gallery that brought the Leipzig School to awareness in the 80s and later. On view was a group show that included a meticulous assemblage by Christine Hill, using writing supplies as a visual metaphor, and the negative découpages, made by peeling off emulsion from photographs, of Lada Nakonechna, a Ukrainian artist, which led to an informative discussion with the gallerist on new Ukrainian art. At the Hamburger Bahnhof, which I had been to the day previous, there was also a strong presence of Ukrainian art—a digital reconstruction of the site of Babyn Yar in Kiev, making its recent attack by Russian missiles even more a symbolic outrage. Also at the Bahnhof, Clément Cogitore’s video of Krump dancers, to the music of Couperin’s Les Indes galantes, was a standout decolonial work, while Jean-Jacques Lebel’s installation of Abu Ghraib horror shots was excessive. But opposed to the generalized North-South frame of Documenta 15, the specific reference to U.S. aggression in Iraq, or Russian aggression in Ukraine, was necessary. Ramping up my agenda in Berlin, I had to keep going, so Carla went back to the apartment while I visited the urban theory bookstore ProQM and galleries in Rosa Luxemburg Platz.

Friday, July 8

Covidzentrum Eastside Mall

[COVID day 10 CH; day 8 BW]

12th Berlin Biennale @ Stasi Archive, Akademie der Künste

Pariser Platz and Hansaviertel

Tl;dr—perhaps a risk. But in a world of particulars, it does not serve to generalize. “What did I see? Particulars!,” wrote Allen Ginsberg in Indian Journals without naming them individually. But he paused to notice everything. Without meaning to, I have recalled my early interest in global writing via Ginsberg’s journals, which I will never cease to admire. They, too, ply the boundary between reflexive cognition and the body in all its vulnerabilities—in his case, drugs taken for insight into his embodied condition but also fevers and dysentery that risked morbidity. The reflexive awareness of the body during an episode of COVID, we would find, is limited. It is rather a kind of lessening of acuteness or subtraction from being, and very difficult to accurately assess (as is the risk of infection when seen as a matter of numbers, graphs, maps, or protocols). For this reason the daily testing took on increased meaning as we headed back to East Side Mall one more time—Carla did not get a pass, though symptoms were in abeyance and guidelines, at least some of them, said one could stop isolating on day 10 in their absence. Continuing, then, with our tour of the Biennale, we visited the Stasi Archiv and then took the newly completed U5 to the city center. Each of these venues was chosen as a site for one aspect of decolonial or anti-Eurocentric critique; the Akademie der Künste, right next to Brandenburg Gate, had the burden of postcolonial negativity. As a result the work was often didactic, and foregrounded that intention in its own right. At the original Akademie der Künste in the Hansaviertel, on the other hand, the spacious 60s-era modernism became the site for large-format ecocritical installations, all of which were experiments in representation as much as conclusive results. Somewhat exhausting to view, much less recount, but there was an element of satisfaction in the thoroughness of the curatorial mission. How the point gets made is the point, even if it takes work to get it; it must be a form of voluntary engagement, an act of participation; not an easy trick to pull off. Returning East, we stopped by ancient haunts in Prenzlauerberg to find Bar Gagarin, which had offered ice-cold vodka with its Worker, Peasant, and Intelligentsia plates, is no longer in business—Ostalgie is done—but Restaurant Pasternak next door still has “traditional values,” so we went there.

Saturday, July 9

[COVID day 11 CH; day 9 BW]

12th Berlin Biennale @ Hamburger Bahnhof

Hopscotch Reading Room

[not Siddhartha Lokanandi]

Oliver Osborne, German Afternoons @ Tanya Leighton

Entangled, group show @ Dorothée Nilsson

Joan Jonas, past thought revised @ Heidi

Fedir Tetyanich, Everywhere Is My Endless Body

@ CCA Berlin

Lena Henka, Auf dem Asphalt botanisieren gehen

@ Klosterfelde

Günther Förg, Exposition Collective 1974–2007

@ Max Hetzler

Ian Davis, The Mass Ornament @ Galerie Judin

[not Galeria Plan B]

[not Barbara Wien]

Rave the Planet Parade, Kurfürstendam

The aim of my Kunstreise in Berlin was a return to Park am Gleisdreieck, “a public green and recreational area in Berlin . . . located on the wasteland of the former Anhalter and Potsdamer freight stations at Gleisdreieck. The park, realized in part with citizen participation, is characterized by wide lawns with sunbathing areas and historical relics from the site’s railroad days. Areas called ‘track wildernesses,’ described as ‘unsecured,’ dense, wild growth areas that had developed out of the old tracks, signal remnants, track pits, and water ponds, form a biotope of their own,” surrounded by an urban district of over 30,000 immediate residents. “I have seen the future and it is now,” wrote Dreiser on visiting the Soviet Union in the 20s (not to mention the rise of Stalin). I feel the same way about Park am Gleisdreieck: it is a zone of futurity, where construction, mobility, ruin, wildness, civility, and playfulness mix. Each of these elements has a specific correlate in the Park, which, as whole, is much like a Lissitsky Proun, an imagined space where quasi-functional elements create a rhetoric of pure possibility, a three-dimensional Gesamtkunstwerk. The elevated U2 station Gleisdreieck is the nominal entry into the park, which opens immediately onto a space of still-operational U-bahn lines, de-purposed rail beds, open spaces, and concrete paths. All routes through the park are a form of traversal; the rectangular grid is displaced by a series of triangles of uneven lengths—the Dreieck as a principle of construction. I chose one angle of traversal, from the Brlo beer garden to the Fürstenstraße exit, on my way to Siddhartha Lokanandi’s Hopscotch Reading Room, which looked to be reveling in its own orderly disorder—a principle of literary construction yet to come. From there, a series of entry-level galleries led to the urban shock of another demonstration of tens (or hundreds) of thousands of people and thundering loudness, the renascent Love Parade now titled “Rave for the Planet.” How to use the verb hailed (past tense or present participle) in a sentence: “Kant was hailed by some as a second Messiah”—the first example to pop up in an internet search. After Althusser I say, “Rave for the Planet” hailed me on this occasion. Ducking in and out of various galleries on Potsdamerstraße, I felt alternately taken up, rolled over, passed by, and cast aside by the surging crowds, all moving in one direction. In the era of globality, this must be the new meaning of hailed, “to be caught in an irreversible process of relentless momentum.” Crossing over the surging crowd merely to get to the other side of the street was an adventure and a test of will; there was Kunst over there and I must see it. In one instance, it was the recovered work of a Ukrainian outsider artist whose work was being preserved from the perils of war, I was happy to know about it. In another, it was a career retrospective of a gallery artist who wraps his work in the colors of the German flag, of little interest. Deviating from the flow of the event, I tracked back to the Park in the hope of a stolen moment with an IPA. Party-goers by the hundreds confronted me at the entrance of the Park, pulsing in the opposite direction. Back at the Brlo, I had had my glimpse of Berlin wildness and paused to reflect, anticipating this writing as its completion.

Sunday, July 10

[COVID day 12 CH; day 10 BW]

Eugene Ostashevsky

Donna Stonecipher

[not Florian Werner]

[not Uljana Wolf]

The hope was that on our last day in Berlin, the true object of our voyages—getting in sync with friends after three years of COVID expectation, ten days of COVID recovery—could be realized. The prospect dawned brightly with an early morning walk with Eugene Ostashevsky, from Tiergarten along the banks of the Spree, with its futuristic office buildings and new apartments. We talked translation, of course, and mulled over what could count as “cultural translation,” after Ostashevsky’s recent lecture at Berkeley, where he advanced a theory of linguistic translation that would take into account the always partial, incomplete knowledge of more than one or several languages, and the translator’s position among them. It is a global not a postmodern theory, not troubled by the “relativism” that has defined translation studies since the 90s. A refunctioned concept of the “dominant” and the overdetermination of poetic language, straight out of Jakobson, could take its place—with translation becoming a made space between languages. Then how to bring cultural translation into the mix—what I tried to accomplish in my translation of Etel Adnan. The conversation would have gone much further, and I wanted to hear something about the impact of the war in Ukraine on expats in Berlin, but I needed to get back. Carla was feeling exhausted and unsure, worried about travel the next day, so I decided to cancel our lunch date with Florian Werner and later coffee with Uljana Wolf and simply hang out, take stock of the situation, and prepare for our global return. Dinner with Donna was still possible, so we managed to do that, finding a table outside as the temperature cooled and a wind came up, reconnecting at a most companionable level. And then—we will make the big leap, get back to base, quit our sequestration in Berlin. The cab would come at 5 AM and we would embark at the new BER airport, a cold monument to national destiny.

Monday, July 11

KLM BER > AMS

Delta AMS > DTW

[COVID day 13 CH; day 11 BW]

The return trip was not the least of our global worries. The pressure of pent-up desire to be anywhere but where one has been over the past three years; the staff shortages at airlines and resulting domino effect of canceled flights and long lines; and the need to screen passengers for both health and migration concerns raised the bar of anxiety to new levels. Getting on the short hop to the KLM/Delta hub in Amsterdam meant adhering to Dutch rules for entry, which ask for a negative test after 10 days; American regulations, in a h/t to the airline industry, require no proof of vaccination or a negative test result for citizens on entry—but it does require them of resident aliens, in a moment of sheer unreason. Either there is an infection being carried or there is not, but the decisions are based on numbers, projections, the bottom line, what counts as a “citizen,” and how they will vote—politics, in other words. I believed myself to be over the infection, but as I would find out I was not. Carla, on the other hand, was without symptoms on the twelfth day but had not received a negative test. It did not matter in the slightest; we were not asked anything to get on the plane, so we masked up and waited. The flight was full of unmasked passengers, many coughing and sniffling, all returning to the U.S. after being exposed to crowds in Europe, and was sheer torture. Once back, I felt exhausted and slightly feverish, with a headache that I attributed to the airplane air, and thought we ought to get tested before going home. We did: I was positive, an example of post-Paxlovid rebound that is now in the news; Carla was negative. I could look forward to another week of feeling bad, but likely was not all that contagious. Thus my account of our three weeks traveling in Europe, in the third year of a global pandemic, to see friends and art. I was entertained, as I rested and recovered, by Shane Anderson’s Berlin expat memoir, the best of that genre to date.

Notes

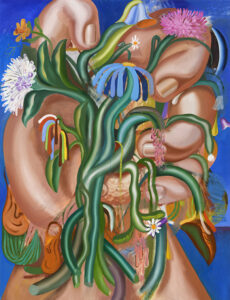

Image: Kristina Schuldt, Unverwüstlich, 2022. Galerie Eigen + Art, Goslar.

Books:

Shane Anderson, Letter to the Oracle; or, How the Golden State Warriors’

Four Core Values Can Change Your Life Like They Changed Mine (Vellum)

Sean Bonney, Letters Against the Firmament (Enitharmon)

Carla Harryman, Cloud Contata (Pamenar Press Poetry)

Anthony Joseph, Sonnets for Albert (Bloomsbury )

Rachel Levitsky, Against Travel / Anti-Voyage (Pamenar Press)

Carlos Soto-Roman, Nature of Objects (Pamenar Press)

Keston Sutherland, Scherzos Benjyosos (last books)

Cosey Fanni Tutti, art sex music (Faber & Faber)Jean-Marie Gleize, Jusqu’à ce que l’écran se vide (zoème)

Emmanuel Hocquard, Une Grammaire de Tanger (P.O.L.)

Victor Hugo, Les Orientales/Les Feuilles d’automne (NRF)

Georges Perec, Lieux (Inédit) (Seuil)

Benjamin Peret, Contes/Histoire naturelle (Les Perséides)Access to Secrecy: Exhibition on the Stasi Records Archive,

Stasi Unterlagen Archiv

Boris Becker, Bunker, Die photographische Sammlung

Cornelia Parker, Tate Britain

Documenta 15 Handbook, Documenta

documenta: Politics and Art, German Historical Museum

Into the Expanse: Aspects of Jewish Life in Germany, Museum Kolumba

“Looking in a distorting mirror”: The Case of Gilbert Radulovic

in the Stasi Records, Stasi Unterlagen Archiv

Separatists: Lada Nakonchena, Galerie Eigen + Art

Still Present!, Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art

Thinking through Ruins, ed. Enass Khansa, Konstantin Klein,

Barbara Winckler (Kadmos)