Pursuing the truth hidden in the archive, I could have called this entry “Poetry Wars,” as a hot-button topic. But that would be to give in to the facile and fetishistic, the already scripted. What I am interested in is learning from the traces of reception, what the reception of a work, an author, a movement gives us as information, in a kind of feedback loop, of the world in which it was meant to have its effect—to “win its way” as Stein wrote. But that course is never guaranteed. Whitman’s assertion of a reciprocity with the people, his readers—”I alone receive them with a perfect reception and love—and they shall receive me”—may be posited as an ideal that is impossible to achieve. And it is true that the reception history of Language writing often took place in an opposite sense—to the extent that populists could claim it had been rejected by the “people,” seen as a literary ideal. It could be said that the entire movement, as a group form of “negative capability,” held open its horizon of reception until some future time to come. Rather than empowering the reader, Language writing intuited its reception as something it could not yet wholly envision or grasp. The writing itself, I would now say, took form on the basis of an unknown futurity.

Pursuing the truth hidden in the archive, I could have called this entry “Poetry Wars,” as a hot-button topic. But that would be to give in to the facile and fetishistic, the already scripted. What I am interested in is learning from the traces of reception, what the reception of a work, an author, a movement gives us as information, in a kind of feedback loop, of the world in which it was meant to have its effect—to “win its way” as Stein wrote. But that course is never guaranteed. Whitman’s assertion of a reciprocity with the people, his readers—”I alone receive them with a perfect reception and love—and they shall receive me”—may be posited as an ideal that is impossible to achieve. And it is true that the reception history of Language writing often took place in an opposite sense—to the extent that populists could claim it had been rejected by the “people,” seen as a literary ideal. It could be said that the entire movement, as a group form of “negative capability,” held open its horizon of reception until some future time to come. Rather than empowering the reader, Language writing intuited its reception as something it could not yet wholly envision or grasp. The writing itself, I would now say, took form on the basis of an unknown futurity.

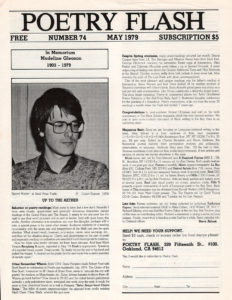

Returning to the files for evidence does not disclose a simple negative history; far from it. “The morning of starting out, so long ago” (Ashbery) was as legitimately optimistic as it could have been. In that sense, an “originary” moment, at least on the West Coast, might not be the December 1978 “canon-making” debate with Duncan over Zukofsky’s reception, but the May 1979 “focus on language-centered writing,” edited by Steve Abbott, in the Bay Area journal Poetry Flash. By that time, L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E had begun its four-year run of publication out of New York, and San Francisco small presses such as The Figures, Tuumba, and This Press had brought some of the early major works of the movement. But seeds of contestation or reaction were already evident. Alan Soldofsky’s “Language and Narcissism”—one of five contributions to the issue—was the first attested moment of “Language baiting,” and tended to overshadow the positive contributions of the forum. From that moment to Tom Clark’s cartoon parody of this author—likely drawn from the head shot on the cover of Poetry Flash—was but a little minute. And from that moment to the present, “forty years on” as Tony Green wrote, the discourse of populist antagonism to Language writing has been in place. Returning to the archive creates a series of talking points to comprehend what was at stake. … More