Pursuing the truth hidden in the archive, I could have called this entry “Poetry Wars,” as a hot-button topic. But that would be to give in to the facile and fetishistic, the already scripted. What I am interested in is learning from the traces of reception, what the reception of a work, an author, a movement gives us as information, in a kind of feedback loop, of the world in which it was meant to have its effect—to “win its way” as Stein wrote. But that course is never guaranteed. Whitman’s assertion of a reciprocity with the people, his readers—”I alone receive them with a perfect reception and love—and they shall receive me”—may be posited as an ideal that is impossible to achieve. And it is true that the reception history of Language writing often took place in an opposite sense—to the extent that populists could claim it had been rejected by the “people,” seen as a literary ideal. It could be said that the entire movement, as a group form of “negative capability,” held open its horizon of reception until some future time to come. Rather than empowering the reader, Language writing intuited its reception as something it could not yet wholly envision or grasp. The writing itself, I would now say, took form on the basis of an unknown futurity.

Pursuing the truth hidden in the archive, I could have called this entry “Poetry Wars,” as a hot-button topic. But that would be to give in to the facile and fetishistic, the already scripted. What I am interested in is learning from the traces of reception, what the reception of a work, an author, a movement gives us as information, in a kind of feedback loop, of the world in which it was meant to have its effect—to “win its way” as Stein wrote. But that course is never guaranteed. Whitman’s assertion of a reciprocity with the people, his readers—”I alone receive them with a perfect reception and love—and they shall receive me”—may be posited as an ideal that is impossible to achieve. And it is true that the reception history of Language writing often took place in an opposite sense—to the extent that populists could claim it had been rejected by the “people,” seen as a literary ideal. It could be said that the entire movement, as a group form of “negative capability,” held open its horizon of reception until some future time to come. Rather than empowering the reader, Language writing intuited its reception as something it could not yet wholly envision or grasp. The writing itself, I would now say, took form on the basis of an unknown futurity.

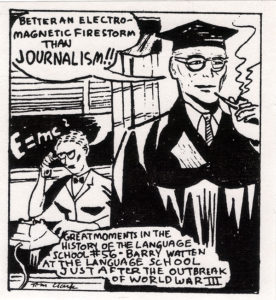

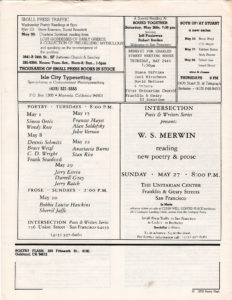

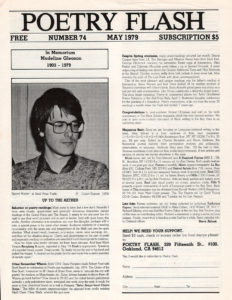

Returning to the files for evidence does not disclose a simple negative history; far from it. “The morning of starting out, so long ago” (Ashbery) was as legitimately optimistic as it could have been. In that sense, an “originary” moment, at least on the West Coast, might not be the December 1978 “canon-making” debate with Duncan over Zukofsky’s reception, but the May 1979 “focus on language-centered writing,” edited by Steve Abbott, in the Bay Area journal Poetry Flash. By that time, L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E had begun its four-year run of publication out of New York, and San Francisco small presses such as The Figures, Tuumba, and This Press had brought some of the early major works of the movement. But seeds of contestation or reaction were already evident. Alan Soldofsky’s “Language and Narcissism”—one of five contributions to the issue—was the first attested moment of “Language baiting,” and tended to overshadow the positive contributions of the forum. From that moment to Tom Clark’s cartoon parody of this author—likely drawn from the head shot on the cover of Poetry Flash—was but a little minute. And from that moment to the present, “forty years on” as Tony Green wrote, the discourse of populist antagonism to Language writing has been in place. Returning to the archive creates a series of talking points to comprehend what was at stake.

Poetry Flash 74 (1979)

[Note: clicking on the thumbnail opens it to a new page; clicking on the “magnifying glass” enlarges it to readable size.]

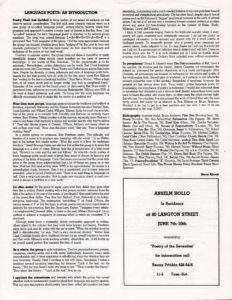

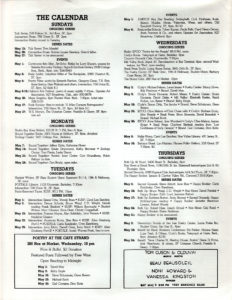

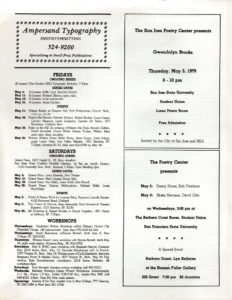

What characterizes the debate at this early moment is its openness; it is also important to site this discussion in the context of the maelstrom of activity at that present time. For this reason, I have uploaded all the pages of the issue of Poetry Flash, which adds to the earnest debate on language-centered writing the textual/visual evidence of readings, writer-in-residencies, and recent publications. Anselm Hollo, for instance, will be writer-in-residence at 80 Langton Street; Lyn Hejinian and Barbara Guest are reading at the Poetry Center, and Gwendolyn Brooks is at San Jose State; The Figures, This Press, and Tuumba have teamed up for an ad; and Intersection is featuring W.S. Merwin and Simon Ortiz, Frances Mayes, Frank Stanford, Stan Rice, Darrell Gray, and Bobbie Louise Hawkins, among others, in its weekly series. All that poetic activity, it may be said, contributes to being “language centered.”

After his editor’s notice of goings-on about town (including disruptions at the Grand Piano reading series, possibly the cat thrown at the audience during a performance of Frank O’Hara’s Try, Try), Steve Abbott’s magnanimous introduction sets the tone. Rae Armantrout’s “Why Don’t Women Do Language-Oriented Writing,” from L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E, puts the feminist/language question that will be answered by the publication of HOW(ever) a bit later on. David Highsmith pays tribute to the methods of language writing in his collage essay “Some Remarks on Recent Writing”; Geoffrey Young reads closely, and insightfully, into recent chapbooks published by Tuumba Press; and Alan Soldofsky raises the specter of narcissism, drawing on Christopher Lasch’s Culture of Narcissism, as a prequel to the symptomatic reading Fredric Jameson will make of Bob Perelman’s “China” just the next year. Two quotes, from Abbott and Soldofsky, work as bookmarks, even as these mini-essays should be reprinted, all together.

As a whole, the group is quite industrious. They’ve organized several presses, magazines, and reading series and a talk series. Individually, however, many seem uncomfortable and at times suspicious or self-effacing about the attention they are now receiving. Usually I find it exciting to talk with them. Sometimes I notice a tendency toward circuitous reasoning, for instance: “Look at the text, not the theory.” “But the text doesn’t make sense to me.” “Then consider this theory.” “Now about this theory . . .” And so on. (Steve Abbott, from “Language Poets: An Introduction”)

That it was evil for the Pentagon to refer to homes of the Vietnamese we bombed as “structures” and the invasion of Cambodia as an “incursion” was easy to acknowledge. But when words are dissociated from their denotations in the service of linguistic or literary theory the language poets find it all right in the service of technique. What is narcissistic in this approach is that underlying the theoretical consideration is a cool detachment that allows the poet to enjoy and flaunt his or her own intelligence. Readers who do not share the sensibility are dispensable. (Alan Soldofsky, “Language and Narcissism”)

Neither point is trivial: the circularity or reflexiveness of language and theory—albeit understood in an open form of making the work—versus the notion that the free play of the signifier gives rise to conditions of exclusion and mimic the deformed language of the public sphere. In the debate that follows, these two basic positions continue to generate a field of contestation, where gloves will be taken off quickly and more fundamental antagonisms laid bare.

Notes and links

Image: the cartoon by Tom Clark needs publication data.

Links: Archive 01: Zukofsky @ SFAI.