Like many who identified with the epochal chasm between The New American Poetry and mainstream verse of the 50s and 60s (whose benchmark anthology was Hall, Pack, and Simpson’s New Poets of England and America), I have been skeptical about Sylvia Plath; the cult of her suicide; the Plath, Sexton, Lowell, Berryman quadriviate; and any kind of confessionalism. As mainstays of workshop writing, these figures set in place terms for the personal lyric that is as close to a norm for verse culture as we have had—to the point that it becomes a cultural norm. But in the period since Plath’s mainstream and feminist reception in the 60s and 70s, much has changed. Lyric poetry has come under pressure from Language writing, and revisionist contextual and gendered readings have opened up Plath’s poetics, allowing one to see her negativity as critical and cultural, not simply formal and expressive.

In reading Jacqueline Rose’s The Haunting of Sylvia Plath, one finds the following description of her collage from 1960. The image places Plath into relation with the cultural logic of the 50s and clarifies her formal intervention at the same time. With that, and reading Plath against the negativity of Laura Riding—a substantial but little-known influence that Plath shared with Ted Hughes (who arguably saw themselves in terms of Graves and Riding’s mulitiauthorship and its eventual synthesis in The White Goddess)—one begins to construct a different Sylvia Plath. In the Plath/Hughes revision of the Graves/Riding couple, ascetic negativity in Riding meets Georgian versification of Graves to produce a hybrid lyric that distances and undermines the self in its expansiveness and contradiction. Rose sees this coupling as leading to states of fantasy in the work; it is anything but expressive of feminist anger or a confession of intimate secrets. Rather, a more public dimension of the presentation of self in Plath emerges, given support by the collage (as both content and form) in Rose’s description of it:

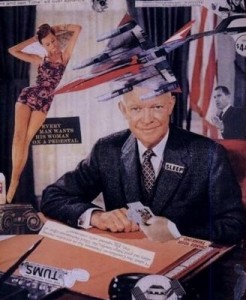

There is an extraordinary collage that Plath put together in the 1960s. At the centre, Eisenhower sits beaming at his desk. Into his hands, Plath has inserted a run of playing cards; on the desk lie digestive tables (‘Tums’) and camera on which a cutout of a model in a swimsuit is posed. Attached to this model is the slogan ‘Every Man Wants His Woman on a Pedestal’; a bomber is pointing at her abdomen; in the corner there is a small picture of Nixon making a speech. A couple sleeping with eye shields are accompanied by the caption: ‘It’s HIS AND HER time all over America’. In the top left-hand corner of the picture, this news item: ‘America’s most famous living preacher whose religious revival campaigns have reached tens of millions of people both in the U.S. and abroad.’ . . . Like all collages, this collage offers itself as a set of fragments. It is also not unlike a picture puzzle or rebus, which is the model Freud offered for the language of dreams. It shows Plath immersed in war, consumerism, photography, and religion at the very moment she was starting to write the Ariel poems. It shows her incorporating the multiple instances of the very culture against which these same poems, or one vision of these poems, is so often set. (Rose, Haunting of Sylvia Plath [Harvard UP, 1991], 9)

What remains is to fully bring Plath’s poetics into the framework of the same cultural logics that produced The New American Poets—think of Ginsberg’s A Supermarket in California, for instance—a revision that, come to think of it, gets us past the avant-garde/mainstream, or post-avant/School of Quietude, faultline that has troubled our thinking on poetry for so long.