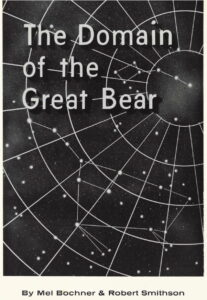

In a postscript to her major biocritical reassessment of Robert Smithson and his oeuvre (Inside the Spiral: The Passions of Robert Smithson), Suzaan Boettger recalls the arrival by mail of the just-published collection of The Writings of Robert Smithson (1979), edited by Nancy Holt and designed by Sol LeWitt. This watershed publication—at the boundary of literature and art, production and reception, content and design—truly launched Smithson into the “Domain of the Great Bear,” his art-historical destiny in the starry night. She sees it as a biographical convergence, writing in her copy:

In a postscript to her major biocritical reassessment of Robert Smithson and his oeuvre (Inside the Spiral: The Passions of Robert Smithson), Suzaan Boettger recalls the arrival by mail of the just-published collection of The Writings of Robert Smithson (1979), edited by Nancy Holt and designed by Sol LeWitt. This watershed publication—at the boundary of literature and art, production and reception, content and design—truly launched Smithson into the “Domain of the Great Bear,” his art-historical destiny in the starry night. She sees it as a biographical convergence, writing in her copy:

“This book arrived in the mail on my birthday, 1979, as I was on my way to deliver my first lecture—on earthworks.” While I had prepared by reading Smithson’s texts published in periodicals, the collection’s appearance on the day of my lecture seemed nothing less than serendipitous. (339)

Her lecture, given as a student in Peter Selz’s class on “Modern Sculpture” at Berkeley, would lead to her first article and, in 2002, a monograph on earthworks published by UC Press and then the present work—truly the task of a lifetime. It is the meteoric moment of impact of Smithson’s writings, along with their minimalist visual interpretation by LeWitt, that I want to focus on.

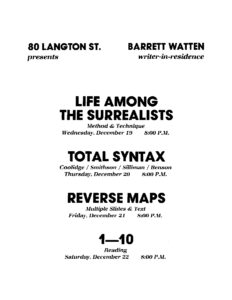

Little would she know that, that same year, a San Francisco avant-garde poet, not then affiliated with the university, would be inspired by the same volume. In December 1979, quickly following its publication but in the midst of exchanges with poet Clark Coolidge on Smithson’s writings, I lectured on “Total Syntax” during one of four nights as writer-in-residence at 80 Langton Street in San Francisco. Preceded by a talk titled “Life Among the Surrealists”—comparing avant-garde method in canonical surrealism with emerging Language writing—I began with a broad statement on the nature of “syntax” in art and writing—a statement whose breadth and risk of disciplinary transgression remains daunting today:

Little would she know that, that same year, a San Francisco avant-garde poet, not then affiliated with the university, would be inspired by the same volume. In December 1979, quickly following its publication but in the midst of exchanges with poet Clark Coolidge on Smithson’s writings, I lectured on “Total Syntax” during one of four nights as writer-in-residence at 80 Langton Street in San Francisco. Preceded by a talk titled “Life Among the Surrealists”—comparing avant-garde method in canonical surrealism with emerging Language writing—I began with a broad statement on the nature of “syntax” in art and writing—a statement whose breadth and risk of disciplinary transgression remains daunting today:

We can understand syntax as the relation of total sense to the order of elements in a language; that is, the way words make sense by means of their sequence in time. / However, interpretation demands context, and a statement also will be built of elements of its possible contexts. Syntax has a spatial dimension, if space is taken in the broadest sense to be not only physical but cultural and linguistic. / In art, one can speak of a syntax where the time element is not intrinsic to the work: one can speak of the syntax of sculpture. One can speak of the syntax of one word as a work of art or the syntax of a sequence of shots in a film. / Syntax taken in relation to art means: how is the statement of the work of art made, both in time and space. Works of art make a statement, though this statement is not to be written on a blackboard and diagrammed for all eternity. (Total Syntax, 65)

For a poet, this was a working definition that would lead, instanter, on broader implications: that the syntax of a work has both an inner (or intrinsic) and out (extrinsic) aspect.[1] This perception derived directly from Smithson’s writings on his work: not only the syntax of inner, formal organization but an outer relation to context, lifeworld, environment, history is entailed. The proof of this insight was Smithson’s demonstration of an “inner,” self-canceling syntax in his prose that would be congruent, but nonidentical, to the sculptural projects it envisaged and described. In the event of the residency at Langton, total syntax began with two talks on avant-garde art and poetry, continued with a performance fusing/separating language and image, and ended with a reading of a just completed volume of poetry—1–10 (1980), which could be seen as combining the serial forms of minimalism with surrealist and objectivist poetics.

For a poet, this was a working definition that would lead, instanter, on broader implications: that the syntax of a work has both an inner (or intrinsic) and out (extrinsic) aspect.[1] This perception derived directly from Smithson’s writings on his work: not only the syntax of inner, formal organization but an outer relation to context, lifeworld, environment, history is entailed. The proof of this insight was Smithson’s demonstration of an “inner,” self-canceling syntax in his prose that would be congruent, but nonidentical, to the sculptural projects it envisaged and described. In the event of the residency at Langton, total syntax began with two talks on avant-garde art and poetry, continued with a performance fusing/separating language and image, and ended with a reading of a just completed volume of poetry—1–10 (1980), which could be seen as combining the serial forms of minimalism with surrealist and objectivist poetics.

Suzaan Boettger’s biocritical exegesis of Smithson’s work in its entirety depends, as well, on such a syntax. On the one hand, there is a series of works (and restoration of a large body of early paintings that were ignored in his reception) and then there are the Rings of Saturn, as it were, of the history, biography, time and place of the works as entailed in them. Smithson did everything he could make this relationship necessary and unavoidable: his first move, with his turn from painting to sculpture, was to make works that “cancel themselves out”—The Eliminator (1965/66) and Enantiomorphic Chambers (1966)—but this canceling is double-edged, acceding to larger questions of meaning. These works, even at the time, depended on their ironic framing and generative meaning-making—an exterior syntax stemming from the works that would lead on to the next in a series. So the Spiral Jetty, in a precise sense, could be seen as a temporal/spatial extension of The Eliminator—on a larger scale that would still cancel itself out, viscerally inscribed in the bloody, cinematic syntax of the attending film. This generative movement leads, as the agency or Wirkung of the work, to its contextual “lore”—and therein lies a key element of her biography. Any artist, on whatever level, generates “lore” as a part of the meaning of their work; it is Boettger’s exemplary biocritical project to hardwire that lore to the work. Even in the most minimal or formal projects, that lore will exist; indeed, Smithson’s use of the term “entropy” to describe 60s minimalism anticipates the work’s choral breakdown in its Wirklichkeit. The Russian formalist Viktor Shklovsky wrote of “literary biography as a device”—but Smithson’s was more dimensional and reflexive; his lore had the property of material in its own right.

As convincing as is Boettger’s recovery of Smithson’s religious and homoerotic obsessions with the Christ image—a figure as she claims for the death of his brother Harold, which preceded his birth by two years—there are two major open questions. One—which would take a lengthy discussion of Smithson’s move from painting and iconology to sculpture and conceptual frames—is what motivated the 28-month gap between these two periods, a conversion experience to an ironic and secularizing framework that reinterpreted and displaced the cathexis onto the “image.” In the “turn to language” in writing, there would be a similar conversion away from image and any kind of holism or theology to focus on the material text as an open horizon of meaning. Would the deferred cathexis return holistically, to the level of the work? is a question to pursue in Language writing. The second open question is the relation of this decathexis in Smithson to the turn to language and, ultimately, to the form and necessity of his critical writing as poetics. This was remarkable, it must be noted—an outpouring of writing over a seven-year period that opened an entire new path for the making of art. It was this opening I perceived and responded to in my lecture at 80 Langton Street—the Wirkung of a “total syntax” that could frame a project in poetry. One question I would ask of Boettger, then, is what more can we learn about Smithson’s relation to poetry; what else had he read other than Four Quartets? What else was in his poetry library? Which poets did he know—not just those, like Peter Schjeldahl, who wrote about art? Who were his literary influences and contemporaries, other than Eliot, Borges, and J.G. Ballard?

As convincing as is Boettger’s recovery of Smithson’s religious and homoerotic obsessions with the Christ image—a figure as she claims for the death of his brother Harold, which preceded his birth by two years—there are two major open questions. One—which would take a lengthy discussion of Smithson’s move from painting and iconology to sculpture and conceptual frames—is what motivated the 28-month gap between these two periods, a conversion experience to an ironic and secularizing framework that reinterpreted and displaced the cathexis onto the “image.” In the “turn to language” in writing, there would be a similar conversion away from image and any kind of holism or theology to focus on the material text as an open horizon of meaning. Would the deferred cathexis return holistically, to the level of the work? is a question to pursue in Language writing. The second open question is the relation of this decathexis in Smithson to the turn to language and, ultimately, to the form and necessity of his critical writing as poetics. This was remarkable, it must be noted—an outpouring of writing over a seven-year period that opened an entire new path for the making of art. It was this opening I perceived and responded to in my lecture at 80 Langton Street—the Wirkung of a “total syntax” that could frame a project in poetry. One question I would ask of Boettger, then, is what more can we learn about Smithson’s relation to poetry; what else had he read other than Four Quartets? What else was in his poetry library? Which poets did he know—not just those, like Peter Schjeldahl, who wrote about art? Who were his literary influences and contemporaries, other than Eliot, Borges, and J.G. Ballard?

The stakes of reading Smithson as a Language writer in 1979, in any case, were high. The model of syntax would not only include the “inner” syntax of the work but would extend outward, in choral rings as it were, in an “outer” syntax. This dimension of the work could lead to a questioning of the boundaries of work and a fusion of horizons between genres and disciplines—exactly what the interdisciplinary project of 80 Langton Street and other artists spaces pursued in the productive period of the late 70s, when art needed to reorient itself to life on new terms. Smithson’s writing as a mechanism for the making of art were crucial to such an endeavor: hence what I would call not a “turn to language” but a “turn to poetics.” Within two years, I would begin a new project, Poetics Journal, with my co-editor Lyn Hejinian—who had her own reasons to expand the formal syntax of writing. That work was done over a two-decade period and has now been collected in our Guide to Poetics Journal. Would that its motives and necessity in the artistic and political contexts of its period be read! as they mainly no longer obtain (what follows after them, on what assumptions or models?). Boettger’s exegesis of Smithson’s unfolding oeuvre makes a model for expansive scholarship that does just that—creates new terms for comprehension and meaning-making.

The stakes of reading Smithson as a Language writer in 1979, in any case, were high. The model of syntax would not only include the “inner” syntax of the work but would extend outward, in choral rings as it were, in an “outer” syntax. This dimension of the work could lead to a questioning of the boundaries of work and a fusion of horizons between genres and disciplines—exactly what the interdisciplinary project of 80 Langton Street and other artists spaces pursued in the productive period of the late 70s, when art needed to reorient itself to life on new terms. Smithson’s writing as a mechanism for the making of art were crucial to such an endeavor: hence what I would call not a “turn to language” but a “turn to poetics.” Within two years, I would begin a new project, Poetics Journal, with my co-editor Lyn Hejinian—who had her own reasons to expand the formal syntax of writing. That work was done over a two-decade period and has now been collected in our Guide to Poetics Journal. Would that its motives and necessity in the artistic and political contexts of its period be read! as they mainly no longer obtain (what follows after them, on what assumptions or models?). Boettger’s exegesis of Smithson’s unfolding oeuvre makes a model for expansive scholarship that does just that—creates new terms for comprehension and meaning-making.

Notes and links

Texts: Suzaan Boettger, Inside the Spiral: The Passions of Robert Smithson (Minneapolis: U Minnesota P, 2023)

Nancy Holt, ed., The Writings of Robert Smithson (New York: NYU P, 1979)Lyn Hejinian and Barrett Watten, eds., A Guide to Poetics Journal: Writing in the Expanded Field, 1982–1998 (Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan UP, 2013)

Douglas Messerli, ed., “Language” Poetries: An Anthology (New York: New Directions, 1987)

Barrett Watten, 1–10 (San Francisco: This, 1989); collected in Frame (1971–1990) (Los Angeles: Sun & Moon P, 1997)

———. Total Syntax (Carbondale, Ill.: Southern Illinois UP, 1984)Notes: [1] In conversation in the early 80s, Ted Berrigan complimented my definition, saying it was the best account of “syntax” he had read. I then asked him if he knew the work of Roman Jakobson, and he said he did. Did he? one never knew what to believe coming from Berrigan; my sense, however, is that he did know the work of Alfred Korzybski as it was a cult classic among the Beats, especially William S. Burroughs.

Images: [1] Domain of the Great Bear by Robert Smithson and Mel Bochner, Art Voices (Fall 1966)

[2] Flyer for Barrett Watten residency, 80 Langton Street, San Francisco, 19–22 December 1979 (BW Archive)

[3] Cover of Total Syntax (1984)

[4] Robert Smithson, Christ Series: Christ Carrying the Cross (1960), Holt-Smithson Foundation (here)

[5] Cover of “Language” Poetries (1987). The use of Smithson’s Gyrostasis (1966) as cover art was surprising, and may have been inspired by my critical writing, which is discussed in the introduction, or Clark Coolidge’s Smithsonian Depositions/Subject to a Film (1980), or both