Grand Piano TV episode 6: Barrett Watten

original recording, 17 November 2022

take 2: 27 November 2022

The name “theoretical biography” is intended to distinguish its territory from that of philosophy and physiology better than before, and to expand that biological approach which has been one-sidedly paraded and, in part, greatly exaggerated by the most recent school of psychology (Darwin, Spencer, Mach, Avenarius). Such a science would have to account for the mental life as a whole as it progresses from the birth of an individual to his death according to certain laws, just as it does for the coming into being and the passing away, and all the discrete phases in the life of a plant.

—Otto Weininger, Sex and Character (1903)

Introduction: method/technique

[Original recording] I’ve been thinking about how to represent The Grand Piano in this reading. One thought was simply to take a section and read it straight through with comments, build a structure out of it—like the concept of “reading out” I spoke about the other day at the Kelly Writers House event, using the text as a platform to make more text, more interpretation. I decided not to do that; rather, I decided to sample from the text and let the text do the work of commenting on itself. (If you want to experience the section that I would have read straight through, you can go to The Grand Piano part 4 and read that section.) I’ve done quite a lot of “reading out” of The Grand Piano; in Questions of Poetics there is a whole chapter on it. Even as the work was coming into focus, not yet complete, I was giving lectures on it—the whole process was entirely immodest.

What I came up in my chapter still interests me: what is going on in our nonnarrative history with beginnings, middles, and ends—because in the way we wrote The Grand Piano we were disrupting any idea of a beginning and a middle and an end. I started looking at beginnings and where they were in the text. They are all over the place; in the last volume there are beginnings; they are distributed throughout. Beginnings are often associated with opening up a book—the first time we read a poem by by Zukofsky, or by Creeley, or by Gertrude Stein: the light dawned early. Beginnings could also be the first time meeting someone; notable readings or performances; events at the Grand Piano or other venues. Middles would be the site of the Grand Piano itself and the writing scene more broadly, the swirl of events we were in; it could also be our writing and reflecting on those events. But what counts as ends? At the time there was a lot of anxiety about how to end The Grand Piano, since it was open-ended. Obviously it had to end; we had decided to do ten volumes. What were its ends?

What I came up in my chapter still interests me: what is going on in our nonnarrative history with beginnings, middles, and ends—because in the way we wrote The Grand Piano we were disrupting any idea of a beginning and a middle and an end. I started looking at beginnings and where they were in the text. They are all over the place; in the last volume there are beginnings; they are distributed throughout. Beginnings are often associated with opening up a book—the first time we read a poem by by Zukofsky, or by Creeley, or by Gertrude Stein: the light dawned early. Beginnings could also be the first time meeting someone; notable readings or performances; events at the Grand Piano or other venues. Middles would be the site of the Grand Piano itself and the writing scene more broadly, the swirl of events we were in; it could also be our writing and reflecting on those events. But what counts as ends? At the time there was a lot of anxiety about how to end The Grand Piano, since it was open-ended. Obviously it had to end; we had decided to do ten volumes. What were its ends?

I wanted to rethink these categories. The other day in my talk on Larry Eigner at EMU I mentioned Bruno Latour’s Actor-Network-Theory, which could apply to The Grand Piano as well as to the work of Eigner. I was thinking, beginnings could be akin to “actor”: where there’s an agent of some kind. And middles could be a “network”: the social mix, mediation of all kinds, the imagined community. Writing The Grand Piano online was clearly a “network.” And then “theory”—end and “theory” might have an interesting relationship. The end of the project may not be a narrative end; it might be a theoretical ”upgrade” or advancement where one starts on a level plane of experience and makes theoretical claims for it.

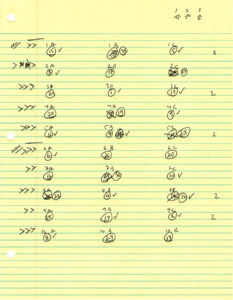

I decided to sample the work based on that tripartite division. What I did—and this is what I did this morning, today—I divided every section of my entries in The Grand Piano into three areas: beginning, middle, and end; or actor, network, theory. I tried to identify something in each section that worked with that division. It was rough and ready, and not exactly clear which was the most representative moment in each. Then I made a matrix as the structure of the reading as an event. Using aleatorical techniques such as a rolling a die, I made a sampling that would distribute the different categories across fifteen sections. In fact, I made thirty samples, but you’re only going to hear half of it—what you’re going to hear is matched by what you’re not going to hear, reserved for some time later.

In my recent reading for an essay on Gertrude Stein and repetition, I found a recent book on Stein—Sarah Posman’s monograph Vital Stein, on her relation to the nineteenth-century traditions of vitalism and historiography. In her chapter on The Making of Americans, an important nonnarrative history, she introduces Otto Weininger and his concept of “theoretical biography,” which he writes about in Sex and Character. Stein picked up on Sex and Character and used it in The Making of Americans, not only in the making of character “types” but in her breakthrough thinking about gender binaries that inform these types. The work itself can be seen as a “theoretical biography,” or what I have termed “an epic of subjectivation.” I found this passage from Weininger’s introduction to be interesting:

In my recent reading for an essay on Gertrude Stein and repetition, I found a recent book on Stein—Sarah Posman’s monograph Vital Stein, on her relation to the nineteenth-century traditions of vitalism and historiography. In her chapter on The Making of Americans, an important nonnarrative history, she introduces Otto Weininger and his concept of “theoretical biography,” which he writes about in Sex and Character. Stein picked up on Sex and Character and used it in The Making of Americans, not only in the making of character “types” but in her breakthrough thinking about gender binaries that inform these types. The work itself can be seen as a “theoretical biography,” or what I have termed “an epic of subjectivation.” I found this passage from Weininger’s introduction to be interesting:

All thinking begins with intermediate generalizations and then develops in two different directions, one toward concepts of even high abstraction, which encompass ever larger areas of reality by registering properties shared between ever more things, the other toward the intersection of all conceptual lines, the concrete complex unit, the individual, which we can only approach in our thought with the help of an infinite number of qualifications and which we define by adding to the highest generalization, a “thing” or “something,” an infinite number of specific distinguishing features.

Whether Weininger was a genius or a nutcase, he inspired Stein in The Making of Americans. I thought to begin with this notion of “intermediate plane of generalizations” and then see which way it’s going: upwards, or toward more generality, or downward towards more specificity. I can see The Grand Piano as written at the level of “intermediate generalization,” the intermedial level. That was my guide in thinking through my selection.

Herewith the results of my sampling from The Grand Piano:

15 Samples from The Grand Piano

1] Grand Piano 3: 86–88: “Correcting proofs. Of many moments of error and vulnerability.” > “Art as property: what a novel idea. An idea novels like Martin Eden were written to disprove.”

2] Grand Piano 9: 155–56: “In the indeterminate saga of social reproduction, prospective illusions unfold.” > “He cannot at once inherit the privileges of class and kind while remaining open to history nonetheless. Thus he is consigned to his fate, determined from the outset by the conditions of his birth—conditions that were circumscribed to begin with, as we find out.”

3] Grand Piano 2: 13–16: “I had hoped the comrade I was with would help in the cause of identifying the proper mode of work I should engage. ‘Labor’ was the imaginary.” > (skip 3rd paragraph) > “I remained outside it, fascinated but repelled, the better to interiorize the destiny of my class and kind. After we split she moved to Chicago, where she had some trouble with a fellow cadre, I later heard, before returning to our relationship for a last, brief period of intensity.”

4] Grand Piano 8: 155–57: “Whatever the turn to language might mean, it was also lived. I remember trying to capture the hybrid neutrality of everyday life in its most repetitive forms through a use of language that had been stripped of all associations.” > “At the intersection of Eighth and Division Streets, ‘Place Names’: ‘What I saw at the fire site’ was literally ‘what I have always thought and said.'”

5] Grand Piano 1: 18–19: “In that seminar, the original model as far I am concerned for all such seminars to come—the utopian reading group, the collective talk series, the poetics listserv in the sky—we read the modern epic, beginning with Pound, Williams, Olson, and ending with Robert Grenier’s A Day at the Beach . . .” > “I remember from that event the self-canceling nature of Grenier’s presentation, as well as the row of Iowa stalwarts sitting in the back—Marvin Bell, Donald Justice, Norman Dubie, Roger Weingarten—who snickered through the whole thing and thought Grenier had lost his mind.”

6] Grand Piano 6: 66–67: “Perhaps the problem with this—if not its demonstration in the pages of This, was that it did not capture the larger truth of Ron’s method, his way of writing sentence after sentence: the totality of poetic form. In being so mired in particulars, one may never see the horizon of totality, the bigger picture, the encompassing whole.” > (skip poetry quote) > “To what were we refusing to refer? Or were we more directly referring to a specific refusal—as an actually existing state of affairs?”

7] Grand Piano 5: 42–43: “Once, walking in a field in the Sierra foothills, I picked up a rock. One of many in a field of rocks, all of which were red, volcanic” > (skip 3rd paragraph in original recording) > “The fire explodes, sparks shower everywhere. In the middle of the ashes, a burned-out aerosol can—only trace of the night’s unrecoverable excess”; (take 2; read 3rd paragraph) > “Before the flowers of friendship faded, our talk faded down the wishful defiles of its imagined canyons. Friendship between come-on and lament.”

8] Grand Piano 10: 205–6: “The transmission of poetry is a passion unlike any other; I experienced that directly with Grenier. In one version, transmission occurs from poet to poet in a patrilineal descent, producing anxiety of influence as a by-product.” > “On one sheet with a penciled date of 1971, I find the following in large, childlike script: / Hello there Barry Watten / Why did I call you / late at night / as it were?”

9] Grand Piano 4: 79–80: ‘The authors are in eternity, but we were in everyday life. Under the aspect of . . . materiality?” > “Perhaps I wrote ‘Silence’ in the middle of the night, before having the dream I later remembered it as recording. I still think I will somehow recover the dream, from deep within the interior, to this day.”

10] Grand Piano 9: 119–21: “As for noise: on 14 January 1978, the Sex Pistols gave what was to be their last concert, at Winterland Auditorium. I remember the posters for the event, even an excited buzz at its approach . . .” > “I would have heard: ‘God Save the Queen,’ “E.M.I.,’ ‘Holidays in the Sun,’ ‘No Feelings,’ and ‘Pretty Vacant.’ My education would have begun right there.”

11] Grand Piano 5: 34–35: “Destructive envy. What writer doesn’t know what that means?” > (skip 2nd paragraph) > “An alternative, less controlling defense, more open to preserving the difference of what confronted one to begin with, would be to transform elements of alterity into a chain of identity that spreads outward and beyond. We may call this the politics of identification.”

12] Grand Piano 8: 165–67: “I would not stoop to allegory. If my motives were entirely clear to me, they would be to elaborate or put into play the terms by which a poetics may be constructed.” > “‘Her recording devices show only static.’ What really occurred is a matter for debate.”

13] Grand Piano 3: 98–100: “Between sex and work, there was writing, or so it seemed at the time. The point of writing this now is that there is an upgrading of oneself that should be discouraged, in terms of what motivated me then.” > (skip poetry quote) > “This is the moment when I commit that knowledge to the page. Let it not be erased; I want to think forward from that point to the next.”

14] Grand Piano 9: 178–79: “Believe me, I am a poet and professor. I inherited the chair of poetry from my noble predecessor, having been singled out from hundreds of job applicants.” > (skip 3rd and 4th paragraphs) > “Or is it the other way around? Professors are thought to teach what has already been accomplished, while poets and philosophers make their works and discourse on truth for all time.”

15] Grand Piano 1: 13–15: “I remember talking with the editor at UC Press who helped bring out ‘A’ and, later, the first book of Zukofsky criticism (which Ron immediately [panned] in Poetics Journal), about our production—particularly its opacity. She said, yes, it’s like my Jewish relatives—everyone trying to talk at the same time.” > “As I later wrote: ‘Our marriage domesticated the courthouse.’ This writing is his tombstone; we survived.”

Notes and links

The introductory text is edited and revised from the version in the original recording. The first recording was made in Gallery View, with the Speaker unpinned, and includes both the introduction and a lengthy discussion afterward. To correct the error, I made a second recording in Speaker View, with a minimal introduction. For both, click here.

Quotations from Otto Weininger’s Sex and Character are from Sarah Posman, Vital Stein: Gertrude Stein, Modernism, and Life (Edinburgh: U Edinburgh P, 2021), 000, 000. I also consulted Claudia Franken’s monograph on Stein and intellectual history in the process of writing for Expanded Poetry at the University of Porto, November 2022; Claudia Franken, Gertrude Stein, Writer and Thinker, Hallenser Studien zur Anglistik und Amerikanistik (Münster: Lit Verlag, 2000).

I wrote on The Making of Americans as a theoretical autobiography in “An Epic of Subjectivation: The Making of Americans,” Modernism/Modernity 5, no. 2 (Spring 1998): 95–121; online.

For all [ten t/k] episodes of Grand Piano TV, go to Barrett Watten Mode C (YouTube). For my brief note presented online at “The Grand Piano: Ten Years After” at Kelly Writers House, 2 November 2022, click here. To order one of the last 100 complete sets of The Grand Piano, click here.