Writing in the Event:

Writing in the Event:

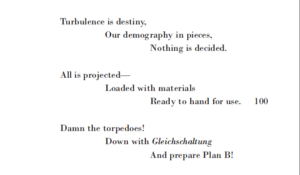

“The Beirut/Hell Remix

(After Etel Adnan)”

Last October I had the good fortune to preview Etel Adnan: Light’s New Measure, the Guggenheim Museum’s career retrospective of Adnan’s visual art, which makes significant reference to her writing. The cross-genre and multi-languaged aspects of her work could not be missed, an opening beyond the usual categories that art history and museum curating maintain. The museum was also making a political point in showing Adnan’s work along with a deep selection of the abstract painting of Vasily Kandinsky. The move from landscape to abstraction unites the two, but the differing contexts for abstraction are equally the point. Eurocentric modernism is in transition, refunctioned as a global cosmopolitanism, which arrives with the breakthrough moment of Adnan’s painting at dOCUMENTA 13 (2012) at what I have described as a “global archive.”

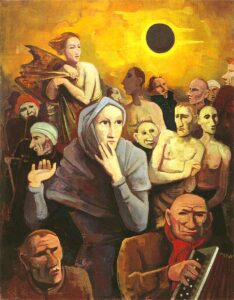

The occasion itself was compelling and bittersweet. Etel herself could not attend the opening but was represented by her partner, Simone Fattal—whose solo show at the Whitechapel Gallery in London was also on the global agenda. With Carla Harryman, we made plans to meet in Paris in November; we would have a French Thanksgiving, the day after the American one. Etel Adnan died on November 14, a Saturday. The news came through friends the next day. From all corners and all kinds of people the reaction was profound: the passing of a figure who had touched many, over many decades. We would still be coming to Paris as travel was arranged and plans had been made; the Omicron curtain had not yet come down. Everything was up in the air, suspended. Simone texted after we arrived; will you still be coming to dinner? Meetings with a remarkable woman on the rue Madame. We discussed everything and nothing as friends came and went. One resonant detail concerned Etel’s daily attention to events in Beirut, from economic collapse to the 2020 explosion. Not coincidentally, the Institut du Monde Arabe was exhibiting visual art referencing Beirut before and after the explosion under the title “Lumières du Liban,” in which Etel and Simone were both strongly present. We told Simone we would attend, and reported back after we did.

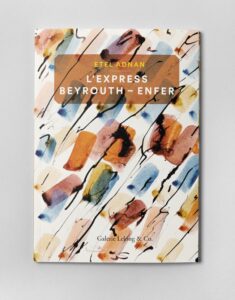

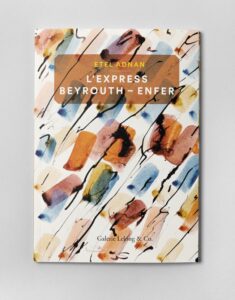

The museum bookstore stocks an impressive array of titles by Adnan, in many languages. I was immediately taken by Galerie Lelong’s 2021 publication of L’Express Beirut–Enfer, which brought together three texts, the first originally written in French and then later published in her English version. Meanwhile, plans that had been under way at the Guggenheim Museum were also up in the air, with the news of Etel’s passing, the onset of the Omicron surge, and the Guggenheim’s new partnership with the Academy of American Poets. In the end, I would agree to provide a written work, on commission, for the tribute to Etel, to be published online in conjunction with a virtual reading by poets who could perform in New York. Both events took place: the reading, while impeded by some gapping due to bandwidth issues, features an epochal performance by Anne Waldman along with tributes by Ammiel Alcalay, Omar Berrada, Stephen Motika, and Asiya Wadud, made available on Vimeo. And my text, “The Beirut–Hell Remix (After Etel Adnan),” along with an explanatory note that appears at the end of the poem, is published at the link below. One can only hope that, in future days, the many facets of this event for Etel Adnan will be seen together.

“The Beirut–Hell Remix (After Etel Adnan)” [link]

Original by Etel Adnan composed 1970; first published 1971

Adaptation/translation by Barrett Watten; completed January 2022

Online publication by The Guggenheim Museum, January 2022

Notes and links

[t/k]