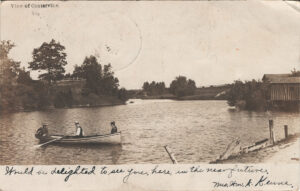

View of Centerville.

Would be delighted to see you, here, in the near future.

Mrs. Wm. A. Keune

[Hika Wis. Aug 17 1906]

Mrs. Emil Plantz, Milwaukee, Wis.

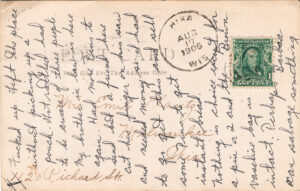

1120 Richard Str.Fucked up. Left the place

without picking up a

pouch. Got rattled had

to be aware of three people.

My brother in law is here

again. Had more Pins to

send but a friend here

cut his finger on his saw

and needed money so I had

to go get this and sell

some Pins to get

instant bread.

Nothing is choice except for

a pin or 2 and the Brown

vaseline bag is

intact. Perhaps Barbra

can salvage something.

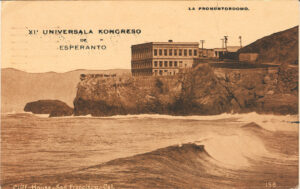

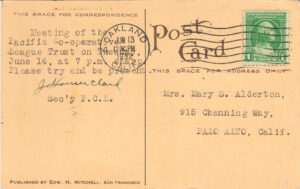

This messageless message is a find from my archive, preserved over 114 years. Sent from a Mrs. Keune to a Mrs. Plantz, it was then overwritten by someone in the family, likely my great grandmother Marion Starr Alderton, a socialist feminist and, later, Esperantist who publicly advocated multiple causes such as Suffrage and World Peace. The “pins” referred to in the text may have had some kind of political meaning. What stands out was the use of “fucked up” by a woman writing on the back of a postcard—possibly not intended to be mailed but used as a note card to family member or friend—at the early date of 1906. Fuck, as one learns from an entire chapter devoted to the word in Paul Fussell’s Wartime: Understanding and Behavior in the Second World War, was massively deployed during World War II, whence the acronym SNAFU: “Situation Normal All Fucked Up.” In literature, Norman Mailer attempted to use the word with the same frequency as was common at the time in his novel The Naked and the Dead but was forced to substitute the ridiculous sounding fug or fugging or fugged up. The import of the word’s class and gender politics led, in the 60s, to a legal battle over D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterly’s Lover, the Free Fuck Movement (a spinoff of the Free Speech Movement), the magazine Fuck You, and the band The Fugs (which I first saw at St. Marks Church in New York over Thanksgiving break in 1965). What can one make of this evidence—of its commonplace usage, by a woman in an everyday domestic setting, among contingencies that are lost to us? Compare this usage to the later massification of fuck, followed by its politics as a site for censorship or liberation. Michel Foucault would have a field day with the self-regulation that is the occasion of the word fuck in contemporary parlance, which extends to other issues of present concern about which I remain silent.

It is true that this reproduction of a reproduction (always a text and picture, indissociably) has limits, in in principle governed by a law and subject to copyright. you know that he has a kind of genius for unearthing post cards and for playing on them; he sent me one a long time ago with the motto “reproduction prohibited” printed on the border enframed. I never knew what he meant, if he wanted to draw my attention to the “general” paradox of the motto which he knew would interest me, or if he discreetly was asking me to be discreet and to keep for myself what he was saying, or rather barely suggesting in the said card. I have never been sure of what I thought I understood, the content of the information or the denunciation. Terrified, I projected into it the worst of the worst, it even made me delirious. [Derrida, Post Card, 37]

Notes and links

Derrida, Jacques. The Post Card: From Socrates to Freud and Beyond. Trans. Alan Bass. Chicago: U Chicago P, 1987.

Fussell, Paul. Wartime: Understanding and Behavior in the Second World War. Rev. ed. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1990.[Links t/k]