The way things are going

They’re gonna crucify me . . .

—John Lennon

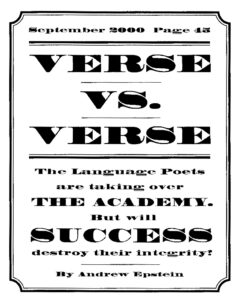

It is hard to move ahead, at this point in time, to the dark core of my archive with a straight face: I mean the awe-some spectacle of “Stalin as Linguist,” the apex of all literary hit pieces. And, as luck would have it, someone has gone and started the job for me. On 24 August 2018, Dispatches from the Poetry Wars hosted David Levi Strauss’s mini-dossier of the scandal that erupted in Poetry Flash over his 1985 revival of the 1978 debate with Robert Duncan over Louis Zukofsky, about which I have written so much I do not even want to link to it [but see below]. The capstone of the dossier is not Levi Strauss’s encomium, nor the original Poetry Flash slam, published over two full pages about the same time, but Clark’s 1987 version, cleaned up and published in Partisan Review. The stakes of the retrospective defense of Duncan (and belated attack on me) get past the local knee-capping to seek support from a serious piece of red-baiting, which, in the mid Reagan Era, still had resonance with neocons and would be taken up by them.

My charge is to find new take-aways from this old history, and there are several. First, Levi Strauss’s dossier, with Dispatches‘ minimal introduction, is mainly a scandal-provoking display, meant to complement the uploading of the Duncan tape as part of a long-term fascination with that event—not to gain any sort of understanding of it. But the dossier itself is bad history (sense 1: methods): the context for this privileged eruption of the Poetry Wars misses the larger stakes of the reception of Language writing, which was full-tilt at the time [see below]. As such it is a nostalgic bit of hagiography for Levi Strauss and the Duncan revival. Second, the scandal returns to what was so cryptic and provocative about the line “Stalin as a linguist” itself. What was its use in my poem, and what bad history (sense 2: events) does it refer to? What issues of authority, relevant to the present, does this second-order invocation of “Stalin” disclose? Finally, the publication of this dossier itself had a context, in fall 2018, that would become fateful quite soon—providing an example of the uploading of pseudo-scandalous material to target, abject, and humiliate. The dossier draws on the tradition of the journalistic hit piece and remediates it in the age of doxxing and trolling, for nefarious purposes to come. … More

My charge is to find new take-aways from this old history, and there are several. First, Levi Strauss’s dossier, with Dispatches‘ minimal introduction, is mainly a scandal-provoking display, meant to complement the uploading of the Duncan tape as part of a long-term fascination with that event—not to gain any sort of understanding of it. But the dossier itself is bad history (sense 1: methods): the context for this privileged eruption of the Poetry Wars misses the larger stakes of the reception of Language writing, which was full-tilt at the time [see below]. As such it is a nostalgic bit of hagiography for Levi Strauss and the Duncan revival. Second, the scandal returns to what was so cryptic and provocative about the line “Stalin as a linguist” itself. What was its use in my poem, and what bad history (sense 2: events) does it refer to? What issues of authority, relevant to the present, does this second-order invocation of “Stalin” disclose? Finally, the publication of this dossier itself had a context, in fall 2018, that would become fateful quite soon—providing an example of the uploading of pseudo-scandalous material to target, abject, and humiliate. The dossier draws on the tradition of the journalistic hit piece and remediates it in the age of doxxing and trolling, for nefarious purposes to come. … More