The way things are going

They’re gonna crucify me . . .

—John Lennon

It is hard to move ahead, at this point in time, to the dark core of my archive with a straight face: I mean the awe-some spectacle of “Stalin as Linguist,” the apex of all literary hit pieces. And, as luck would have it, someone has gone and started the job for me. On 24 August 2018, Dispatches from the Poetry Wars hosted David Levi Strauss’s mini-dossier of the scandal that erupted in Poetry Flash over his 1985 revival of the 1978 debate with Robert Duncan over Louis Zukofsky, about which I have written so much I do not even want to link to it [but see below]. The capstone of the dossier is not Levi Strauss’s encomium, nor the original Poetry Flash slam, published over two full pages about the same time, but Clark’s 1987 version, cleaned up and published in Partisan Review. The stakes of the retrospective defense of Duncan (and belated attack on me) get past the local knee-capping to seek support from a serious piece of red-baiting, which, in the mid Reagan Era, still had resonance with neocons and would be taken up by them.

My charge is to find new take-aways from this old history, and there are several. First, Levi Strauss’s dossier, with Dispatches‘ minimal introduction, is mainly a scandal-provoking display, meant to complement the uploading of the Duncan tape as part of a long-term fascination with that event—not to gain any sort of understanding of it. But the dossier itself is bad history (sense 1: methods): the context for this privileged eruption of the Poetry Wars misses the larger stakes of the reception of Language writing, which was full-tilt at the time [see below]. As such it is a nostalgic bit of hagiography for Levi Strauss and the Duncan revival. Second, the scandal returns to what was so cryptic and provocative about the line “Stalin as a linguist” itself. What was its use in my poem, and what bad history (sense 2: events) does it refer to? What issues of authority, relevant to the present, does this second-order invocation of “Stalin” disclose? Finally, the publication of this dossier itself had a context, in fall 2018, that would become fateful quite soon—providing an example of the uploading of pseudo-scandalous material to target, abject, and humiliate. The dossier draws on the tradition of the journalistic hit piece and remediates it in the age of doxxing and trolling, for nefarious purposes to come.

My charge is to find new take-aways from this old history, and there are several. First, Levi Strauss’s dossier, with Dispatches‘ minimal introduction, is mainly a scandal-provoking display, meant to complement the uploading of the Duncan tape as part of a long-term fascination with that event—not to gain any sort of understanding of it. But the dossier itself is bad history (sense 1: methods): the context for this privileged eruption of the Poetry Wars misses the larger stakes of the reception of Language writing, which was full-tilt at the time [see below]. As such it is a nostalgic bit of hagiography for Levi Strauss and the Duncan revival. Second, the scandal returns to what was so cryptic and provocative about the line “Stalin as a linguist” itself. What was its use in my poem, and what bad history (sense 2: events) does it refer to? What issues of authority, relevant to the present, does this second-order invocation of “Stalin” disclose? Finally, the publication of this dossier itself had a context, in fall 2018, that would become fateful quite soon—providing an example of the uploading of pseudo-scandalous material to target, abject, and humiliate. The dossier draws on the tradition of the journalistic hit piece and remediates it in the age of doxxing and trolling, for nefarious purposes to come.

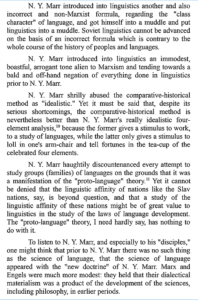

The series of covers of Stalin’s original work, and their historical contexts (late Stalinism and Maoism in the first two) remind us that references to “Stalin” are no joke (though the dark humor of the film The Death of Stalin [2017; dir. Armando Iannucci] is evoked by the third image). Screen captures of the third, reprinted edition locates two key tropes: Stalin’s argument, against the dominant linguistic school in Soviet Russia, that language is not a superstructure over a base (like literature, culture, and religion); and a violent smear campaign against Marr, the linguist who had made this “unscientific” claim, which may be the real purpose of this book. The historian Isaac Deutscher noticed the weirdness of its appearance in 1950, after five years in which Stalin perpetrated roughly half of the killings in the Gulag:

For about five years he made not a single public utterance (apart from a few trite interviews accorded to foreign journalists; but the journalists were hardly ever admitted to his presence; they received in writing his answers to his questions). When in the anxious early days of the Korean war he chose to make a pronouncement, it was on—linguistics. (Quoted in Gray, Stalin on Linguistics, 165).

The intellectual violence of this pronouncement and its circumstances, “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma” as had been said of Russia itself, evokes also the style of latter-day mystifiers, but in a hyper-realized, extreme form. Alexander Solzhenitsyn, in a chapter of The First Circle devoted to the episode, mocks Stalin’s musings and pretension insights:

Properly speaking, it’s like this: modes of production consist of productive forces and productive relationships. To call language a relationship is impossible. So does that mean language is a productive force? But productive forces include the instruments of production, and people. But even though people speak language, language is not people. The devil himself doesn’t know—he was at a dead end. (Quoted in ibid., 166)

What emerges, retrospectively, from this historical anecdote is its absurdity—mixed with terror, something we are experiencing right now without question. Interrogating the gap between language and terro, poetry and history, may indeed have been a motive for the use of the line—but without context, it is strictly undecided. As with the cosmos, it is turtles all the way down.

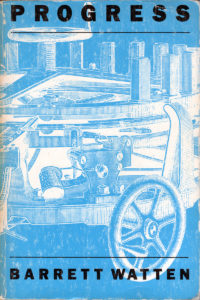

The question is, what was it about the line “Stalin as a linguist,” abruptly appearing on page 1, stanza 2 of the 1985 Roof Books edition of Progress, that caused this reaction? Returning to the edition itself suggests some interpretants. First would be the machinic image on the front cover—a reversal of a nineteenth-century printing machine before the invention of linotype, suggesting the materiality of productive relations but also the “crude mechanical access” of my reading of Zukofsky. The back cover, with an author shot that was, in fact, a passport photo—hence a kind of mug shot—appears above endorsements from Andrew Ross, Geoffrey Young, and Robert Creeley. The first two juxtapose political and aesthetic perspective on the work, while the latter—Creeley’s unsolicited response to Total Syntax—was likely the most provocative message of the three. The opening of the poem constructs a temporal sequence out of a series of mixed messages; not a collage or a composition but a substitute way of thinking, modeled on the “inner speech” of Soviet ideologist V.N. Voloshinov and psychologist Lev Vygotsky as much as on Viktor Shklovsky’s ostranenie. The framing of the poem offers some avenues to reading the poem’s opening by means of “Stalin as a linguist,” but what precisely are they? It is this gap or aporia of meaning that drove the hostile critics up a wall.

Levi Strauss’s dossier itself has a major gap in interpretation to close: between the defense of Duncan’s performance at the Zukofsky event (and his condemnation of mine) and the bullying and red-baiting of Clark’s 1987 Partisan Review piece. What joins them together, and connects the dots with “Stalin as linguist,” I think, is three things: questions of meaning and what guarantees it; anxieties about authority, either literary or political, as the necessary guarantee of meaning; and fear that authority, and its guarantees, are finally founded on violence. The demand for a guarantee for meaning entails some kind of violence, either intellectual, aesthetic, or political. Levi Strauss’s hagiographical return to the Zukofsky event needs to establish Duncan as the authority who guarantees meaning; hence the inflated reading of his performance and the denigration of the “crude mechanical access” of mine. But the effort was also based in present concerns: a defense of community around the New College poetics program, which Duncan founded two years after the SFAI event, in reaction to the social grouping of the Language poets, and with which Levi Strauss was identified. Clark was a central figure in that program; hence the jump to “Stalin as Linguist” seeks a violence that defines community and its limits. The “sweetness and light” of Duncan’s aesthetic, after Dante, depends on the “force till right is ready” of Clark’s politics, after Arnold. The third term was, supposedly, us—exiled from the poetic collectivity we had impertinently assumed. Aesthetic community is founded on the violence of exclusion.

It was not so simple, however. To counter the exclusion of aesthetic community, it is necessary to return to the complex “swirl of concerns” (the locution is Charles Bernstein’s) at work in the productive years from 1975–85. Levi Strauss’s hagiographical dossier leaves a lot of things out, particularly the growing critical response (and reaction) to Language writing from about 1980. The bibliography below complicates this tidy narrative, opening up numerous questions. Critical reactions to Language writing were many, from Steve Abbott’s supportive but ambivalent reviews to Bruce Boone’s queer Marxist critique (“Language Writing: The Pluses and Minuses of the New Formalism”) to the reactionary stances of Kenneth Warren (“Language and Its Meaning”; here) and Geoffrey O’Brien (“Meaningless Relationships: Banging Against the Edge of Language”). More proximate to the Duncan/Clark axis of Levi Strauss’s dossier are two key elisions: the first is George Lakoff’s review of Writing/Talks, edited by Bob Perelman, which laid out a series of framing concepts from linguistics (the concept of “frame” among them). The second is the original version of Clark’s “Stalin as Linguist,” appearing the month after Levi Strauss’s revival and Lakoff’s review—and clearly motivated by the account of authority and authoritarianism put forward by Lakoff, which bears quoting:

Authors have the power of characterization—or the power to cede it to readers. That is one reason why there is so much concern in this volume with the role of the author and with autobiography. “Author” and “authority” come from the same source. An author has authority simply by virtue of being an author. How an author uses that authority matters. Barrett Watten focuses on the author-authority issue in the later poems of Olson’s The Maximus Poems. Olson was a huge, towering man, who projected his size into his poems in various ways. One was by taking the name Maximus, despite having no real interest in the original Maximus of Tyre. This began as an interesting imposition of a historical frame that eventually took over the entire work and became boring. The reason was that authority itself became the central concern of the poetry. Instead of being just an author, Olson became an authority. His “uninterrupted statement,” Watten argues, is a projection onto form of his overwhelming authority problem. (“On Whose Authority”)

While the account of Olson is perfunctory, this passage is a productive nexus of many concerns. Lakoff’s critique of authority was provocative for Clark, to the extent that he saw it as an instance of violence, because it threatened his self-understanding as author, and he responded in kind. Later, he would go on to write a controversial biography of Olson, but for now his reaction was a two-page large format screed, throwing in the kitchen sink and the baby out with the bath water, that Levi Strauss fails to mention. The article is too large to fit on the platen of my scanner, and I have little interest in scanning it in any case, but I can provide a cell phone shot to indicate its abuse of the space provided it by Poetry Flash [here and here]. The excess of Clark’s piece ia an instance of violence in textual form, a simulacrum of the “originary” violence that guarantees meaning perhaps. And it was received as such: it unleashed a burst of collective triggering, evident in the many distressed letters to the editor that followed. Seeing success in his endeavor, Clark cleaned it up and sent it to Partisan Review, whose residual anti-Stalinism was likely beguiled by its red-baiting title—this is the document Levi Strauss provides. Then a second, even more scurrilous piece of Language-inspired red-baiting appeared from Stephen Schwartz, titled “Escapees in Paradise,” which pushed the reference to Stalin into a purported defense of Pol Pot [here]. What occurred in this brief nexus was, in any case, not for the faint of heart; the anxiety it released far outweighed anything like a literary or even political debate; what was produced was fear.

The literary history of that period, and its importance for the present, has not yet been written. It is not simply a literary history, but part of an attempt to understand the larger political and cultural dynamics of the world we are inscribed within. A larger implication for this history is the relation of violence to community, the need for exclusion based on a politics of fear. The real conditions of anxiety we are now living are even more desperate; we may take some lessons from these early attempts to comprehend them.

Bibliography, notes, and links

Note:

Sweetness and light: a phrase popularized by the nineteenth-century English author Matthew Arnold; it had been used earlier by Jonathan Swift. According to Arnold, sweetness and light are two things that a culture should strive for. “Sweetness” is moral righteousness, and “light” is intellectual power and truth. He states that someone “who works for sweetness and light united, works to make reason and the will of God prevail.” (Online source)

Force till right is ready: “Joubert has said beautifully. ‘C’est la force et le droit qui reglent toutes choses dans le monde; la force en attendant le droit.” (Force and right are the governors of this world; force till right is ready.) Force till right is ready, and till right is ready, force, the existing order of things, is justified, is the legitimate ruler. But right is something moral, and implies inward recognition, free assent of the will; we are not ready for right,—right, so far as we are concerned, is not ready, until we have attained this sense of seeing it and willing it.” (Matthew Arnold, Culture and Anarchy; online source)

Bibliography: Poetry Wars, 1981–87 (work in progress)

1981

Abbott, Steve. Notice of Grand Piano reading series. Poetry Flash (February).

———. “Un-Handling Romanticism: A Renewed Lyricism.” Review of Waltzing Matilda and How Spring Comes by Alice Notley and Primer by Bob Perelman. Poetry Flash (October).

Boone, Bruce. “Language Writing: The Pluses & Minuses of the New Formalism.” Soup (ed. Steve Abbott) 2: 2–9.

Linenthal, Mark. “Living Language.” Review of “Talks” issue of Hills, ed. Bob Perelman. Poetry Flash 100 (July).

Schjeldahl, Peter. “Cabin Fever.” Review of Subject to Fits by Geoffrey Young, My Pleasure by Laura Chester, Bay Area Language writing, and other works. Parnassus (Spring/Summer): 284–300.

Silliman, Ron. “Modes of Autobiography.” Review of So Going Around Cities by Ted Berrigan, My Poetry by David Bromige, and My Life by Lyn Hejinian. Ibid.: 41–45.1982

“Focus: Non Syntactical Writing.” Review of Wobbling by Bruce Andrews, The Busses by Steve Benson, and Own Face by Clark Coolidge, by Fanny Howe; review of Tjanting by Ron Silliman, by Michael Davidson; review of Ready to Go by Tom Mandel and Primer by Bob Perelman, by Thomas Meyer. American Book Review 4, no. 6 (September-October).

Fraser, Kathleen. “Partial Local Coherence . . Regions with Illustrations: Some Notes on Language Writing.” Ironwood (Tucson; ed. Michael Cuddihy) 20: 122–39.

Messerli, Douglas. “Wordscape Artists.” Review of Primer by Bob Perelman; Wobbling by Bruce Andrews, and Stigma by Charles Bernstein. Voice Literary Supplement (May): 10.

Price, Larry. “Directing the Text.” Interview with Alan Bernheimer, Eileen Corder, and Nick Robinson on San Francisco Poets Theater. Poetry Flash 116 (November): 1–2, 8–9.1983

Abbott, Steve. “Language & Sex Are Both About Power.” Review of “Urban Site” literature program and site-specific exhibitions. [Publication t/k].

Clark, Tom. “The Subject Is Language.” Review of Back to Forth by Gloria Frym and Four Lectures by Stephen Rodefer. San Francisco Chronicle (19 October).

Gleeson, Ann. “Tjanting in the Metro.” American Poetry Archive News.

Hollander, Benjamin. “A Marriage of Poetry, Music & Mathematics.” Review of Zukofsky’s “A”: An Introduction by Barry Ahearn. San Francisco Chronicle (5 July).

LaVoie, Steve, and Pat Nolan. “Proclamation in Declaration of Voluntary Exile.” Crime of Life: Newsletter of the Black Bart Poetry Society-in-Exile.1984

Middleton, Peter. Review of 80 Langton Street Residence Program 1982, ed. Renny Pritikin and Barrett Watten, and The L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E Book, ed. Bruce Andrews and Charles Bernstein. Reality Studios (ed. Ken Edwards) vol. 6, Interface: 84–90.

O’Brien, Geoffrey. “Meaningless Relationships: Banging Against the Edge of Language.” Review of The L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E Book ed. Bruce Andrews and Charles Bernstein; Code of Signals: Recent Writings in Poetics ed. Michael Palmer; Resistance by Charles Bernstein; ABC by Ron Silliman; Defenestration of Prague by Susan Howe. Voice Literary Supplement (April): 8–9.1985

Abbott, Steve. “Who Speaks for Us—An Answer to Laurie Price.” Poetry Project Newsletter (March).

———. Comments on Steve Benson and BW. Poetry Flash (t/k).

Anderson, Roger.”Language Poetry: Trouble in Verse Land, Part Two.” Daily Californian (9 October): 12–13.

Atlas, James. “The Literary Life in San Francisco.” Vanity Fair (November): 42, 45.

Clark, Tom. “Stalin as Linguist.” Poetry Flash (July): 5, 11.

“Flashback.” Letters responding to David Levi Strauss, “On Duncan, Zukofsky, & Film” by Ron Silliman, Jacqueline Cantwell, and Stephen Rodefer. With “Some Information” by Joyce Jenkins. Poetry Flash 136 (July).

“Flashback.” Letters responding to Poetry Flash 136 by David Levi Strauss, Dawn Kolokithas, Darrell Gray, Duncan McNaughton, Alastair Johnston, and Stephen Rodefer. Poetry Flash 137 (August).

Gilbert, Jack. “The Craft of the Invisible.” With a letter to the editor by Michael Davidson and response by Gilbert. Ironwood (ed. Michael Cuddihy) 24 (t/k): 156–77. FILE XER

Lakoff, George. “Hit Man Among the Poets.” Poetry Flash (t/k).

———. “On Whose Authority?” Review of Writing/Talks, ed. Bob Perelman. Poetry Flash (June).

LaVoie, Steve. “Monuments to Self-Pity.” Life of Crime Newsletter, ed. LaVoie.

——— and Pat Nolan. “The Attempted Assassination of Ted Berrigan.” Life of Crime: Newsletter of the Black Bart Poetry Society.

Price, Laurie, “Signed, Bored & Pissed Off in S.F.” Poetry Project Newsletter (February): 4.

Schwartz, Stephen. “Escapees in Paradise.” The New Criterion (December).

Strauss, David Levi. “On Duncan & Zukofsky on Film.” Poetry Flash 135 (June).1986

Abbott, Steve. “Silliman’s Phoenix: A Bird of ‘Paris Dyes.’” Review of Paradise by Ron Silliman and The Difficulties Silliman issue. Poetry Flash (December).

Bernstein, Charles. “The ‘language poets.’” Letter to the editor responding to Stephen Schwartz, “Escapees in Paradise.” New Criterion (February): 86–88.

Clark, Tom. “Another Look at ‘The Tree.” Review of In the American Tree, ed. Ron Silliman. San Francisco Chronicle (12 October): 14–15.

Creeley, Robert. “From the Language Poets.” Review of In the American Tree, ed. Ron Silliman. San Francisco Chronicle, September.

Kamiya, Gary. “The Great Language Poetry Debate.” Berkeley Monthly (December).

“L=I=N=G=U=I=Ç=A: A Homage to Barrett Watten . . . .” N.p.: Red Hill Press/Invisible City.

Melnick, David. “New Language of the Muses.” Review of Paradise by Ron Silliman, Precedence by Rae Armantrout, Central Europe by Tom Mandel, and A Reading 1–7 by Beverly Dahlen. San Francisco Chronicle Review (6 April): 5.

Silliman, Ron. “Language, Realism, Poetry.” Introduction to In the American Tree. Ed. Silliman. Orono, Me.: National Poetry Foundation. Xv–xxiii.1987

Benson, Steve. “Ganging Up on a Gang that Isn’t a Gang.” Letter to the editor responding to Gary Kamiya, “The Great Language Poetry Debate.” Berkeley Monthly (January). FILE XER

Byrd, Don. “Language Poetry, 1971–1986.” Review of In the American Tree, ed. Ron Silliman and “Language” Poetries, ed. Douglas Messerli. Sulfur (ed. Clayton Eshleman) 20: 149–57.

Carroll, Jon. “The Last Word in Literary Magazines.” Review of Zyzzyva, ed. Howard Junker. San Francisco Chronicle (4 September).

Clark, Tom. “Stalin as Linguist.” Partisan Review (June).

Duff, Michael. Review of In the American Tree, ed. Ron Silliman and “Language” Poetries, ed. Douglas Messerli. Small Press (October): 72–73.

Edwards, Ken. Review of In the American Tree, ed. Ron Silliman. Reality Studios (ed. Edwards) vol. 9: 87–90.

Guenther, Charles. “Poets Finding Unique Voices.” Review of “Language” Poetries, ed. Douglas Messerli. St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 10 May.

Kolokithas, Dawn. “It’s Hip to Be Right.” Review of The First World by Bob Perelman. Poetry Flash (August): 1, 6–7.

Leider, Emily. “Her Favorite Device Is the Echo.” Review of My Life by Lyn Hejinian. San Francisco Chronicle (18 October): 8–9.

McGann, Jerome. “Language Writing.” Review of In the American Tree, ed. Ron Silliman, and “Language” Poetries, ed. Douglas Messerli. London Review of Books. 15 October.

Messerli, Douglas. “Introduction.” “Language” Poetries. New York: New Directions. 1–11.

Mobilio, Albert. “Size Matters: Long Poems Strike Again.” Review of The Great Dimestore Centennial by Don Byrd; Word of Mouth by Ted Greenwald; and Tabula Rasula by Jed Rasula. Village Voice (11 August): 47.

Raffeld, David. Reviews of “Language” Poetries ed. Douglas Messerli and 21 + 1 American Poets Today ed. Emmanuel Hocquard and Claude Royet-Journaud. Art & Artists (October/November).

Scobie, Stephen. Review of “Language” Poetries ed. Douglas Messerli. The Malahat Review 79 (t/k).Links:

[t/k]