“Conduit” (“Kanal svyazi”)

trans. Arkadii Dragomoshchenko and Vladimir Feshchenko

Vsealizm (Moscow), 11 February 2024

From Moscow, for the second week in a row, comes a new translation of my work into Russian—here, “Conduit” into “Kanal svyazi”—in preparation for a bilingual edition to appear, one hopes, later this year. This work, brought forward over decades and across continents, truly stands as a conduit in the distressed conditions of communication, between the “territories of the East” and the rest of the world assuredly, but more generally as “what we live.” As I wrote on receiving word of this wonder:

There was a line from a Poets Theater play, Third Man by Carla Harryman, early 80s, spoken by Eileen Corder: “Go ahead, Moscow—I’m listening!” That was transgressive in the Reagan Era; in the current moment, one listens carefully to say the least. And now this translation of my poem “Conduit” has appeared—it is all about receiving messages, and not letting them stand as commonplaces or placeholders but as samples of “systematic distortion.” It’s about the “systematic distortion” of communication as communication itself, which we experience every day.

“Systematically distorted communication” is a term for living within reified postmodernity, a key concept for Jürgen Habermas, who laments the failure of transparency as a condition of the modern world at the end of Enlightenment and its lost promises. In the poem, I explore this condition through an article that was much on my mind, along with other Language writers in the 80s: “The Conduit Metaphor: A Case of Frame Conflict in Our Language about Language” by Michael J. Reddy. For Reddy, systematic distortion is not so much a product of (post)modernity but a constitutive part of language itself, due to a meta-concept about meaning in which what is to be communicated—”the message”—is put into a container of some kind (think of pneumatic tubes in office buildings) and sent to its destination, where it is unpacked. This metaphor of meaning as an object sent through a conduit leads to all kinds of misunderstanding, first because contexts embedded in the communication are not identical to those at the receiving end. The objectification of communication, even worse, leads to hardening of mistranslation between poles. In two epigraphs to the book Conduit (Gaz Press, 1988), I figured that at both ends of a spectrum of meaning:

As for me, I would say that a true poet is someone with an overwhelming urge to say something, to communicate some emotion, that . . . he will never forget what he wanted to say, and he will eventually end up by saying it, by having it accepted as evidence. —Francis Ponge, The Power of Language

In the end, A, B, C, and D all came privately to the conclusion that the others had either become hostile or else gone berserk. Either way it did not seem to matter much. None of them took the communications system seriously any more. —Michael J. Reddy, “The Conduit Metaphor”

At the time of writing, the late ’80s, this failure of communication where “all came privately to the conclusion that the others had either become hostile or else gone berserk” applied first and foremost to the poetry world. It was true both of the avant-garde (trying to send a message about messages) and for its populist detractors (who rejected the message as nihilism of some kind). The record shows this distortion of communication to be absolutely berserk—this was the period of the Poetry Wars, about which I have written at length (see here and linked posts). But this was also the time of the Neoconservative attack on the arts themselves, accelerating at the end of the decade with Sen. Jesse Helms and the New Right. That history still needs to be told for the devastation it wreaked on poetry, the arts, even the academy—and the compensatory choices many of us made then.

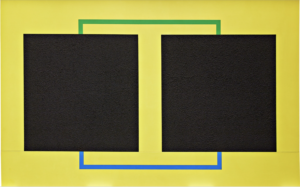

What seemed like solace in that period, on the other hand, was the rise of new art in the ’80s that both attempted commodity critique (Haim Steinbach, Jeff Koons, Sherrie Levine, the curators Collins and Milazzo) and explored new forms of abstraction that intersected with conceptual frameworks. My favorite artist from this period was Peter Halley—I simply liked his work, both for its use of bright, nonnaturalistic, industrial colors and geometric motifs that were given a faux symbolic value but which achieved a kind of productivity—a poetics one may say. It was this halb-symbolism I found most inspiring: a kind of conceptual thumbnail of social modernity that one could import into other conceptual (mis)understandings, with a fair degree of Witz. In the poems in Conduit and in the later poem “Frame,” I often used this concept of “thumbnail” symbolism or metaphor, often drawn from one-liner crunches of works of visual art I had seen or mini-narratives that I wanted to reduce to an aphorism:

from CONDUIT / I

An arrival in history only coincides with defeats.

The invisible body is a mirror of containers. Perfected, a chain of commands speaks.

Every road ends in an object. Unfolding, a world of parts in a display of same.

A sign revealed in buses for the driver or deportee.

Each utterance is unique only in a theory that specifies a point in time and space.

Then all the pawns fall.

While a model faces perception. Behind every survival is a whole totality of words.

I.e., parenthesis it is a text. To answer a question in runic workings of quotations behind which passion slips.

And left, imagining a sum: an I inverted to an it.

At the same time as an impostor. (156–57)

That an “I” could be inverted to an “it” is one of the motivating percepts of the poem—systematically distorted communication turns the speaker into an object, a prime example of reification. But I was also looking at pleasurable effects in lining up the various evidence of this distortion; by make a work of art out of it, one could arrive at pleasure or solace if not understanding. And that is pretty much what happened, even as the literal evidence—most of the edition of Frame (1971–1990) published by Sun & Moon Press—vanished in some kind of industrial accident or insurance write-off, I never found out which. One could say that, for any number of reasons, the message did not transmit from sender to receiver; the message was not received. But now this translation comes, across the bridge of space and time. Let us see in the translators’ words how it was comprehended:

Barrett Watten’s poem “Conduit” was first published in 1986 in the American journal Temblor and later in a separate book, Conduit, in 1988. It is a testament to the interest of “language writing” in communicative and cognitive theories in linguistics. In particular, the text is based on the metaphor of language as a “conduit” or “channel of communication” described in linguist Michael Reddy’s influential article “The Conduit Metaphor: A Case of Frame Conflict in Our Language about Language” (1979). Watten’s poetic text is constructed and read as an experiment in cognitive linguistics and poetics—with its semi-artificial sentences and semantics of constant shifts of focus. In these shifts, however, the reader can detect the operation of the purely poetic function of language, when the message turns on itself and begins to generate extraordinary meanings.

Arkady Dragomoshchenko’s archive preserves a translation of fragments of this text that he made back in the late 1980s. Two of these fragments were reproduced in the anthology of the newest poetry of the United States From Black Mountain to Language Writing (2022, New Literary Review, ed. Vladimir Feshchenko and Ian Probstein). The complete translation of the poem “Conduit” is published here: parts I, II, XI, XIV, XV, XX are translated by Arkadii Dragomoshchenko; the remaining parts are translated by me (Vladimir Feshchenko). A bilingual of selected works by Barrett Watten is currently being prepared for publication in the POLYPHEM publishing house.

I would like to superimpose the pleasure of this received communication with the alternately dark and bright surfaces, and uncanny connection, of Peter Halley’s Two Cells with Circulating Conduit (1986), reproduced above. The work was recently auctioned by Sotheby’s in the 100–150K range; we are talking about a different economy. With the Russians, I see value in the communicative act, or its attempt and critique: from one dark box to another linked by the tenuous means we undertake.

Notes and links

Image: Peter Halley, Two Cells with Circulating Conduit (1986); linked here, with short article and bibliography.

Texts: Barrett Watten, “Conduit,” in Conduit (San Francisco: Gaz Press, 1980). Cover by author.

———. “Conduit,” in Frame (1971–1990) (Los Angeles: Sun & Moon Press, 1997), 157-78.

———. “Kanal svyazi” (Conduit), trans. Arkadii Dragomoshchenko and Vladimir Feshchenko, Vsealizm (Moscow), 11 February 2024; here.

———. “Zavershjonnaya mysl” (Complete Thought) and “Plazma” (Plasma), trans. Ruslan Mironov, Vsealizm (Moscow), 5 January 2024; here.Note: modified DeepL translation of note.