For nearly all our originality comes from the stamp

that time impresses on our sensibility.

—Baudelaire, “The Painter of Modern Life”

My title is an oxymoron, as there is no “absolute” in the process of “psychohistory.” But to recall Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe and Jean-Luc Nancy’s The Literary Absolute, there is a historical relation of the psychohistorical to the emergence of the literary as an unfolding horizon of meaning, which they describe in the use of the romantic fragment in The Athenaeum. That tradition leads to Hegel’s preference for romantic art as best because it is always incomplete, thus demanding completion, and on to the hermeneutics of Hans-Georg Gadamer and the Konstanz School, with Hans-Robert Jauss and Wolfgang Iser. The concept of horizon, which is everywhere in my critical work (and in the title of my UC Berkeley dissertation Horizon Shift), unites an historical openness of interpretation with the ground of the events of psychic history. Today, for instance, is Martin Luther King’s birthday, and in an online post I recalled hearing the news of his death: “I was in sociology class, junior year, UC Berkeley, taught by Robert N. Bellah, when Martin Luther King’s assassination was announced in class—an event that would puncture the world view of liberals like him. He was, however, eloquent in tribute and memorable.” The meaning of that event was both historical and psychic, and it unfolds, for me and arguably all of us, in a horizon at once open and changing. It was, in short, psychohistorical; it remains so, and the way that it does grounds the horizon of its further interpretation.

I begin this lofty discussion as an attempt to respond, in the manner of “higher criticism” and not the kind of digital street action that is so often the case, to Tyrone Williams’s recent essay “Examples Of: On Barrett Watten’s Questions.” Tyrone’s review, unlike other recent ones, focuses on the “metacritical” stakes of writing about poetry and poetics in several senses: the nature of objectivity and the position of the poet/critic; the question of legitimacy in valuation and interpretation; and finally the nature of the “literary” and whether it is circular in terms of the selection, evaluation, and interpretation of the examples that define it. Language writing, thus, is for him an example of what counts as “the literary” in an absolute sense, or if not an absolute one at least one that is tendentiously proposed only to be legitimized in a book of literary criticism in a way that risks circularity. In his sense, Questions of Poetics is a defense of Language writing that, by its own terms of discussion, confirms it. And if this is the case of any work of literary criticism, it is a specific vulnerability with my own in that I was a participant in the rise of the form of literariness called “Language writing,” as simultaneously poet, publisher, organizer, and now critic.

At stake in both Questions de poétique and Questions of Poetics is the contested category of the “literary” and its relationship to the larger domains of aesthetics and history. Insofar as Jakobson’s and Watten’s interrogations presuppose the “end” of poetry’s claims to a general autonomy bequeathed by a history of cultural productions attenuated within the restrictive economy of the “literary” (even as those claims still support the flourishing “business” of poetry), they remain interested in its relative autonomy—that is, what, today, makes poetry, poetry—and its relationship to poetics within and beyond poetry. (Williams, “Examples Of”)

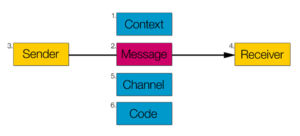

Tyrone begins his discussion, and to an extent ends it as well, with a parallel between my title and Jakobson’s to suggest a mutual effort to define the literary, and complicate it in terms of history, that finally risks a form of “circularity” between example (poetry) and concept (the literary). The difference between my work and Jakobson’s, it must be said, is in the different stakes of language, with the latter’s foregrounding of “the message for its own sake” as the “poetic function.” If I ironically invoke Jakobson—and this was the intent in calling him up—it is to suggest that my notion of poetics is anything but a language-centered structuralism (however much I learned from it and applied it, particularly, in writing on Larry Eigner in Total Syntax). Rather, poetics in my usage triangulates text, history, and theory in a way that does not make immanent, structural claims but historical, interpretive ones. If my method is hermeneutic, the question is whether it is circular. In one reading of Tyrone’s essay, the difference of history and textuality (and the key concept of “radical particularity”) risks being absorbed right back into “Language writing” as a form of totalizing literariness, seen as the old school would have it as context-independent and autonomous. This is a mistake in reading Language writing and has been from the beginning; the mistake itself identifies the faultline in its reception between literary (Perloff; literary reception before 2000) and critical (Hartley, historicist/culturalist critiques after 2000). Timothy Kreiner’s recent Marxist/materialist essay “Language Writing and the Subject of History” shows the continued viability of the latter, critical approach, with the waning of the merely literary.

The invoking of the hermeneutic circle, then, begs the question of the historical and cultural that is the throughline of my poetics, and why they are entirely different from Jakobson’s. For Jakobson, the “poetic” is the dominant linguistic function in poetry; other aspects of communication exist but are subordinate and relative. In unpacking the New Critical lyric as a form of sublime object or antagonistic kernel, I want to show how other aspects of the total communication system (as in Jakobson’s schema above) are constitutive elements that introduce a nonidentity (in Adorno’s sense) that expands outward in the act of interpretation to make new meaning, as a historicist poetics. This is a question not merely of “context” or even “channel” or “code” (which could mean history, genre, or discourse) but of an activated entailment of each of the four elements in each other. That is why I see the dyadic “object” as produced by the poet/critic as gendered—first in a normative, Oedipalized sense of a form of mastery over affect, then as a kind of postmodern “parthenogenesis” that attempts to erase gender dynamics in a mode of production of self out of self. Even Language writing could be informed by this gender dysphoria—but it most certainly is not, given the proliferation of women Language writers who do not dissociate gender from text. The poet/critic, for me, develops and enacts a necessary difference between the poetic or textual and its constitutive elements, which with Cultural Studies are captured by the three critical keywords race, class, and gender. My readings of the prose texts of Lyn Hejinian and Nathaniel Mackey, along with my writing on the assembly line in Detroit, are meant to show an expansive hermeneutics that opens and requalifies the poetic and literary. Rather than a circular return to Language writing, I show it in a process of change, as it is.

The horizon I want to return to here is the psychohistorical, which like the psychosexual leads to forms of outwardly expanding interpretation, fantasmatic horizons of meaning that continue because they are motivated. The name for that motivation in Questions of Poetics is right on the cover, the question of what motivates the making of Language writing as the productive consequence of itself. But I am also aware of, and interested in, the motivation of Tyrone Williams’s question of his review. Surely it is not merely to give a report on, as one may say, “how goes it with Language,” or even to question its influence. The larger question, I think, is the relation of the circularity—and thus the self-protectedness—of the literary in relation to exposure and vulnerability of the historical. On the one hand, then, I see a perplexing connection of the avant-garde Language movement with the conservative and institutional New Critics that evokes “literary criticism” itself as a mode of cultural control and even oppression. I wonder if Tyrone encountered that form of literary criticism at an earlier moment of literariness at Wayne State University, where he received his doctorate just a few years before I arrived on the scene. And I wonder too if the stress of the psychohistorical that comes through Questions of Poetics does not also register my moment of arrival in Detroit, where apart from a cruiser-class English Department, I found a cultural environment completely unfamiliar with the literary avant-garde. In reading Tyrone’s review as a conversation between these two moments, I welcome a rethinking of what counts as “literary criticism,” even though most poets or critics I know have long since stopped thinking in those terms. But they may be recast in the present moment as well, toward the end of asking truer questions of our motives than the merely evaluative. The larger question may indeed be an encounter between the English Department and Detroit, as a ground for rethinking the literary.

Image (top): Joseph Sima (Czech surrealist painter), untitled, date unknown. Reproduced from Roman Jakobson, Huit questions de poétique (Paris: Seuil, 1977); pdf here.

Image (center): the six functions of communication according to Jakobson; from “Roman Jakobson,” Wikipedia; link here.