Launch of Barrett Watten,

Not This: Selected Writings

Voznesensky Center, Moscow

46 Bolshaya Ordynka Street

January 24, 2025

The meeting focuses on how American literature experienced a “turn to language” in the 1970s, what the hybrid genres of contemporary poetry are, and the challenges faced by translators working with the “language trend” in literature. (Voznesensky Center announcement)

On the given date, at about 11:30 A.M. from a Detroit suburb, I was transported behind the lines of antagonistic states for a literary evening that, I hoped, would have long-term cultural and political meaning. It was not the first time had I stepped over this line, as I did for our “Summer School” in then-Leningrad, 1989, about which much has been written (including the multi-authored text published in 1991; here). Twenty-seven years later, with Carla Harryman, I traveled to now-St. Petersburg to participate in the Dragomoshchenko Prize awards in 2016. The consequences of these transpositions, as they may be called, between literary and cultural/political realities, continue to expand and be productive as sites of meaning. The turn to language turns out to be more than one thought.

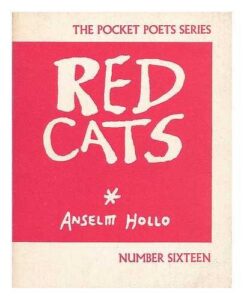

Although I am not well acquainted with Andrei Voznesensky’s entire career, I have just caught up with it on Wikipedia: here. What I generally knew was that he was a semi-official/official poet of the period of liberalization known as “The Thaw,” who served as a poetic ambassador to poets in opposition elsewhere; in the U.S. this would be Allen Ginsberg and Robert Lowell, an American parallel to the unofficial/official faultline of that period. City Lights Books published a “Pocket Poets” mini-anthology titled Red Cats (translated, notably, by Anselm Hollo) in 1962, which included Voznesensky, Yevgenii Yevtushenko, and the lesser known Semyon Kirsanov. While Hollo is justly celebrated as a translator (of William Carlos Williams’s Paterson into German, for one), this is not one of his major efforts, as he himself noted in a post that included this retrospective:

Although I am not well acquainted with Andrei Voznesensky’s entire career, I have just caught up with it on Wikipedia: here. What I generally knew was that he was a semi-official/official poet of the period of liberalization known as “The Thaw,” who served as a poetic ambassador to poets in opposition elsewhere; in the U.S. this would be Allen Ginsberg and Robert Lowell, an American parallel to the unofficial/official faultline of that period. City Lights Books published a “Pocket Poets” mini-anthology titled Red Cats (translated, notably, by Anselm Hollo) in 1962, which included Voznesensky, Yevgenii Yevtushenko, and the lesser known Semyon Kirsanov. While Hollo is justly celebrated as a translator (of William Carlos Williams’s Paterson into German, for one), this is not one of his major efforts, as he himself noted in a post that included this retrospective:

Now long out of print (my present copy is the sixth printing of 1968), it has been an amusing if at times irritating albatross: persons who have never read a line of my own work, or any of my later translations from languages I can truthfully say I’m familiar with . . . have spoken or written to me about the Cats with a nostalgic enthusiasm I find hard to share. With the possible exception of Voznesensky’s “The Big Fire at the Architectural College,” the poems now strike me as simplistic, sentimental, and not a little hypocritical in their post- and sub-Mayakovskian rhetoric. It is also quite obvious that neither I nor any of their subsequent translators have been able to match whatever purely aural pleasures the originals may offer. (Anselm Hollo; here)

The attempt at transposition in the period was, at best, a well-meaning misfire, but it led to a number of optimistic Cold War exchanges. As a student at Berkeley, studying Russian (I actually went farther than Anselm, who admits knowing only the alphabet, though his mother was fluent), I got the sonic register of Voznesensky’s work, on a LP of readings featuring his well-known “Ya Goya” (I am Goya) with its imitation of bells (kolokona), playing it for my class to great effect. Ginsberg maintained a dialogue with Voznesensky, as witness his online archive, and that led in turn to a visit to San Francisco in the milieu of City Lights Books I happened to attend, connecting the dots between sonic sublimity and the soft-spoken man at a literary salon at the home of Margot Patterson Doss (Joanne Kyger was there, along with North Beach types), where I believe he read. That would be the mid 80s, perhaps the 1985 visit recorded on Ginsberg’s page; such an exchange brought international credibility to the Beats and their ambience.

The attempt at transposition in the period was, at best, a well-meaning misfire, but it led to a number of optimistic Cold War exchanges. As a student at Berkeley, studying Russian (I actually went farther than Anselm, who admits knowing only the alphabet, though his mother was fluent), I got the sonic register of Voznesensky’s work, on a LP of readings featuring his well-known “Ya Goya” (I am Goya) with its imitation of bells (kolokona), playing it for my class to great effect. Ginsberg maintained a dialogue with Voznesensky, as witness his online archive, and that led in turn to a visit to San Francisco in the milieu of City Lights Books I happened to attend, connecting the dots between sonic sublimity and the soft-spoken man at a literary salon at the home of Margot Patterson Doss (Joanne Kyger was there, along with North Beach types), where I believe he read. That would be the mid 80s, perhaps the 1985 visit recorded on Ginsberg’s page; such an exchange brought international credibility to the Beats and their ambience.

The exchange continues at our later date, in different politics, with different poetics. For the launch at the Voznesensky Center, Vladimir Feshchenko worked out a selection, including my “Afterword” documenting the history of engagement with Russian poetics, and samples from works, including several of the most difficult. The translators present (Lisa Kheresh, Olga Sokolova, and Feshchenko) were paired with their most difficult assignments, and there was a guest appearance by poet Sergei Biryukov, who read a lyric translation of a work I collaged from Poetry in the Schools writings, to great effect. Here is the playlist, in the order of the YouTube recording above:

Introductions by Tatyana Sokhareva and Vladimir Feshchenko

“Afterword,” trans. Feshchenko

“Coda,” trans. read by Sergei Biryukov

from “Conduct,” trans. Feshchenko

from Under Erasure, trans. Lisa Kheresh

from “Plan B,” trans. Olga Sokolova

questions from the public, moderated by Feshchenko

Despite the striking uniformity that the visionaries of the new culture strove for, the Thaw was inspired by very different sources and was an exceptionally porous time where different ideas about reality could coexist. Along with the new youth, loudly and boldly asserting their vitality in life and art, one could encounter many disappearing, motley types of the past. Thus, Andrei Voznesensky, one of the main Thaw poets, in his rapprochement with Boris Pasternak, felt that he had taken up the baton of the Silver Age. The Thaw synthesized many things in itself, and left many things unexpressed—in particular, spiritual daring, which found no place in the materialistic agenda. But the “Dark Thaw” is a complex phenomenon in which one can find not only the formalist artistic experiments of the beginning of the century, but also a continuation of the tradition of metaphysical adventurism of the earlier era of Romanticism.” (Ivan Yarygin)

Notes and links

T/k