Continuing my work in the archives, I want to locate the shift from a more or less happy recognition of new writing in the late 70s to what can only be called full-fledged reaction by the mid 80s. While the encounter with Duncan over a materialist reading of Zukofsky was a premonition, it was an isolated—if internalized—event. The San Francisco literary avant-gardes—Language writing among others—got a lot good press at their moment of emergence, in a climate of openness that only encouraged their work. The milieu of Left cultural activism—backed up by federal support for alternative publishing through the NEA and community arts jobs via CETA—is readable in the October 1978 cover of the San Francisco Review of Books. The author shot of Kathleen Fraser juxtaposed with Ron Silliman reading Ketjak at Powell and Market Streets goes with the Left agenda: articles on Black power, the nuclear arms race, the Russian revolution, and—the small press. As with the earlier countercultural moment in the 50s/60s, avant-garde writing and small press publishing were seen as part of a cultural politics extending out in all directions. The inky, unpretentious typography of the cover goes along with a baseline populism of multiple agendas. … More

>> Entries <<

March 23, 2020

Entry 40: Isolate Flecks

It is only in isolate flecks that

something

is given offNo one

to witness

and adjust, no one to drive the car—William Carlos Williams

21 March 2020

What I am to think about, in a room with others, is the nature of Zero Hour—our new life. Our colloquy is an opening to that question.

22 March 2020

The poet often sees oneself as an isolato, “a person who is physically or spiritually isolated from others.” We are collectively isolated, as well.

This is the common condition we have sequestered ourselves within. These are the occasions for what I am now writing: here begin.

23 March 2020

Putting on Vivaldi to get the morning started, I recognize the theme music Delta Airlines uses on its transatlantic flights, to CDG, FRA, or AMS.

Homeless panhandler on corner of southbound Lodge offramp and Forrest reaches out without direction as I round the corner, and falls over.

“With history piling up so fast, almost every day is the anniversary of something awful.” Under this rubric I find words I intend to use . . .

24 March 2020

Imagining our isolation through multiple visual maps: blue and gray dots colliding; exponential curves ticking upward; geography filling in at a rate.

The graph of deaths doubling every two days, every three or five days, every ten days—these are abstractions, what do they mean in the event?

Although concern increases with the incidence of disease, the percentage gap in belief stays constant at about 40% between red and blue states.

Am I a nonperson in a mask and hat, or the announcement of a social order to come? The learning curve for what counts as human is constant. … More

December 21, 2019

Entry 39: Ozone Holes

Pleased to learn of publication of my anti-Trump poem “Plan B” in Lana Turner, I took the magazine’s offer of a free download of Lana Turner 11 (the digital version of Lana Turner 12 is not yet out) as an anticipation of things to come. The website also links to Lana Turner 10, where I published a poem written after the 2004 election, “Blue States (After Fearing),” and indeed there is a connection to the present “Plan B,” written in November 2016. (The paywall is still up for Lana Turner 10, and readers should get the entire issue, but I will provide a .pdf of the poem here). In that poem, I tracked the psychological state I was in after the 2004 election—where George W. Bush achieved his first popular majority, thought he had a mandate, had earned capital and was going to spend it by demolishing Social Security, only to fail spectacularly to do so. At the time, my serious interest in the emergence of fascist imaginaries in American democracy began, and I would spend the next dozen years interrogating their present and past history, through my research, teaching, and travels in Germany. “Plan B” is a culmination of this effort, a poem registering the psychological state of the 2016 election through the perversion of public discourse that, in Adorno’s words from The Authoritarian Personality, indicate a “readiness” to accept anti-democratic forms of government. Adorno links these psychological preconditions of “readiness” to an ensemble of personality traits in and as “ideology”: … More

September 14, 2019

Entry 38: > Ekaterina Zakharkiv

I met Moscow poet Ekaterina Zakharkiv in St. Petersburg in November 2016, at “Other Logics of Writing: Arkady Trofimovich Dragomoshchenko at 70,” the Second International Conference on Dragomoshchenko and experimental poetics. Ekaterina was co-winner of the Dragomoshchenko Prize for younger experimental writers, presented at the new Alexandrinsky Theater on the Fontanka in St. Petersburg. Recently we began an exchange on digital poetics from our respective cultural, linguistic, and theoretical perspectives. This is a first attempt to speak of digital/media poetics across two distinct “regions of practice.”

September 12, 2019

Dear Ekaterina—

Hello! You asked about my approach to analyzing the internet poetic discourse.

I’ve cut and pasted your letter as you will see to create conditions for dialogue:

I am a graduate student of the Institute of Linguistics of the Russian Academy of Sciences, so my methodology is only starting to form, in general it may be said that the study is conducted from pragmatic-linguistic positions, in particular—the theory of speech acts, and also the linguistic poetic method.

My own basis in poetics is heavily indebted to the Formalist tradition, especially Shklovsky, Tynjanov, and Jakobson. There is a disconnect between that method—which influenced early Language writing, particularly with Hejinian, Silliman, and Harryman (and was very much in play when we had our “Letnaya Shkola” in Petersburg in 1989)—and the influences of critical theory, cultural studies, and now digital theory. I am trying to work at these intersections while being “language-centered.”

January 21, 2019

Entry 37: The Psychohistorical Absolute

For nearly all our originality comes from the stamp

that time impresses on our sensibility.

—Baudelaire, “The Painter of Modern Life”

My title is an oxymoron, as there is no “absolute” in the process of “psychohistory.” But to recall Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe and Jean-Luc Nancy’s The Literary Absolute, there is a historical relation of the psychohistorical to the emergence of the literary as an unfolding horizon of meaning, which they describe in the use of the romantic fragment in The Athenaeum. That tradition leads to Hegel’s preference for romantic art as best because it is always incomplete, thus demanding completion, and on to the hermeneutics of Hans-Georg Gadamer and the Konstanz School, with Hans-Robert Jauss and Wolfgang Iser. The concept of horizon, which is everywhere in my critical work (and in the title of my UC Berkeley dissertation Horizon Shift), unites an historical openness of interpretation with the ground of the events of psychic history. Today, for instance, is Martin Luther King’s birthday, and in an online post I recalled hearing the news of his death: “I was in sociology class, junior year, UC Berkeley, taught by Robert N. Bellah, when Martin Luther King’s assassination was announced in class—an event that would puncture the world view of liberals like him. He was, however, eloquent in tribute and memorable.” The meaning of that event was both historical and psychic, and it unfolds, for me and arguably all of us, in a horizon at once open and changing. It was, in short, psychohistorical; it remains so, and the way that it does grounds the horizon of its further interpretation.

January 20, 2019

Entry 36: Ashbery Alpha and Omega

Barrett Watten, “Ashbery Alpha and Omega: Presentism, Historicism, and Vice Versa.” Journal of Foreign Languages and Cultures (Changsha, China), no. 3 (2019): 87–93. For pdf, click here.

Abstract: This reading of a single poem from the last collection of verse John Ashbery published before his death in 2017 sees it as an example of a concept of “presentism” that differs from modernist or postmodern accounts of the “present” associated with abstraction or immanence. Rather, Ashbery’s presentism is historical in being based on overlapping and discontinuous linguistic and experiential frames. Ashbery’s poetic use of the content of experience is always mediated through its presentation as information, ranging from high to low values and often employing “low-mimetic,” pop cultural elements. What results is a suspension of certainty in which meaning is structured and informed by its status as information. Thus leaving open questions of knowledge, Ashbery’s poetry does not represent a fully present consciousness but relies on forms of cognition and information processing that are nonconscious, operating in the background and informed by decades of his practice as a poet. A brief comparison with the late paintings of Willem de Kooning, who experienced cognitive disability at the end of his life, points out similar nonconscious forms of cognition such as motor skill and even aesthetic judgment. The reading is thus informed by information theory, cognitive science, and neurophysiology in showing how Ashbery’s late style makes a present that is historical and structured on his entire oeuvre.

Keywords: Poetics, the New York School, information theory, cognitive science, late style

Headnote: This paper was given in a session titled “Social Readings of John Ashbery” at the Louisville Conference for Literature and Culture After 1900, University of Louisville, Feb. 2018. Thanks to Alan Golding and panelists Sandra Simonds and David Kellogg.

Image: detail from John Ashbery, Late for School, c. 1948. Collage, 12 1/2 x 8 inches. From “John Ashbery with Jarrett Earnest,” Brooklyn Rail (3 May 2016); link here.

August 12, 2018

Entry 35: On Bearing an Inscription

Yesterday I joined many millions throughout the history of humanity and submitted to ritual scarification, of my own volition and free will: I got a tattoo, my first after many years of sworn testimony that I would never do so. Like any complex choice, there was a before and an after—I had been visually imagining and verbally debating such a decision for years, months, and days leading up to the act, which took place on August 11, 2018, in the company of two friends, at the hand of Zach Hewitt at Signature Tattoo on Nine Mile Road in Ferndale, Michigan. The consequences of this act after resonate across time, space, and my work as a writer, beginning now. … More

May 6, 2018

Entry 34: Lost America

The question of my relation to the New Americans over the long decades since the ’70s has recently come up. In working through my last post, a response to a review that framed my 2016 book with a retelling of the poetic debacle of 1978, I linked to an essay I published in 2000 (per copyright date; it likely appeared in 2001) that was, at the time, my critical and historical assessment of some of its major figures: Robert Creeley, Edward Dorn, and Robert Duncan. Duncan (1988) and Dorn (1999) had already passed, and I do not think I sent the essay to Creeley, with whom I maintained good relations at the time (Creeley died in 2005). Creeley tended to glaze when I sent him offprints of my critical writing, for instance the essay on “poetic vocabulary” that links Jackson Mac Low and BASIC English, to which he wrote a one-word response: “Impressive.” Only later did I find, via a comment Creeley dropped in conversation and a letter in his Selected Letters, that BASIC English had been an influence on his work, after a high school teacher asked to write an essay using its minimal vocabulary.

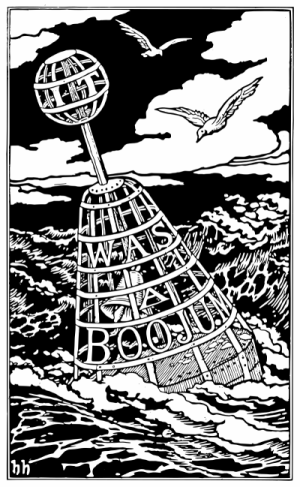

The events of September 2001 decisively changed the focus of thinking through the poetics of the New Americans onto a more immediate political situation; the broad expanses of time needed for genial conversation on poetry and poetics would be displaced by a militarized discourse of threat, reprisal, and nonexistent WMDs. The essay itself was a kind of swerve, using a request from editor Timothy Murphy for a contribution for a volume of the academic journal Genre to be titled “Desert Island Texts,” with a prompt something like, “what one book would you want to have if stranded on a desert island.” … More

May 5, 2018

Entry 33: The Duncan Thing

Grant Jenkins opens his review of Questions of Poetics: Language Writing and Consequences (ALH Online Review, ser. 14:1 [2017]) with an anecdote that has now become canonical lore in American poetry, the encounter between me and Robert Duncan at the San Francisco State Poetry Center’s 1978 Zukofsky memorial. As the story is now forty (4-0) years old, it is more than surprising that it is used to frame a discussion of my 2016 volume of critical poetics, as if no one had ever heard it before:

One of the most infamous events in the history of “postmodern” or “experimental” US poetry is the 1978 argument between Robert Duncan, a veteran of the New American Poetry anthology generation who was 59 at the time, and upstart Barrett Watten, then the 30-year-old self-fashioned cofounder of the more recent school of modernist-inflected verse called “Language poetry.” The incident took place during a film screening at the San Francisco Poetry Center memorializing the “objectivist” poet, Louis Zukofsky, who had recently died at 74. According to most accounts, Duncan interrupted Watten because he did not like the younger poet’s reading of Zukofsky’s poetry.

April 21, 2018

Entry 32: For Kara Walker

Context is everything. To begin with, there is the question of intent in the circulation of racialized images, and the way racism may be ascribed to them. To display racialized imagery in America is to open a Pandora’s Box of every conceivable projection and denial. This is not to separate intention from context, but to find ways of reading it that are contextual and historical. Pandora’s Box is an apt metaphor for the racial content of Kara Walker’s work. There was an incident, about a dozen years ago, when her work was to be first shown at the then-quite-stodgy Detroit Institute of Arts. Think of the recent film Get Out as another of Pandora’s Box—the basement and its horror of substitute body parts. Kara Walker was new to Detroit, and the DIA was still a bastion of cultural separatism in the city. In the film, black bodies are used as vehicles for whiteness that has run out its biological course and needs new life. Off hours, a black janitor encountered the work during installation and complained; the show was cancelled. A state of mind called “the sunken place” is introduced in the film as the horror of racial subjectivity. This is the kind of textbook case that organizations such as the National Coalition Against Censorship deal with all the time, from Huckleberry Finn to the controversy of Vanessa Place tweeting 140-line texts from Gone with the Wind. On the other hand, the contrast between that moment to the ramp up of Kara Walker’s career in museums could not be more marked. The art world itself is represented in the form of a blind gallery owner lusting for authentic talent. … More