Grant Jenkins opens his review of Questions of Poetics: Language Writing and Consequences (ALH Online Review, ser. 14:1 [2017]) with an anecdote that has now become canonical lore in American poetry, the encounter between me and Robert Duncan at the San Francisco State Poetry Center’s 1978 Zukofsky memorial. As the story is now forty (4-0) years old, it is more than surprising that it is used to frame a discussion of my 2016 volume of critical poetics, as if no one had ever heard it before:

One of the most infamous events in the history of “postmodern” or “experimental” US poetry is the 1978 argument between Robert Duncan, a veteran of the New American Poetry anthology generation who was 59 at the time, and upstart Barrett Watten, then the 30-year-old self-fashioned cofounder of the more recent school of modernist-inflected verse called “Language poetry.” The incident took place during a film screening at the San Francisco Poetry Center memorializing the “objectivist” poet, Louis Zukofsky, who had recently died at 74. According to most accounts, Duncan interrupted Watten because he did not like the younger poet’s reading of Zukofsky’s poetry.

This thumbnail, loaded with characterizations like “infamous,” “veteran,” “upstart,” “self-fashioned cofounder,” and most reductive, “modernist-inflected verse called ‘Language poetry,'” has little to do with the content of Questions of Poetics. Jenkins strains to find a footnote relating the event to the narrative construction of The Grand Piano (where it is indeed returned to several times, as a part of a history of the emergence of our school in the late ’70s). There is a discussion of Duncan’s poetry on the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley, as one of four poets who read at Berkeley in the ’60s. In that discussion, I write about the tension between myth and history in Duncan’s work, in fact the subordination of the latter by the former. There, the strife that Duncan theorized is readable in the challenge to poetic “orders” by the eruption of the War and rebellion as spiritual conditions. The “ensoulment” of Duncan’s poetics (see my discussion here) contains the historical and particular.

There is a similar effort at mythopoetic subordination in Jenkins’s review. The event as a crisis in poetry, which is not primarily discussed, is used to frame the historicism and particularity of my six chapters—each focused on different approaches to Language writing as historical, periodized, critical, and theoretical, reading the literary movement not at its outset but through its consequences after 2000. The Hail Mary of returning to 1978 wants to read this account, forty years later, as the work of an “upstart cofounder.” And it’s not as if this event had been not been treated elsewhere; there is an entire chapter in Lisa Jarnot’s Robert Duncan: The Ambassador from Venus (chap. 61). In it, the literary evening is described with the same catastrophic affect as the Jonestown massacre and the Milk/Moscone murders—and there may have been some bleed between associations with those events.

In taking on such “awe-ful” affect, the Duncan/Watten split has now become an object; I will call it “the Duncan Thing”—using the Lacanian/Žižekian sense of “the existence of the void at the centre of that reality called the Thing” (see extended discussion here). For members of the largely homosocial community that supports and reproduces Duncan’s work (present in numbers at last February’s Louisville conference), the absence at the heart of the event becomes an imponderable “object” necessary for the illusion of mythic coherence. As Adorno and Horkheimer theorized in Dialectic of Enlightenment, without sacrificial violence the order of myth falls apart. Two things to note, then, in Jenkins’s use of the event to frame his review of my work: first, there is a sacrifice at the heart of mythic orders that must be returned to for them to continue; and second, those feeding the myth by recurrent sacrifice render themselves subordinate to it. Myth is the violent conservation of hierarchy that founds “community” in this sense, and the nonexistent Thing of the sacrificial act perpetuates it.

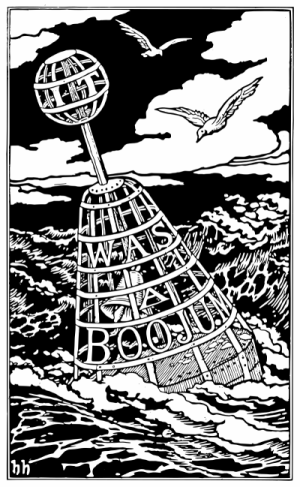

Since the event itself, its reenactment has dogged my life in poetry. It was indeed a faultline that was raised and enforced against Language writing and particularly the political and theoretical claims made for it. Divisions in and among the group occurred as well, against this awe-ful imponderable Thing. To quote Lewis Carroll, “the snark was a boojum, you see!”—the nasty anecdote conceals a deathward element, a void at the heart of poetic community. Language writing came on the scene, precisely, to rescue poetry from myth in the ’70s, and it may be time to revive its anti-mythic politics from a later perspective. It is the regressive return to myth, and its containment of critical poetics, that is a concern at the present time, where mythic thinking and regression have become synonymous.