Continuing my work in the archives, I want to locate the shift from a more or less happy recognition of new writing in the late 70s to what can only be called full-fledged reaction by the mid 80s. While the encounter with Duncan over a materialist reading of Zukofsky was a premonition, it was an isolated—if internalized—event. The San Francisco literary avant-gardes—Language writing among others—got a lot good press at their moment of emergence, in a climate of openness that only encouraged their work. The milieu of Left cultural activism—backed up by federal support for alternative publishing through the NEA and community arts jobs via CETA—is readable in the October 1978 cover of the San Francisco Review of Books. The author shot of Kathleen Fraser juxtaposed with Ron Silliman reading Ketjak at Powell and Market Streets goes with the Left agenda: articles on Black power, the nuclear arms race, the Russian revolution, and—the small press. As with the earlier countercultural moment in the 50s/60s, avant-garde writing and small press publishing were seen as part of a cultural politics extending out in all directions. The inky, unpretentious typography of the cover goes along with a baseline populism of multiple agendas. … More

>> Entries <<

April 6, 2020

Archive 02: Reception Study

Pursuing the truth hidden in the archive, I could have called this entry “Poetry Wars,” as a hot-button topic. But that would be to give in to the facile and fetishistic, the already scripted. What I am interested in is learning from the traces of reception, what the reception of a work, an author, a movement gives us as information, in a kind of feedback loop, of the world in which it was meant to have its effect—to “win its way” as Stein wrote. But that course is never guaranteed. Whitman’s assertion of a reciprocity with the people, his readers—”I alone receive them with a perfect reception and love—and they shall receive me”—may be posited as an ideal that is impossible to achieve. And it is true that the reception history of Language writing often took place in an opposite sense—to the extent that populists could claim it had been rejected by the “people,” seen as a literary ideal. It could be said that the entire movement, as a group form of “negative capability,” held open its horizon of reception until some future time to come. Rather than empowering the reader, Language writing intuited its reception as something it could not yet wholly envision or grasp. The writing itself, I would now say, took form on the basis of an unknown futurity.

Pursuing the truth hidden in the archive, I could have called this entry “Poetry Wars,” as a hot-button topic. But that would be to give in to the facile and fetishistic, the already scripted. What I am interested in is learning from the traces of reception, what the reception of a work, an author, a movement gives us as information, in a kind of feedback loop, of the world in which it was meant to have its effect—to “win its way” as Stein wrote. But that course is never guaranteed. Whitman’s assertion of a reciprocity with the people, his readers—”I alone receive them with a perfect reception and love—and they shall receive me”—may be posited as an ideal that is impossible to achieve. And it is true that the reception history of Language writing often took place in an opposite sense—to the extent that populists could claim it had been rejected by the “people,” seen as a literary ideal. It could be said that the entire movement, as a group form of “negative capability,” held open its horizon of reception until some future time to come. Rather than empowering the reader, Language writing intuited its reception as something it could not yet wholly envision or grasp. The writing itself, I would now say, took form on the basis of an unknown futurity.

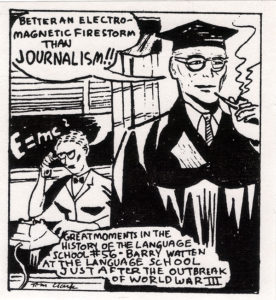

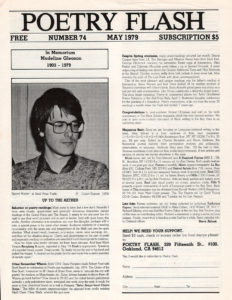

Returning to the files for evidence does not disclose a simple negative history; far from it. “The morning of starting out, so long ago” (Ashbery) was as legitimately optimistic as it could have been. In that sense, an “originary” moment, at least on the West Coast, might not be the December 1978 “canon-making” debate with Duncan over Zukofsky’s reception, but the May 1979 “focus on language-centered writing,” edited by Steve Abbott, in the Bay Area journal Poetry Flash. By that time, L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E had begun its four-year run of publication out of New York, and San Francisco small presses such as The Figures, Tuumba, and This Press had brought some of the early major works of the movement. But seeds of contestation or reaction were already evident. Alan Soldofsky’s “Language and Narcissism”—one of five contributions to the issue—was the first attested moment of “Language baiting,” and tended to overshadow the positive contributions of the forum. From that moment to Tom Clark’s cartoon parody of this author—likely drawn from the head shot on the cover of Poetry Flash—was but a little minute. And from that moment to the present, “forty years on” as Tony Green wrote, the discourse of populist antagonism to Language writing has been in place. Returning to the archive creates a series of talking points to comprehend what was at stake. … More

April 1, 2020

Archive 01: Zukofsky @ SFAI

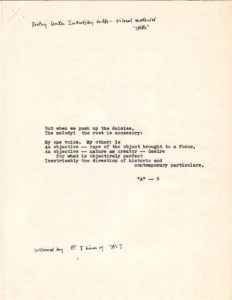

As I work through and with my archive, I want to supplement it online to show some highpoints of what I am finding there. The first in my imagined series, as a kind of originary moment, documents my talk on Louis Zukofsky, or better put the talk I hoped to give on his work, at the San Francisco Art Institute on 8 December 1978, the famous evening with Robert Duncan. This event was a watershed in my poetics; the occasion of the splitting of New American communitas from the social formation of Language Writing that ricocheted widely during the following decades; and the first in the series of literary controversies that have marked my work and career. Most recently, the online journal Dispatches from the Poetry Wars obtained and uploaded the tape of the event—which had been circulating since someone reproduced it without permission from the American Poetry Archive at San Francisco State University. The tape itself became the subject of lore and an object of struggle in its own right—a fusion of material text and mythic correspondence all archivists yearn for. What was missing were the images. [Contd. below]

Zukofsky quotes from “A”

Page 2, the first eight lines of “A”–7, has been lost but is necessary in this sequence.

March 23, 2020

Entry 40: Isolate Flecks

It is only in isolate flecks that

something

is given offNo one

to witness

and adjust, no one to drive the car—William Carlos Williams

21 March 2020

What I am to think about, in a room with others, is the nature of Zero Hour—our new life. Our colloquy is an opening to that question.

22 March 2020

The poet often sees oneself as an isolato, “a person who is physically or spiritually isolated from others.” We are collectively isolated, as well.

This is the common condition we have sequestered ourselves within. These are the occasions for what I am now writing: here begin.

23 March 2020

Putting on Vivaldi to get the morning started, I recognize the theme music Delta Airlines uses on its transatlantic flights, to CDG, FRA, or AMS.

Homeless panhandler on corner of southbound Lodge offramp and Forrest reaches out without direction as I round the corner, and falls over.

“With history piling up so fast, almost every day is the anniversary of something awful.” Under this rubric I find words I intend to use . . .

24 March 2020

Imagining our isolation through multiple visual maps: blue and gray dots colliding; exponential curves ticking upward; geography filling in at a rate.

The graph of deaths doubling every two days, every three or five days, every ten days—these are abstractions, what do they mean in the event?

Although concern increases with the incidence of disease, the percentage gap in belief stays constant at about 40% between red and blue states.

Am I a nonperson in a mask and hat, or the announcement of a social order to come? The learning curve for what counts as human is constant. … More

February 18, 2020

Document 83: @ Louisville

Ahead of our “nonsite” event in Louisville Friday, I wanted to put the record of my contributions to the Louisville Conference up, to point to the critical and poetic work that has scarcely been considered in this instance. Content—not just projection—matters. I have added a sentence or two to each title, along with publication history, to give a sense of what my path through Louisville has been. The Louisville Conference has indeed been important for me, and I am deeply grateful for and committed to it. But I never shouted anyone down at this conference, though I did go on too long a couple of times early on.

Nonsite event

“Cancel Culture as Unfree Speech: Parrhesia @ The Louisville Conference,” independently organized, The Brown Hotel, Louisville, February 2020.

A brutal rationalization takes place in the neoliberal university beyond the wildest dreams of Mario Savio; the degradation of speech we have suffered is its symptomatic manifestation. The university has achieved a condition of unfree speech that has spread, in viral fashion, from the central core of the administration to the department and classroom, each internalizing and performing its version of the paranoia and defensiveness of the larger polity, where it reigns unchecked.

Lectures and panel presentations

“Refunctioning Surrealism: Eugene Lim’s Dear Cyborgs and Karen An-hwei Lee’s Maze of Transparencies,” The Louisville Conference on Literature After 1900, canceled February 2020. … More

January 20, 2020

Document 82: Avant-Garde @ Zero Hour

CALL FOR PAPERS

Avant-Garde @ Zero Hour:

Destruction and New Meaning

“Crisis”: 7th Biennial Conference of the European

Network for Avant-Garde and Modernist Studies

University of Leuven, Belgium

17–19 September 2020

My proposed session(s) stem from on-going work on literary and visual modernism at the “moment” of destruction in 1945: Stunde Null or Zero Hour. I focus on the epochal date of 1945 (Stunde Null or Zero Hour, in its divergent forms across the global territories) as both the end of World War II and an inaugural moment of transition to the global order we now live. For one or more sessions at EAM, I propose to recover and theorize the avant-garde to interpret the “zero hour” of 1945 and explore the historical moment of crisis of 1945—of European destruction, the end of colonial empires, the origins of our global order—as progenitor of new forms of avant-garde writing, visual art, and thinking. I want to access key examples, or a larger overview, of how avant-gardes in Europe, the Americas, and globally gained new impetus from several related projects: overturning the cultural violence of fascism; finding an ethical imperative in “bare life” in the forms of destruction; and resisting recuperation into already existing historical and artistic narratives. What was “new” in 1945 was not “new” in the sense of modernist innovation; rather, it was to see the world as it had never been, as a locus of destruction and creation with historical possibility but also with the undoing of progressive narratives. In this sense 1945 is no longer only an epochal date for the avant-garde per se but a defining moment of modernity, at which its aesthetic, ethical, and historical horizons coincide uniquely. Creation and destruction in modernity at 1945 can be comprehended through the work of a number of avant-garde writers and artists, particularly in their dialectic between “particulars,” unique and intractable values and forms, and “universals,” values and forms as applicable universally, across languages and cultures. Send proposals for interrogating the work of post-1945 avant-gardes, seen in relation to the form of historical crisis of 1945 and its challenge to progressive historicism, by Thursday, January 30, for submission by Saturday, February 1, to:

Barrett Watten, English, Wayne State University

b.watten@wayne.edu or barrett.watten@gmail.com

Image: Eugene Von Bruenchenhein, No. 877, May 30, 1960.

December 21, 2019

Entry 39: Ozone Holes

Pleased to learn of publication of my anti-Trump poem “Plan B” in Lana Turner, I took the magazine’s offer of a free download of Lana Turner 11 (the digital version of Lana Turner 12 is not yet out) as an anticipation of things to come. The website also links to Lana Turner 10, where I published a poem written after the 2004 election, “Blue States (After Fearing),” and indeed there is a connection to the present “Plan B,” written in November 2016. (The paywall is still up for Lana Turner 10, and readers should get the entire issue, but I will provide a .pdf of the poem here). In that poem, I tracked the psychological state I was in after the 2004 election—where George W. Bush achieved his first popular majority, thought he had a mandate, had earned capital and was going to spend it by demolishing Social Security, only to fail spectacularly to do so. At the time, my serious interest in the emergence of fascist imaginaries in American democracy began, and I would spend the next dozen years interrogating their present and past history, through my research, teaching, and travels in Germany. “Plan B” is a culmination of this effort, a poem registering the psychological state of the 2016 election through the perversion of public discourse that, in Adorno’s words from The Authoritarian Personality, indicate a “readiness” to accept anti-democratic forms of government. Adorno links these psychological preconditions of “readiness” to an ensemble of personality traits in and as “ideology”: … More

December 2, 2019

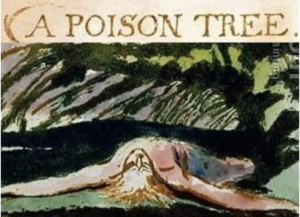

Document 81: An Example

I was angry with my friend;

I told my wrath, my wrath did end.

I was angry with my foe:

I told it not, my wrath did grow. … More

September 14, 2019

Entry 38: > Ekaterina Zakharkiv

I met Moscow poet Ekaterina Zakharkiv in St. Petersburg in November 2016, at “Other Logics of Writing: Arkady Trofimovich Dragomoshchenko at 70,” the Second International Conference on Dragomoshchenko and experimental poetics. Ekaterina was co-winner of the Dragomoshchenko Prize for younger experimental writers, presented at the new Alexandrinsky Theater on the Fontanka in St. Petersburg. Recently we began an exchange on digital poetics from our respective cultural, linguistic, and theoretical perspectives. This is a first attempt to speak of digital/media poetics across two distinct “regions of practice.”

September 12, 2019

Dear Ekaterina—

Hello! You asked about my approach to analyzing the internet poetic discourse.

I’ve cut and pasted your letter as you will see to create conditions for dialogue:

I am a graduate student of the Institute of Linguistics of the Russian Academy of Sciences, so my methodology is only starting to form, in general it may be said that the study is conducted from pragmatic-linguistic positions, in particular—the theory of speech acts, and also the linguistic poetic method.

My own basis in poetics is heavily indebted to the Formalist tradition, especially Shklovsky, Tynjanov, and Jakobson. There is a disconnect between that method—which influenced early Language writing, particularly with Hejinian, Silliman, and Harryman (and was very much in play when we had our “Letnaya Shkola” in Petersburg in 1989)—and the influences of critical theory, cultural studies, and now digital theory. I am trying to work at these intersections while being “language-centered.”

January 21, 2019

Entry 37: The Psychohistorical Absolute

For nearly all our originality comes from the stamp

that time impresses on our sensibility.

—Baudelaire, “The Painter of Modern Life”

My title is an oxymoron, as there is no “absolute” in the process of “psychohistory.” But to recall Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe and Jean-Luc Nancy’s The Literary Absolute, there is a historical relation of the psychohistorical to the emergence of the literary as an unfolding horizon of meaning, which they describe in the use of the romantic fragment in The Athenaeum. That tradition leads to Hegel’s preference for romantic art as best because it is always incomplete, thus demanding completion, and on to the hermeneutics of Hans-Georg Gadamer and the Konstanz School, with Hans-Robert Jauss and Wolfgang Iser. The concept of horizon, which is everywhere in my critical work (and in the title of my UC Berkeley dissertation Horizon Shift), unites an historical openness of interpretation with the ground of the events of psychic history. Today, for instance, is Martin Luther King’s birthday, and in an online post I recalled hearing the news of his death: “I was in sociology class, junior year, UC Berkeley, taught by Robert N. Bellah, when Martin Luther King’s assassination was announced in class—an event that would puncture the world view of liberals like him. He was, however, eloquent in tribute and memorable.” The meaning of that event was both historical and psychic, and it unfolds, for me and arguably all of us, in a horizon at once open and changing. It was, in short, psychohistorical; it remains so, and the way that it does grounds the horizon of its further interpretation.