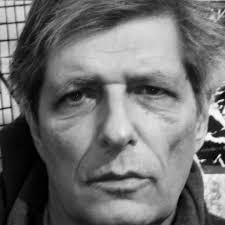

Yesterday I received news that New York poet Lewis Warsh has died. He had been ill, I heard from a distance, and I had sent birthday greetings earlier in the month—unanswered. We had a kind of . . . rivalrous, or contestatory, poetic conversation over the decades, concerning basic issues of what counts as poetry, what the poetic calling is. The issue was person versus language, if a bit characterized and reduced. We go way back. I met Lewis in Albion, California, up the coast in California, the summer of 1972. I had moved there with Sandy Berrigan, David, and Kate, and Lewis visited on his way down to Bolinas, where I would also see him, and later in Stinson Beach, sharing a beach house with the cartoonist Greg Irons. When I assumed full editorship of This in 1973, taking a turn toward more complex aesthetics, he sent me several works, which I have scanned below. He would have sent them from Cambridge, where he lodged briefly after the West Coast. We wrote a collaboration (now in the archive), and he published my autobiographical writings—some exceptionally raw—in the “Autobiography” issue of The World (28), with its larger than life format and cover drawing by Alex Katz, New York School period style for sure. For the issue of This (4), he sent three works (he had a particular way of calling poems “works,” each being unique):

Yesterday I received news that New York poet Lewis Warsh has died. He had been ill, I heard from a distance, and I had sent birthday greetings earlier in the month—unanswered. We had a kind of . . . rivalrous, or contestatory, poetic conversation over the decades, concerning basic issues of what counts as poetry, what the poetic calling is. The issue was person versus language, if a bit characterized and reduced. We go way back. I met Lewis in Albion, California, up the coast in California, the summer of 1972. I had moved there with Sandy Berrigan, David, and Kate, and Lewis visited on his way down to Bolinas, where I would also see him, and later in Stinson Beach, sharing a beach house with the cartoonist Greg Irons. When I assumed full editorship of This in 1973, taking a turn toward more complex aesthetics, he sent me several works, which I have scanned below. He would have sent them from Cambridge, where he lodged briefly after the West Coast. We wrote a collaboration (now in the archive), and he published my autobiographical writings—some exceptionally raw—in the “Autobiography” issue of The World (28), with its larger than life format and cover drawing by Alex Katz, New York School period style for sure. For the issue of This (4), he sent three works (he had a particular way of calling poems “works,” each being unique):

“Cambridge General” would be the hospital, an anonymous building, nothing like art—but the poem is all art. It is about the use of syntax to render the commonplace exceptional, a kind of linguistic drawing technique, sketching in and leaving out. What I was drawn to here was, first, the fractured syntax and lineation—and in that issue I would also publish works by Larry Eigner, Bruce Andrews, and Joanne Kyger, all breaking up continuity and temporality in one way or the other. I would also stick on certain words or phrases, which seems to “pop” with luminosity. The moment that grabbed me most was the sequence “wash in / on rays of gray / flowers, operating / like an assembly / line.” We had an argument, in fact, about the spelling of gray, which I would spell grey—Lewis doubted he could work with someone who spelled it that way. For me, the open ay was too much—tone leading of vowels, setting up consonances like “on rays of gray.” So I would not write like that. But then “rubber / ducks float / on the / lake / when / the swans / charge south,” and I am caught between the grey constructivism of the hospital and assembly line and the pop irony of rubber ducks and home fries, which are absurd. Poets think like that, it is not just about language. Robert Desnos would agree. The poem—you are invited to read on—is like the wedding of Alexander Calder and Fairfield Porter: a mobile of everyday perceptions, on an asymmetrical edge. It was just what I wanted for This, as were the two occasional pieces that followed it. Reading them now brings back a time when catching the light in the optic of the present set words in order and brought them up close:

—16 November 2020