Avant-Gardes @ Zero Hour: European, American, Transnational

Monday, April 5–Wednesday, April 7

A virtual colloquy featuring 16 scholars, writers, artists

& the global premiere of Carla Harryman’s “Occupying

Theodor W. Adorno’s Music and New Music: A Re-Performance”

attendees welcome; registration required; click here

Originally organized for the 2020 conference of the European Network of Avant-Garde and Modernist Studies (EAM) conference in Ghent, Belgium, canceled due to COVID-19 (here), and following last year’s virtual colloquy on “Modernism @ Zero Hour” (here). The seminars have been reorganized and expanded, with participating scholars and artists from seven nationalities and time zones, and with the addition of the streaming of Carla Harryman’s revised production of “Occupying Theodor W. Adorno’s Music and New Music,” originally staged at dOCUMENTA 13 (2012). The colloquy takes up transnational approaches to the emergence of avant-garde art and practices after the metahistorical date of “Zero Hour,” 1945—the end of the war which is not one—to comprehend the profound reflection on destruction, displacement, and a new global order in post–1945 movements and works.

Organized by Barrett Watten, English, Wayne State University

and Lauri Scheyer, British and American Poetry Research Center,

Hunan Normal University

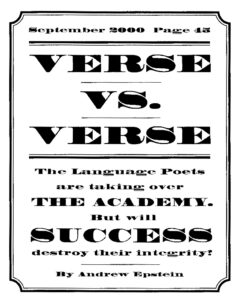

Sponsored by Projects in Poetics and Statement Magazine,

California State University, Los Angeles

… More